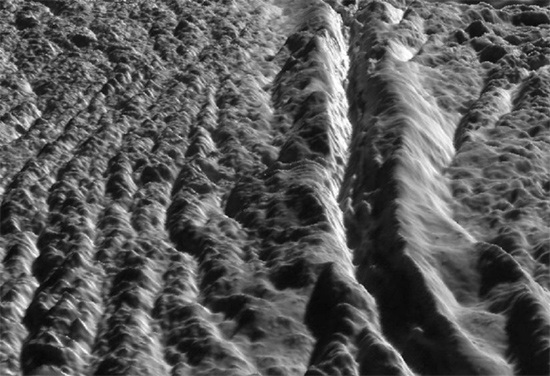

“Tiger stripes” in Damascus Sulcus, Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Universities Space Research Association/Lunar & Planetary Institute.

Oct 02, 2014

Enceladus continues to confirm the electrical nature of its topography.

Saturn’s moons are difficult to categorize, let alone explain. As previous Picture of the Day articles point out, they vary in composition, orbital inclination, size, and mass. With 61 moons now identified, Saturn appears more like a miniature Solar System with its own influences apart from the Sun.

Enceladus takes its name from Greek mythology. The son of Ouranos, he was one of the Gigantes, or Titans, who were overthrown by Zeus and his minions. It is perhaps an ironic name, since it is a tiny world only 494 kilometers in diameter. Its gravitational acceleration is about 1% of Earth’s 1g field, so a long jump by Carl Lewis might conceivably put him into a low orbit, provided there could be some way for him to survive a temperature of -201 Celsius (and the vacuum). Enceladus was discovered by William Herschel in 1789.

Past Picture of the Day articles have proposed that the serpentine trenches, cut like swirling ribbons across the surface, are not due to the tidal stresses from Saturn’s gravity, but probably result from crawling discharges of electric current. The so-called “tiger stripe” terrain, out of which jet plumes of warm water vapor, are most likely manifesting a weaker version of the massive electrical activity that once carved and punctured Enceladus with magnetically confined plasma beams.

The consensus opinion from planetary scientists is that the tiger stripe features are most likely caused by “shear heating” as lateral faults in the crust are set in motion by Saturn. Water vapor escapes the cracks and is dissociated by the intense environment, whereupon it flows along the flux tube connections with Saturn, injecting immense clouds of charged particles into its plasmasphere.

It is not our contention that the large formations on Enceladus are being actively cut and distorted today. It is possible that they are the remains of the aforementioned massive plasma discharges from Saturn or the proximity of some other charged object that at some time in the past initiated the circuit. Today, the remnant electric fields are continuing to modify Enceladus with “dark mode” discharges, but the effect is less dramatic.

Electric arcs can produce braided rope-like trenches when plasma filaments move across a surface. Gouges can be created without the lateral surface movement required by fracturing. Do the images transmitted from the Cassini-Equinox spacecraft reveal any lateral displacement? Can fracturing experiments in any laboratory on Earth form the braided seams on the surface of Enceladus?

In the image at the top of the page, the main channel is bordered by ridges that rise to 150 meters. The central culvert is 250 meters deep. These are relatively large structures, considering the small size of the moon. It is easiest to get an idea of what is happening on Enceladus by comparing it to another moon in the Solar System: Europa.

Although the plumes on Enceladus are comparable to another of Jupiter’s Galilean moons Io, with its traveling “volcanic caldera,” the dual-ridge faults, the supposed subsurface ocean of liquid water, and the broad, smooth valleys make it more like Io’s bigger sister.

Some rilles on Europa are 70 kilometers wide and travel 3000 kilometers through the landscape—almost 30% of its equatorial distance. The rilles have parallel sides and a constant width over their length. As with Enceladus, it was suggested by the Galileo spacecraft’s mission specialists that tidal forces are responsible for them. However, tides, acting on the moon’s irregular surface, would not be able to maintain a uniform displacement over that distance.

Interestingly, the Europa team referred to it as having “a surface that looked as if it had been clawed by a tiger with talons several kilometers wide.” Both worlds, described in similar fashion, demonstrate the effect of “surface lightning” as it rips great furrows for hundreds of kilometers, throwing out material to either side.

Electric currents below the surface would have caused electromagnetic induction heating, thus accounting for the ice rafts on Europa. The same phenomenon could have also affected Enceladus, bringing about warmer areas in and around the tiger stripes, along with the dark current disintegration of the ice into water vapor.

Stephen Smith

Click here for a Spanish translation