Dragon Rules

by Andrew Hall

According to consensus science, ancient cultures across the planet — with no communication between them — independently and spontaneously invented dragons. Remarkably, they all invented the same physical description and modus operandi: a fire breathing serpent, origin in the sea, havoc across the land, and crazy weather. Given the consistencies and global reach of this ancient archetype, a rational thinker might consider some significant global event is behind it, common to each culture. Yet the consensus relegates this to coincidence or a spontaneous glitch in a collective consciousness of which their own science denies the existence.

Truth is, ancient man was intimate with an environment more extreme than we have today and understood it much better than we do. The ancients left us tales, artwork and structures that are more than just breadcrumbs. They are bold, articulate statements about the environment they lived in, and how different it was from ours.

The features examined in this article are proof of the dragon’s passage, not random and coincidental anomalies. They appear predictably, as expected of the circuit.

Action and Reaction

Reactive power is a two way street. Energy is both released and absorbed as current alternates, spitting out and sucking back in. Chapter 7 showed the canyons and river channels arc-blasted by reactive power from resonant discharges. That was an example of reactive power spitting out. When it sucks back in, reactive power creates a mountain, not a canyon.

This is where things get really interesting. The resonant reactive discharge that blasted the river apart, creating a junction, also created mountains on reactive inflow vectors.

The inflow current is backwards relative to reactive outflow. Since there is a bias in the line current, the backwards direction of reactive inflow current produces a different vector sum than the outflow.

The inflow current depletes a region of electrons. This breaks the bonds in crystalline rock, tearing it apart, heating and dissolving it. Chemistry, magnetism, and the Coulomb force compete to rearrange the landscape.

The depleted region forms a mountain as atomic bonds recombine, first forming a rock wall, called a dyke. The dyke forms where a filament of current begins to steal electrons from the surroundings, pulling material to the filament and pinching it, magnetically. After a discharge neutralizes the current, the material cools, recombines and solidifies into a wall of rock. Wind then piles dust onto the dyke, aided by rarefaction from shock waves and electrostatic attraction to the still depleted zone, building a mountain.

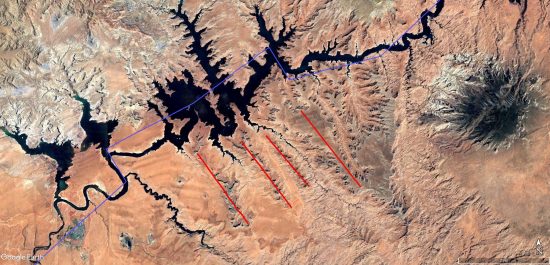

The effect can be seen in this image of the Will Henry and its tributaries where they branch from the Colorado River. Adjacent to the capacitive discharge there are linear mountains (red lines) radiating away from the crux of the river branching. These are the reactive inflow currents, where charge depletion made a dyke on which a mountain formed from windblown dust. These are at angles that increase between the second and third bifurcations, from 40- to 50-degrees with respect to the outgoing inductive current, because these currents are flowing backwards with respect to the line current, and the positive bias inline current increases as reactive power is drawn away in successive discharges, which widens this angle.

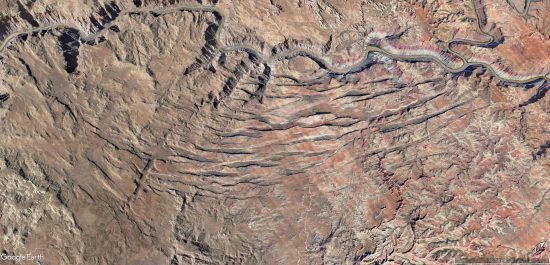

Since there is an inductive, reactive inflow current, there must also be capacitive, reactive inflow currents. And indeed there are. In the first image, the linear mountains were inductive reactive inflow currents. The next image shows linear mountains aligned parallel with supply current just before these same junctions. The parallel mountains are the capacitive reactive inflow currents.

Recall from Part 7, these junctions are caused by resonant frequency that acts like a stopper in the current flow, forcing it to squirt out sideways in reactive discharge. As the line current is slowed by the rising frequency, charge builds in the nose of the current channel, just like pressure builds behind a bottleneck. A far-field positive charge builds parallel and adjacent to the charge building in the line due to capacitance. This is known as “stray capacitance” in the electronics world and is generally something designed out of a system because it creates unwanted harmonic feedback.

It’s parallel to the supply current because it’s actually making a capacitor at some distance defined by the magnetic field, which helps induce currents to build the capacitor’s charge. It’s to the right of the line current because of the “right-hand-rule”, which says the magnetic field is penetrating the ground at these places and saturating it with induced currents.

These capacitors are filaments of positive charge that build-up before the line current explodes in reactive discharge. When the discharge occurs, the capacitive, reactive branch connects with the capacitor filaments and drains them, which has the effect of building a dyke and hence a mountain, from a depleted charge zone.

Once the connection is made and the filaments drained, the capacitive, reactive discharge current is free to turn its vector east to align with the electric field. In all, there are nine resonant frequency bifurcations (marked in green on the accompanying image) along the Colorado and its primary tributaries, including Lake Powell, which is a staccato series of resonant discharges.

Each has the same crab-claw shape with accompanying inflow current generated mountains, inductive outflow currents that vector north, and capacitive outflow currents that vector east, parallel to the line current, which is aligned to the electric field.

You may also note some of these bifurcations are where dams are built, including Hoover, Parker, and Glen Canyon. It’s no coincidence that the bottleneck of a resonant, reactive discharge creates a bottleneck canyon with an arc-blasted basin behind, perfectly suitable for damming. The rocky choke-point is a result of induced reactive inflow currents aimed at the crux of the resonant discharge.

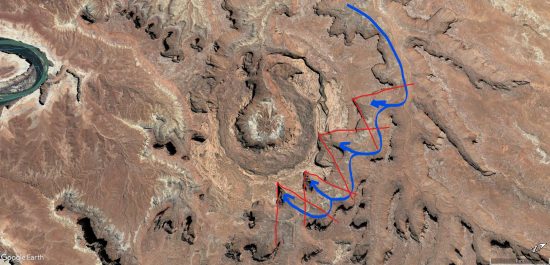

The next image shows line current and outflow reactance in blue and inflow reactance in red for the major resonant discharge bifurcations along the southern portion of the Colorado and Gila.

at each resonant discharge.

In some conditions, mesas are created by reactive inflow instead of mountains. This occurs when the de-saturated zones left by inflow currents leave mesa’s behind as landscape around is sputtered away. In the next image of Lake Powell, there are inductive absorption currents 180-degrees opposed to the inductive, reactive power discharges. See Sputtering Canyons — Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 for some background on sputtering. Note the fine tendrils running parallel around and between the highlighted mesas. These canyons are scars from tendrils of charge that shot through this area, electrifying an aquifer, or wet layer of deposits and causing the land to sputter away from that layer, leaving already de-saturated areas behind.

Another example of this is at the Green River branching. South of the junction is an arcing network of filamented canyons and mesas parallel to incoming line current, just before the bifurcation. This is another area where capacitive, reactive charge built parallel to line current prior to the resonant discharge bifurcation.

Charge built in the ground and then was drawn away by three large short-circuiting filaments (three canyons perpendicular to the river at top center in the image) that shoot from the line current orthogonally through the arc, zig-zagging to touch each filament. This left depleted ground where the linear mesas are, while the canyons were excavated by sputtering.

Two things can be said about these reactive discharges:

First, the current of electrons and negative ions in the discharge — the “dragon’s blood”, so to speak — is a destructive force that excavates the land in explosive arc-blast events. The reactive inflow currents, however, are constructive and build mountains and mesas. One is the inverse of the other. It’s interesting to see how complex number math actually displays itself in Nature.

Second, the reactive inflow currents are slow and cold. They diffuse through the land, changing the chemistry and reforming rock over some time, not at the lightning pace of a spark.

Take another look at the Google Earth image where the resonant discharges are highlighted in green. There are other features marked with yellow triangles and red circles. Let’s take a look at those.

Wye Junctions

Refer to the yellow triangles on the image. Not all junctions occur as a result of resonant frequency. Some junctions occur as a result of sudden grounding. As the mainline current climbs the plateau, it’s encountering hot, dry deposits of sand over sheets of water. Aquifers are layered below, left from past tsunami’s, rain, or ancient lakes.

The grounding of the discharge happens when the supply line current induces parallel current in the aquifer and they connect, likely at a spring or other feature that provides continuity between the surface and the aquifer. The sudden grounding creates a new current vector.

As supply line current encounters a conductive path to the ground potential in the aquifer, the supply line voltage is affected. The supply line voltage vector remains straight, and a new line-to-ground voltage vector branches away. It basically creates a kink in the electric field expressed in two dimensions on the plane of the Earth’s surface, but it really results from an interference pattern in the three dimensional, multi-phase electromagnetic field.

A line-to-ground current splits away with this voltage, which is clocked 30- degrees counterclockwise to line voltage in a balanced 3-phase circuit. In a balanced 3-phase circuit, the currents would form a star pattern with 120- degrees between each arm forming what is called a “grounded Wye connection.”

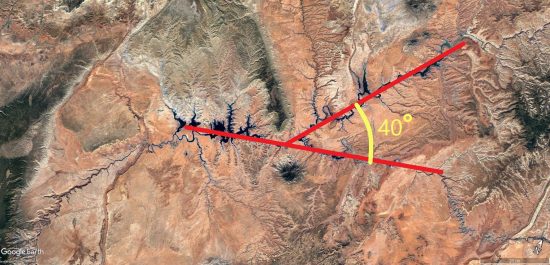

DC bias and a very dirty signal to the current close the current angle down to the 40- and 60-degree angles seen at the Green and San Juan junctions. The vectors represent Nature finding its own balance.

Another clue to its formation is the fact supply line current vector remains straight while the tributary forks away counter-clockwise, but there is no opposing capacitive, reactive discharge evident radiating from the center of the branch, nor is there evidence of reactive inflow currents. These junctions are not due to resonant frequency and reactive power but to an instability in the electric field created by a sudden grounding.

The effect is to bifurcate the dragon. It takes energy from the ground connection to clone itself, and the clone takes a new current vector.

Wye connections are used for various reasons in high voltage transmission, one being to join three-phased circuits with ground. Grounding the connection allows certain harmonic frequencies, called third-order harmonics, to bleed away without interfering and unbalancing the primary phases. In particular, lightning surges will pass to ground without surging the primary circuits.

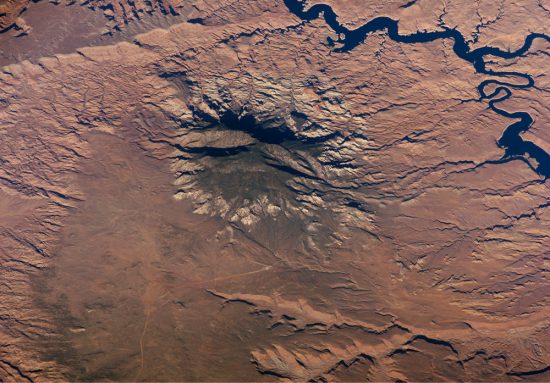

Navajo mountain sits next to the San Juan Junction. It is a fulgurite created by negative cloud-to-ground lightning. It looks very suspicious sitting next to the bifurcation, but it’s not yet apparent if it had a role in creating the bifurcation, or if it was a consequence. There are striations between the river and the mountain, running parallel to the river’s course, indicating capacitive stresses in this region.

A Dragon Runs Through It

One thing that’s quite obvious in the canyonlands of Utah, at the heart of the charged capacitor dome, is the rivers meander wildly, yet they keep true to trajectories along the electric field.

Oscillations in current phase and magnetic fields cause the filaments to wobble and curly-cue. When the branches are in-phase they try to close together on a common, transient current vector, but then push apart when out-of-phase and return to the original line current vector.

In the image below are highlighted areas of extreme current bending and inductive discharges that flare from the bends in flame-like patterns, creating fractal chaos between and around the Green and Colorado rivers near the junction.

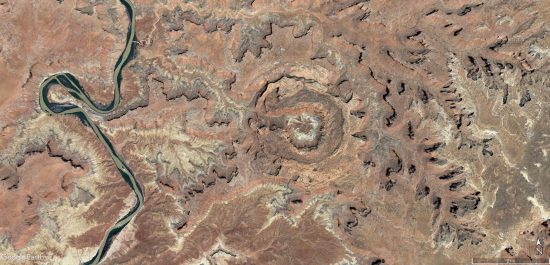

Magnetic fields pulsate and wrestling the currents back-and-forth and create ring currents like the amazing Upheaval Dome — a ring current stuck in its own magnetic field which created an induction coil. The induction coil generated a tightly wound, supersonic, plasma tornado.

The center of the ring current is a clump of sharply pointed tetrahedrons aimed skyward from shock waves where the coil’s induction drew the central, supersonic updraft.

The surrounding rim-rock on the right side of the dome is cut by parallel, triangular bites, adjacent to scalloped walls on the opposing side of the canyon wall farther to the right. This displays the channels of a multiple vortex wind where the tornado’s inflow bent into the central updraft of the induction coil. The triangular bites are from standing shock waves where the wind turned into the updraft of the coil. The scallops display the eddy of multiple vortex jet-streams as they make this turn.

The Hall Effect

Returning to the annotated image of the Colorado system, there are two red ovals indicated. The ovals indicate massive downdraft craters caused by the two main coronal loops on the Colorado Plateau — the San Rafael/Capitol Reef dome and crater complex, and the Monument Valley/San Juan dome and crater complex.

Recall from Eye of the Storm — Part 3, these dome and crater pairs were caused by coronal storms which left immense tetrahedral monoclines where the wind deflected abruptly, creating shock waves. The wind’s deflection was due to the magnetic field pinching around the updrafts and downdrafts.

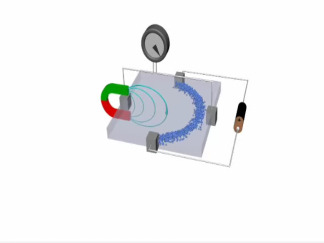

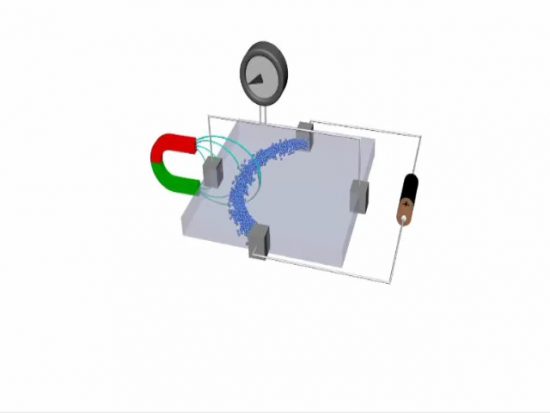

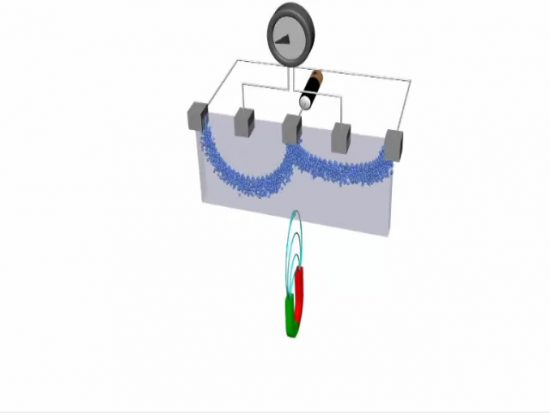

The same magnetic field also redirected the ground-to-ground line currents — the “dragon’s blood”, so to speak — due to the Hall Effect. The Hall Effect basically says a magnetic field will either push or pull a current’s direction depending on polarity. You can see the effect in these diagrams, where an electric current, shown in blue, is either pushed away or attracted to a magnet in close proximity.

Because these regions of high electric flux generated strong magnetic fields around them, especially at the interface of ground and sky, it pushed the arc around negative craters and drew it through positive domes. You can see the San Juan River bend around the downdraft crater, circled in red, and shoot through the center of the updraft dome, shown in green.

and circles downdraft crater, red.

Similarly, the San Rafael updraft dome has tributaries of the Green River shooting through its center, and the downdraft crater is avoided by the arc of Green River and its tributaries.

Another example of the Hall Effect is displayed in these images of the famous “Gila Bend” in the Gila River. Note how the river bends south and then returns to it’s original trajectory as if it’s detouring around an obstacle. It actually is. The current is detouring around the Sentinal-Arlington Volcanic Field, the magnetic field which pushes the current around due to the Hall Effect.

A similar effect happens in the Grand Canyon, but in this case the river detours to the south twice below the Uinkaret Volcanic Field. There is a distinct, straight segment between the two detours.

The bar in the center is possibly a function of the frequency of the alternating current and the discharge velocity as it advances. In other words, the current is pushed away from the volcano while in opposing phase and pulled back towards the volcano as phase rotates, then pushed away again as phase completes a rotation.

Or it could be an artifact of the way the circuit connects with the volcano subsurface, where it can’t be seen, producing an effect similar to the diagram.

“X” Marks the Spot

The final feature to examine is related to the resonant discharge we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, only this type of discharge occurs in the middle of the line current. In other words, the resonant discharges we previously discussed were at the head of the dragon, as it searched its way along the electric field. These reactive discharges shot out of the body of the dragon due to pulsations in the flow of current.

The “dragon” at this point is a thousand miles long. The longest recorded lightning strike is only two hundred miles in length. So this is very big lightning. As discharges occur, pulses of energy and bolides of densely charged matter shoot up and down the line current.

When two waves of charge density collide, they interfere, causing a momentary spike in energy similar to a rogue wave, or the pressure waves in water pipes that cause hammer and cavitation. A reactive discharge results creating box canyons to either side rotated roughly 90-degrees to the line current and forming a cross. The reactive discharges are always a proper 180-degrees opposed, and occasionally one of the tendrils will continue to be induced, generally north to form a longer canyon. The Grand Canyon especially exhibits these types of reactive discharge.

Eye of the Storm — Part 9 will complete the description of the Parallel RLC circuit that created the Colorado River, and then describe circuits beneath the crust from which the dragon emerged.

Additional Resources by Andrew Hall:

YouTube Playlists through 4-2022:

Andrew Hall — EU Geology and Weather

Andrew Hall — Eye of the Storm Episodes (13)

Surface Conductive Faults | Thunderblog

Arc Blast — Part One | Thunderblog

Arc Blast — Part Two | Thunderblog

Arc Blast — Part Three | Thunderblog

The Maars of Pinacate, Part One | Thunderblog

The Maars of Pinacate, Part Two | Thunderblog

Nature’s Electrode | Thunderblog

The Summer Thermopile | Thunderblog

Tornado — The Electric Model | Thunderblog

Lightning-Scarred Earth, Part 1 | Thunderblog

Lightning-Scarred Earth, Part 2 | Thunderblog

Sputtering Canyons, Part 1 | Thunderblog

Sputtering Canyons, Part 2 | Thunderblog

Sputtering Canyons, Part 3 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 1 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 2 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 3 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 4 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 5 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 6 | Thunderblog

Eye of the Storm, Part 7 | Thunderblog

Andrew Hall is a natural philosopher, engineer, and writer. A graduate of the University of Arizona’s Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering College, he spent thirty years in the energy industry. He has designed, consulted, managed, and directed the construction and operation of over two and a half gigawatts of power generation and transmission, including solar, gasification, and natural gas power systems. From his home in Arizona, he explores the mountains, canyons, volcanoes, and deserts of the American Southwest to understand and rewrite an interpretation of Earth’s form in its proper electrical context. Andrew was a speaker at EU2016, EU2017 and the EUUK2019 conferences. He can be reached at hallad1257@gmail.com or thedailyplasma.blog

Disclosure: The proposed theories are the sole ideas of the author, as a result of observation, experience in shock and hydrodynamic effects, and deductive reasoning. The author makes no claims that this method is the only way mountains or other geological features are created.

The ideas expressed in Thunderblogs do not necessarily express the views of T-Bolts Group Inc. or The Thunderbolts Project.