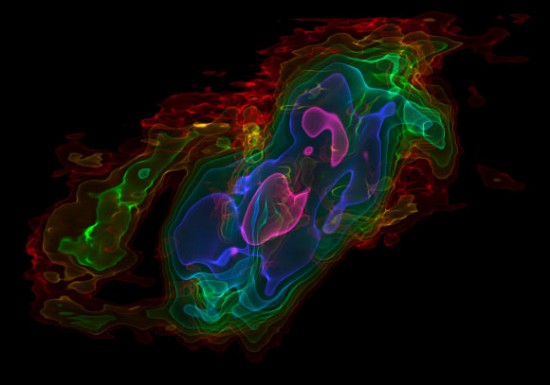

This picture shows a view of a three-dimensional visualisation of ALMA observations of cold carbon monoxide gas in the nearby starburst galaxy NGC 253 (The Sculptor Galaxy). The vertical axis shows velocity and the horizontal axis the position across the central part of the galaxy. The colours represent the intensity of the emission detected by ALMA, with pink being the strongest and red the weakest. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Erik Rosolowsky

Original Post September 20, 2013

The large ALMA radio telescope in Chile has discovered that “billowing columns” of “gas” are “fleeing” from gravitational forces that would snare them into new stars. The size of the Sculptor Galaxy depends on the outcome.

Unless, of course, star formation is not so much a matter of gas and mass and it is a function of current density and plasma. In the Electric Universe, the pinching force from a Birkeland current pulls in nearby matter and squeezes it into a denser thread-like filament. This is what happens in the discharge channel of a lightning bolt.

At a galactic scale, the interstellar “lightning” would take thousands, perhaps millions, of years to run its course. It could even be part of a persistent circuit. Fluctuations and instabilities in the channel form double layers, kinks, and cells, some of which are further pinched into stars. Studying the distribution of “gas,” or of “plasma” for that matter, gives little predictive basis for calculating the number of stars that might be generated.

Alberto Bolatto, the lead author of the paper that announced the finding, said, “[W]e can clearly see for the first time massive concentrations of cold gas being jettisoned by expanding shells of intense pressure created by young stars. The amount of gas we measure gives us very good evidence that some growing galaxies spew out more gas than they take in.”

Dr. Bolatto seems not to have had his tongue in his cheek when he made this pronouncement, although it would have been wise to place it there. What “we can clearly see” is a computer translation of radio signals into an image programmed for human interpretation. The “gas” was not so much “measured” as calculated from many assumptions and a few observations. Science is never as clear as press releases make it out to be.

Attributing “expanding shells” to “pressure created by young stars” belies the unquestioned assumptions already undermined by calling plasma “gas.” Rigorous science would require that the question “What else could it be?” be kept in the back of the mind. With plasma, the first assumption would be “expanding cells” created by “electromagnetic forces in current loops.” A stellar counterpart would be coronal mass ejections.

A co-author of the paper, Fabian Walter, notes that the cold gas “is almost perfectly aligned with the edges of the previously observed hot, ionised gas outflow.” Hot, ionized gas flowing in the same “billow” with cold neutral gas must make the laws of thermodynamics squirm. Are the people who deny “charge separation in space” proposing some kind of “thermal separation in space”?

Recognizing that the mixture is plasma resolves the conundrum: Hannes Alfvén, a renowned experimental plasma engineer [he rejected the moniker of “scientist”], repeatedly warned scientists that their simplistic models of plasma were in error. In real plasma, “[t]he electron temperature was often found to be one or two orders of magnitude larger than the gas temperature, with the ion temperature intermediate.”

The electric field that is aligned with the magnetic field—the defining characteristic of a Birkeland current—accelerates electrons more than protons and both more than neutral atoms. (In conventional theory, particle velocities, even when due to electrical forces, are commonly converted to temperatures, as though they were caused by collisions.) Electrons spiral in the magnetic field and emit synchrotron radiation. X-ray observations of the “billows” will likely reveal the presence of ultra-hot electrons.

Electric fields are almost impossible to detect without sending a probe through them. Magnetic fields are much easier to detect. A magnetic map of the Sculptor Galaxy should reveal magnetic fields aligned with these billows.

Mel Acheson