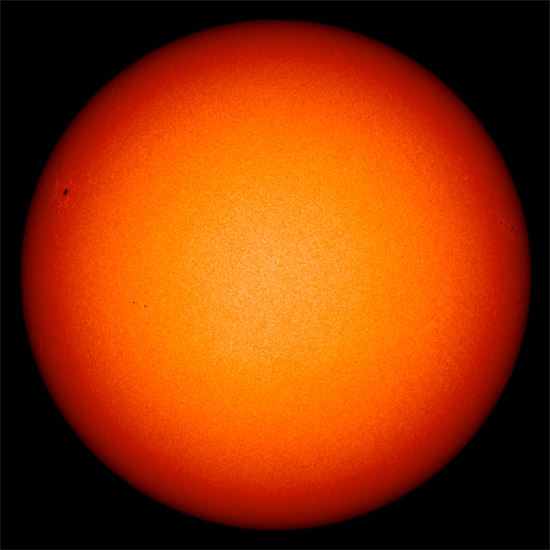

Latest image of the quiet Sun from the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) satellite (March 25, 2013). Credit: ESA/NASA

Sep 05, 2013

The Sun is not a fusion reactor.

In a recent Picture of the Day, it was noted that sunspots are not well understood by astronomers. Furthermore, their bizarre electromagnetic displays are not readily explainable by models of solar activity that rely on radiant emissions from thermonuclear energy. The Sun demonstrates that electrical and magnetic properties dominate its behavior.

Almost 70 years ago, Dr. C. E. R. Bruce offered a new hypothesis about the Sun. Being an electrical researcher, as well as an astronomer, Bruce proposed that the Sun was a discharge phenomenon:

“It is not coincidence that the photosphere has the appearance, the temperature and spectrum of an electric arc; it has arc characteristics because it is an electric arc, or a large number of arcs in parallel. These arcs quickly result in the neutralization of the accumulated space charge in their neighbourhood and go out. They are not therefore stable discharges, but may rather be looked upon as transient sparks. Arcs thus continually appear and disappear. It is this coming and going which accounts for the observed granulation of the solar surface.” (A New Approach in Astrophysics and Cosmogony By C. E. R. Bruce)

Years later, in 1972, the late Ralph Juergens wrote a series of articles suggesting that the Sun is not an isolated body, but is the most electrically active object in the solar system—the focus of a radial electric field extending outward almost to the next star system. Juergens was the first one to link electricity in the Solar System to the galactic circuit and to theorize that the Sun might have an external power source.

In the electric Sun hypothesis, the Sun is an anode, or positively charged terminal. As previously mentioned, the cathode is an invisible “virtual cathode,” called the heliopause, at the farthest limit of the Sun’s coronal discharge, millions of kilometers from its surface. This is the double layer that isolates the Sun’s plasma cell from the galactic plasma that surrounds it.

In the Electric Universe model, the voltage difference between the Sun and the galaxy occurs across the heliopause boundary sheath. Inside the heliopause the weak, constant electric field centered on the Sun is enough to power the solar discharge. The visible component of the glow discharge occurs above the solar surface in layers.

In the chromosphere, at 500 kilometers above the surface, the coldest temperature exists: 4400 Kelvin. At the top of the chromosphere, 2200 kilometers up, the temperature rises to about 20,000 Kelvin. It then jumps by hundreds of thousands of Kelvin, slowly continuing to rise, eventually reaching 2 million Kelvin in the corona. The Sun’s reverse temperature gradient agrees with the glow discharge model, but contradicts the idea of nuclear fusion.

The discovery that a “solar wind” escapes the Sun at between 400 and 700 kilometers per second was a surprise for the nuclear theory. In a gravity-driven Universe, the Sun’s heat and radiation pressure are insufficient to explain how the particles of the solar wind accelerate past Venus, Earth and the rest of the planets. Since they are not rocket-powered particles, no one expected such acceleration.

According to the Electric Sun theory, an electric field focused on the Sun causes the radial movement of charged particles: the greater their acceleration, the stronger the field. A positive space-charge sheath nearest the anode (Sun) accelerates positive ions, principally protons, to form the solar wind. But as noted, the interplanetary electric field is extremely weak. No spacecraft has been designed to measure the voltage differential across 100 meters, but the solar wind does confirm the Sun’s e-field, sufficient to sustain a drift current across the Solar System. Within the heliospheric volume, the implied current is sufficient to power the Sun.

Stephen Smith