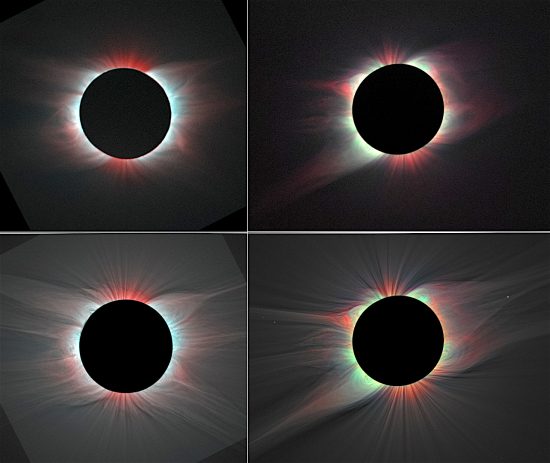

The solar corona. Red indicates ionized iron at .79 microns wavelength, blue represents ionized iron at 1.07 microns, and green shows iron at .53 microns. Credit: Habbal, et al.

Jun 21, 2017

Why is the Sun’s corona so hot?

“It has gradually come to be acknowledged that aurora and magnetic perturbations should be regarded as rather moderate manifestations—at present the only ones there for us to observe—of an unknown cosmic agent of solar origin, and quite different from light, heat or gravitation.”

— Kristian Birkeland

On August 21, 2017 there will be a total eclipse of the Sun visible from many regions of the United States. One of the Sun’s most mysterious features, the corona, should be visible to the naked eye during the event, as the image at the top of the page illustrates.

What is the corona, and why is it so puzzling to heliophysicists? From an Electric Universe perspective, the confusion arises because consensus theories maintain that the corona, as well as all other aspects of the Sun, is generated by kinetic effects: gigantic “acoustical wave guides”, known as magnetic flux tubes, are said to channel solar energy from the Sun’s interior out into space. There is also said to be a vast “conveyor belt”, dragging solar matter down into magnetically active zones deep inside the solar interior, where it is “reenergized.” The thinking is that sunspot magnetic fields decay, allowing the conveyor belt to pull what is left of them back inside the Sun.

Most research groups studying the Sun mention magnetic fields, but they fail to include the “electro” in those reports—they are electromagnetic fields. As anyone involved with Electric Universe theory knows, there is no way to generate a magnetic field without electricity.

The Electronic Sun theory points out that coronal heating, along with other solar phenomena, is due to changes in its electrical supply. Since the Sun is externally powered there is no need to resort to an outmoded theory of internal fusion reactions. Instead, Birkeland current filaments carry electricity through the Milky Way, supplying the Sun with variable power. Rather than an electrostatic model, an electrodynamic model involving plasma discharges can best describe solar activity.

Laboratory experiments, initially conducted by Kristian Birkeland, revealed that a plasma torus forms around an electrically energized sphere, creating discharges between the sphere’s middle and lower latitudes. Those discharges are called “spicules”, also called “anode tufts”, and are an effect expected from a positively charged Sun.

Spicules rise thousands of kilometers above the Sun’s photosphere, carrying ionized plasmas with them. This idea leads to a simple explanation for the corona’s greater than 2 million Kelvin temperature: positive ions collide with ions and neutral atoms in that location.

As retired Professor of Electrical Engineering, Dr. Donald Scott wrote:

“When these rapidly traveling +ions pass beyond the reach of the intense outwardly directed E-field force that has been accelerating them, they…are moving much faster…Because of their high kinetic energy, any collisions they have at this point with other ions or neutral atoms are violent. This creates high-amplitude random motions, thereby “re-thermalizing” all ions and atoms in this region…to a much higher temperature.”

Stephen Smith