Aug 25, 2017

Why are stars most often seen in pairs?

More than half of all stars observed in the Milky Way have one or more companions, suggesting that something, at least in our galaxy, influences the formation of multiple star systems. Stars are so remote from each other that those distances are sometimes illustrated by two gnats flying around in the Grand Canyon. It is, therefore, unlikely that binary stars are due to gravitational attraction.

On March 7, 2009 NASA launched the Kepler Space Telescope on a planet hunting mission. As written in a previous Picture of the Day, Kepler does not use Doppler shift to detect stellar “wobbles” from orbiting planets, it uses a photometer. Astronomers believe that objects passing in front of stars will dim their light by a tiny fraction, so Kepler was designed to monitor stars in the 0.430 to 0.890 micron wavelengths, otherwise known as the visible light spectrum.

One of Kepler’s potential discoveries is that many planets are incredibly hot—hotter than their parent stars. This is a mystery to astrophysicists, since they are too hot to be planets and too small to be stars. For example, KOI 74b was measured at 39,000 Celsius, while the star it orbits is 9400 Celsius. Consensus theories cannot explain why the “planet” is hotter than a star. KOI 74b is thought to be about as large as Jupiter, so, according to conventional understanding, it is far too small for thermonuclear fusion. Kepler 38b is another strange object, possibly about as large as Neptune, except that its temperature measurement is close to 15,000 Celsius. It is also so close to its star that it revolves in only five days.

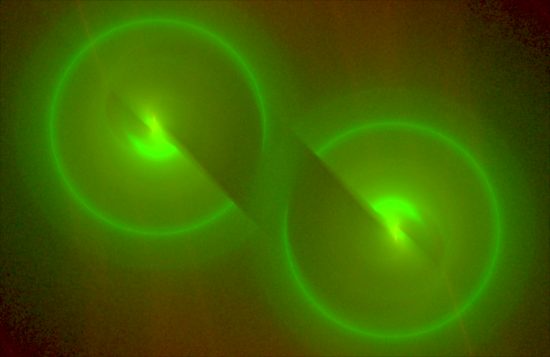

In an Electric Universe, such bizarre conditions could be explained by electrical fissioning. Since a star’s electrical stress is focused on the surface, if the flux differential becomes too intense, due to variability in its power supply from the galaxy, it might split into two stars. The surface area of two stars is able to accept more electrical stress.

According to a recent press release, astronomers studying Kepler data announced that they are getting a handle on how binary star systems form. Most binaries are thought to evolve from “dust cores”, otherwise known as “proplyds” (PROto-PLanetarY Disk), where gravity is said to pull wispy gases together until they reach pressures sufficient to ignite thermonuclear fusion. The research team believe that that all stars “…form in widely separated binary pair systems, but that most of these break apart either due to ejection or to the core itself breaking apart.” Some are so gravitationally locked, however, that those dusty aggregations are “… likely to be the birthplace of two stars…” so there are, “… probably twice as many stars being formed per core than is generally believed.”

How stars are born and evolve must include the most prevalent condition in the Universe: plasma. Electric star theory proposes that stars are born when electric charge flow is confined into filaments that wind around each other, forming z-pinches. Laboratory experiments reveal that those regions are where star formation is likely to occur, instead of through the eighteenth century Nebular Hypothesis, upon which mainstream proposals rely.

New stars are unstable because of their extreme electrical environments, so, as mentioned, they tend to split into one or more daughter stars, equalizing their electrical potential. That explains why most stars are binary.

Planets form when surface electric discharges synthesize heavier elements from primordial hydrogen and helium. Those heavier elements build-up inside stellar interiors until they reach a critical threshold, which releases excess mass in the form of highly ionized gas giant planets, along with smaller, denser rocky bodies. That explains the strange, hot planets in fast, close orbits around their parent stars.

Stephen Smith