Apr 22, 2019

Are new moons hiding in Saturn’s rings?

“We must believe then, that as from hence we see Saturn and Jupiter; if we were in either of the Two, we should discover a great many Worlds which we perceive not; and that the Universe extends so in infinitum.”

—Cyrano de Bergerac

As mentioned in a recent Picture of the Day, Cassini is now defunct. It was incinerated by friction with Saturn’s cloud tops, preventing it from going out of control when its maneuvering fuel was exhausted. Mission control managers were concerned that it might crash into one of the many moons around Saturn.

Cassini entered orbit on July 1, 2004. On August 11, 2009 the spacecraft observed the planet’s equinox, when its rings turned edge-on to the Sun, something that happens every 15 years. The then named Cassini-Equinox mission found several anomalous structures buried in the rings, some rising as high as four kilometers. The rings were thought to be only about twenty meters thick, so meta-stable shapes of that size were a complete surprise.

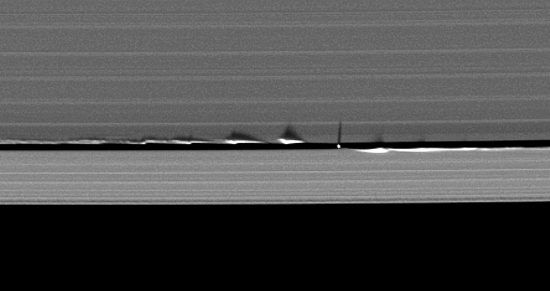

Other shapes were also found embedded in Saturn’s A ring. In the image at the top of the page, an artifact was described by NASA as a “new moon” in the process of emerging from the rings. Planetary scientists think that Saturn’s icy moons were formed in the remote past, when it possessed a larger, more robust ring system. According to astrophysicists, its moons formed near the edge of those massive rings and then moved away into individual orbits. That process is thought to have “depleted” ice and rocks from the larger rings, to the point where moons can no longer form. The discovery of dense “clumps” Is mysterious to consensus ideas.

Conventional theories of Solar System formation propose that the infant Sun was surrounded by a disk of material out of which the planets and planetoids condensed. Saturn is seen as a kind of “Solar System in miniature”, so what happens there is often forced onto unknown conditions in the past.

This is not the fist time that a small object, believed to be another moonlet, has been seen in Saturn’s rings. In July 2009, Cassini photographed an ice ball, this time in Saturn’s B ring. It was identified because it cast a long shadow across the ring plane during equinox, when the angle of the Sun was ideal. Known as S/2009 S1, it is a mere 400 meters in diameter.

How do clumps of ice and the ridges form in the rings? It is conventionally assumed that collisions and shock waves initiate the necessary resonant vibrations for material to gather together. Gravitational attraction from so-called “shepherd moons” is said to be an additional source of influence. Small moons, such as Daphnis, do move up and down through the ring plane, affecting the motion of ring particles.

However, a far stronger force than gravity is neglected in their speculations: Saturn’s rings and moons are electrically charged objects moving within its vast plasmasphere. It is those electric fields, and attractive/repulsive qualities, that are most likely creating the instabilities that contribute to the formation of “moonlets”. Clumping is far more likely to occur in charged material.

Stephen Smith