Apr 5, 2019

Astronomical phenomena are better understood using an electrical perspective.

Previous Pictures of the Day reported that there are twin lobes of gamma rays extending beyond the Milky Way’s core. The formations are about 65,000 light-years in diameter, and are thought to indicate that Birkeland currents are creating z-pinches in the galactic plasmas. Intense electromagnetic fields in those filamentary structures accelerate electrons to velocities that approach light speed. Those rapidly moving electrons emit synchrotron radiation, the principle source for gamma-rays in space.

Some celestial objects shine so brightly that they are considered by astronomers to be the most intense energy sources in the Universe. Phenomena like quasars, Gamma-ray Bursters (GRB), Fast Radio Bursters (FRB), and blitzars are among those mysteriously powerful entities. The latter three are short-lived, however. The problems with GRBs are addressed in other Pictures of the Day, but how they are generated is not known.

Quasars, or, quasi-stellar radio sources, shine with a continuous output. Astronomer Maarten Schmidt identified the first radio quasar, 3C 273, in 1963. However, there was a problem with his observation: its radio wave spectrum was anomalous—he could not identify which elements created the Fraunhofer lines that he saw. He then concluded that they were actually hydrogen gas absorption lines that were red-shifted. Consensus theory says that an object with such a high red shift is billions of light-years away, so it must be brighter than a million galaxies.

Since all of those violent radiation sources are detected through the use of redshift theory, such bizarre “explanations” are necessary, in order to keep alive the idea that Doppler-shifted Fraunhofer lines can be used as a convenient yard stick.

According to a recent press release, supermassive black holes promote the accumulation of interstellar material. Those particles are compressed and heated by the black hole’s gravity until they shine in the high frequency electromagnetic spectrum, often emitting gamma-rays. Jets from the superheated gas and dust that are aligned with Earth are called blazars, “…and in a flare they can emit as much radiation as a million billion suns.”

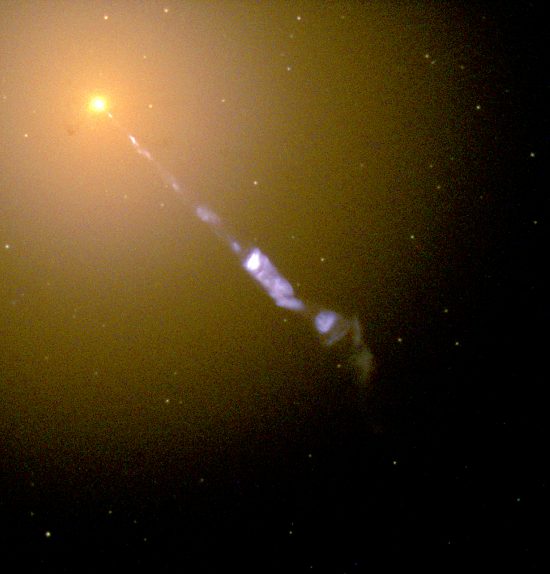

Blazars and quasars are both active galaxy nuclei (AGN), thought to be supermassive black holes with accretion disks and plasma jets (electrons) perpendicular to the accretion disk. As mentioned, astronomers think that blazars are more powerful and more variable than quasars, because they see their plasma jets head on. Quasar jets, on the other hand, are viewed at an angle.

One of the mysterious factors about blazars is how electrons in the jets achieve such high velocities. The research team believes that the “fire hose” jets are propelled by “winding up” a black hole’s magnetic field so tightly that electrons “crash into” photons, stimulating the emission of gamma-rays and causing the radiation to become polarized. Why do the gamma-rays come from a point that is thousands of light-years away from the putative black hole’s accretion disk? They do not know.

Laboratory experiments reveal that the easiest way to accelerate electrons to high velocity is in an electric field. Electric charge flow in plasma generates electromagnetic fields that constrict the current channel. Electric filaments remain coherent over long distances and can transmit power through space. Those filaments are the jets seen in galaxies and stars, with concentrations of energy at various points.

Synchrotron radiation is emitted by the constricted elements in Birkeland currents, and it is that radiation that is mistaken for gamma-rays, X-rays, and extreme ultraviolet light along the lengths of blazar jets. If redshift is not a viable theory, then quasars and blazars are not “billions of light-years” away, so are most likely not so powerful. If they are local to the Milky Way, then they should be re-evaluated in light of electrical theories.

Stephen Smith