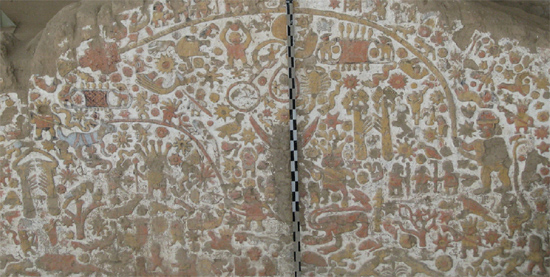

Was this congeries of pictures from the Moche culture of Peru a star map? Lower terrace reliefs, north facade, ceremonial plaza, Huaca de Luna, Valle de Moche, Trujillo, Peru. © Rens Van Der Sluijs

Original Post February 6, 2012

Where does the idea of constellations come from? And how do these arbitrary groups of stars relate to mythology?

The early 20th century saw the ascendancy of a short-lived movement in scholarship called ‘Pan-Babylonianism’, soon bemoaned for its folly. Supporters of this group held that the Babylonians had been remarkably bright astronomers from a very early time onward, spreading their science and the associated mythology to all the world’s major civilisations. Part of this knowledge gift were the notion of constellations, even the zodiac itself, and an understanding of the precession of the equinoxes. The figurehead of the movement, Alfred Jeremias (1864-1935), pontificated that attestations of the zodiac traced back to the Age of Taurus, i. e., the late 5th millennium BCE.

Dotty ideas such as these continued to produce ripples in other areas, such as anthropology and the history of religions, until the present day. Did countless myths worldwide originally encode the precession of the equinoxes, the protagonists representing asterisms? An affirmative ‘yes’ was publicised in such influential bestsellers as Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend’s Hamlet’s Mill (1969), Thomas Worthen’s The Myth of Replacement (1991) and Elizabeth and Paul Barber’s When They Severed Earth from Sky (2006).

Variants of the precessional theory of myth continue to be placed in the spotlights, yet it is incumbent to put their supporters quite firmly on the spot – this line of thought is in as poor a shape as Pan-Babylonianism ever was. Not a scintilla of proof was found for knowledge of precession antedating Hipparchus. Evidence for constellations in Mesopotamia is non-existent prior to circa 2,000 BCE. And specialists agree that the zodiac itself, in its traditional form, only arose in Babylon during the 5th century BCE, affecting the Greek-speaking and the Egyptian worlds as late as the Hellenistic period.

If key myths were not modelled on star patterns, where do familiar denizens of the sky – such as Capricorn, the Twins, the Virgin or the Bear – come from? Were ancient stargazers, prone to an overactive imagination, simply seeing things? Three steps point the way to a satisfactory answer.

The first point is that mental images of these entities must have existed before they were artificially ‘read into’ the starry sky. An English solicitor and amateur orientalist, Robert Brown junior (1844-1912), published a detailed study of the origins of the constellations in 1900. Though his analysis was far from stellar, it was surely spot on with the words:

‘… the great majority of the primitive constellation-figures had a pre-constellational history; and were in fact forms and phases of thought familiar to the mind of early man before he had entered upon the task of stellar uranography … for, as we have seen all along, and as even a cursory examination of the starry heavens will convince any reasonable person, the stars themselves, with certain exceptions which will be noticed, do not in their natural configuration resemble the forms in which they have been grouped, or where there may be a slight resemblance it is equally shared by a hundred other objects which have never been constellation-figures … Having already certain fixed ideas and figures in his mind, the constellation-framer, when he came to his task, applied his figures to the stars and the stars to his figures as harmoniously as possible. Thus, nearly each primitive constellation-figure is a reduplication of an idea connected with simpler natural phenomena, solar, lunar, or as the case may be’.

In the case of Taurus, for example, bulls appeared in iconography from a very early date, but nothing suggests that the corresponding constellation of later times was intended.

A second pointer, of universal application, is that the characters associated with many constellations figure in mythology. The fact is somewhat obscured in Greek astronomy, as most of the classical asterisms were imported from the Near East. Nevertheless, one cannot fail to spot the link between the constellations of Hercules, Andromeda, Hydra or Perseus with the mythical entities of the same names. Countless other one-to-one connections were in circulation. Some would identify Aquarius with Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha, survivors of the deluge; others would pinpoint Auriga as the tragic Phaethon, close to Eridanus, the river in which he drowned.

To complete the picture, a final element is the remarkable pan-human belief, seldom documented, that the stars are mythical beings – such as gods, heroes or ancestors – who were translated to the heavens long ago. Just to give a flavour of this widespread theme of catasterism, the Skidí Pawnee (Nebraska) ‘believed that the stars were either gods or people who had once lived on earth and had been changed into stars at death’. Among the Lillooet (Fraser River, British Columbia), ‘All the heavenly bodies are said to have been people who were transformed during the early ages of the world’. The Khasia (currently Bangladesh) relay that ‘the stars are men who have climbed into heaven by a tree’. Again: ‘All over Australia, it is believed that the stars and planets were once men, women and animals in Creation Times, who flew up to the sky as a result of some mishap on earth and took refuge there in their present form.’ And among the Khoi-San peoples (southwestern Africa), too, ‘the stars are held to have once been animals or people of the Earthly Race, on some cases people who had been transformed upon breaking some taboo’.

Rens Van der Sluijs

Books by Rens Van Der Sluijs: