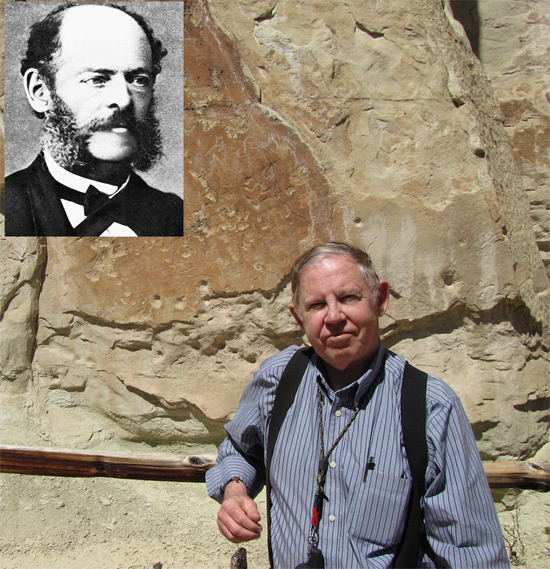

Dr. Anthony Peratt with (inset) Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola

Original Post February 2, 2012

History repeats itself – and that includes the history of science.

Back in 1879, the very notion of ‘prehistoric cave art’ was unheard of. The famous Palaeolithic art galleries inside such caves as at Altamira, Trois Frères and Lascaux still lay undiscovered in the womb of the earth. Enter the Spanish gentleman, jurist and amateur archaeologist, Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola (1831-1888). De Sautuola owned the land in which the cave of Altamira was found in 1868 and began exploring the caves in 1875. In 1879, a chance discovery revealed the marvellous images to the world – while Marcelino was digging in the cave floor, searching for prehistoric tools of the type he had examined at the Paris Exhibition a year before, his daughter Maria, still a child, was “running about in the cavern and playing about here and there” when, suddenly, she “made out forms and figures on the roof”. Her eyes were the first in more than 10,000 years to perceive the cluster of great polychrome bison on the ceiling.

De Sautuola instantly sensed the antiquity of this parietal art. In the following year, his careful conclusions received instant acclaim when a professor from Madrid, Juan Vilanova y Piera (1821-1893), checked out the site, lectured on the discovery, including at the International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology in Lisbon, and inspired crowds of people to visit – among them king Alfonso XII. Clearly, de Sautuola had ushered in a new era in archaeology.

Or had he? Professor Vilanova y Piera was a geologist and palaeontologist, while the enthusiastic members of the public were lay people. Specialists in the archaeological community painted a very different picture of de Sautuola. In the words of Paul Bahn and Jean Vertut, two modern writers:

“One would think that such a remarkable find, albeit unprecedented and unexpected, would have met with interest – even excitement – …; that there would have been a stampede of specialists to see the site; that Sanz de Sautuola would have been fêted and congratulated. It is to archaeology’s undying shame that the very opposite occurred, and that it helped to bring about his premature death in 1888, a sad and disillusioned man still under suspicion of fraud or naivety, with his discovery rejected by most prehistorians. He had taken the hostility personally, as an attack on his honour and his honesty.”

The French élite of archaeologists at that time treated de Sautuola’s proposition with extreme contempt. At the great Congress in Lisbon, a doyen, Émile Cartailhac (1845-1921), walked out in disgust upon de Sautuola’s exhibition of drawings of the Altamira figures, suggesting afterwards that the painted animals were anatomically incorrect. Amid universal rejection in the wake of this conference, the only known person to conduct a personal inspection of Altamira was once again not an archaeologist: even so, the French engineer, Edouard Harlé (1850-1922), apparently had already made up his mind regarding the recent manufacture of the paintings prior to his visit in 1881. The paint was too well preserved.

Eventually, the well-credentialled naysayers had to cave in. With the discovery of additional cave paintings at La Mouthe, Dordogne, in 1895, followed by a steady stream of others, de Sautuola’s name simply had to be inscribed in the annals of archaeology. In 1902, Cartailhac finally cleared de Sautuola of all blame, commenting later that ‘we were blinded by some dangerous spirit of dogmatism’.

Fast forward a century or so and another amateur archaeologist and lover of hiking is seen engrossed in a systematic exploration of prehistoric rock art, from caves to exposed rocks, working in ever greater circles from the direct surroundings of his home. Although most of the logged sites still carry Spanish names, New Mexico is now the centre of action. Amassing what is arguably the largest database of petroglyph and pictograph images worldwide, this collector makes another discovery that should rock the academic world. This time, the thought revolution does not concern the exquisite naturalistic art of Palaeolithic times, but the crude and angular images produced in the Neolithic – and some time afterwards. A mixed group of electrical engineers and mythologists are quick to offer support and spread the word to a sympathetic audience. Fully aware of the importance of his findings and with an unwavering zest for knowledge, the researcher unabashedly lectures at a prestigious university to an audience of archaeologists and other specialists. But he is greeted with derision. A decade on, not a single archaeological publication has addressed his work, not a single archaeologist has picked up the gauntlet and gone out to test the new idea. A stunning silence is the collective voice of scholarship.

Sadly, de Sautuola did not live to see the public vindication of his work. The joy to see his premonitions corroborated by the discovery of countless similar caves was not granted to him. Accelerated by the acrimonious reception of his disclosures, his premature death preceded Cartailhac’s apology by a full 14 years. To fear a similar fate for that second pioneer, doctor Anthony Peratt, is not rocket science – it is rock science.

Rens Van der Sluijs

Books by Rens Van Der Sluijs: