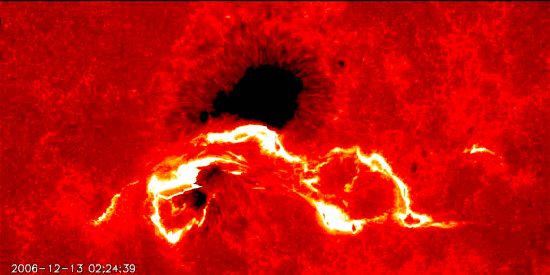

The Sun was quiet from 2008 to 2010, so sunspots like this one disappeared. Credit: the Hinode Mission.

Apr 11, 2018

Sunspots are poorly understood.

“High noon, I can’t believe my eyes,

Wind is ragin’, there’s a fire in the sky.

Ground shakin’, everything comin’ loose,

Run like a coward but it ain’t no use.

Edge of the river, it’s an ugly scene,

People gettin’ pushed, people gettin’ mean.

The change is comin’ and it’s gettin’ late,

Ain’t no survivin’, and there ain’t no escape.”

— Change in the Weather by John Fogerty

Sunspots and solar flares result from changes in electrical energy. The Sun resides in a “bubble” of positive charge with respect to the interstellar medium (ISM), so it probably experiences cyclic influences from changes in its galactic circuit. Based on some extreme phenomena, such as coronal mass ejections, that circuit includes influences extending over thousands of cubic light-years. The power moving through those “cosmic transmission lines” is not known, but consensus astronomers are constantly amazed by solar flare output.

The Sun fluctuates in strength and visible sunspots in a 22 year cycle. During the past 11 or 12 years, the Sun remained relatively spot-free past its predicted time. That quiet period ended when a large solar flare erupted in February 2014. It then returned to a more inactive state.

Electric Universe advocate, Wal Thornhill wrote:

“The standard thermonuclear star theory has no coherent explanation for the approximately eleven-year sunspot cycle. In the electrical model the sunspot cycle is induced by fluctuations in the DC power supply from the local arm of our galaxy, the Milky Way, as the varying current density and magnetic fields of huge Birkeland current filaments slowly rotate past our solar system.”

As written many times in the past, Electric Star theory sees the Sun is an anode, or positively charged terminal, whose heliospheric boundary is an electric double layer that isolates it from galactic plasmas flowing through the ISM. Since voltage differences occur within the heliosphere, the Sun probably experiences a charge/discharge phenomenon. It is the Sun’s capacitive, resistive and inductive behavior that drives its activity and not thermonuclear explosions.

As mentioned, the Sun is entering what should be a quiet phase. However, in early September 2017 the Sun erupted with several powerful solar flares. Solar flares are classified according to their X-ray output: C-class flares possess X-ray measurements in the 10^-6 watts per square meter range (W/m^2), while X-class flares can exceed 10^-4 W/m^2. On September 6, 2017 the Sun exploded with an X2.2 and then an X9.3 flare, after unleashing several less powerful events earlier in the week. The X9.3 incident was the eighth largest solar flare ever recorded.

Solar flares are composed of charged particles, since they follow Earth’s polar electromagnetic cusps. Their power can be illustrated by a September 7, 2005 X17 solar flare that impacted Earth’s magnetosphere, knocking out radio transmissions and overloading power station transformers. Is it a coincidence that hurricanes Katrina (August 29, 2005) and Rita (September 23, 2005) occurred on either side of the fourth largest X-flare ever recorded?

A previous Picture of the Day reported that, 12 years later, hurricanes Harvey (August 17, 2017) and Irma (August 30, 2017), with the highest wind speeds of any Atlantic hurricane, were spawned during a time when the eighth largest solar flare ever recorded erupted from the Sun. At similar points in the solar cycle, within days of each other, violent electromagnetic changes in the Sun initiated violent weather events on Earth.

The smoothed sunspot number peaked in April of 2014 and has been declining ever since. The current prediction is that this will be the least active solar minimum since Cycle 14, in February of 1906.

Stephen Smith