Nov 29, 2016

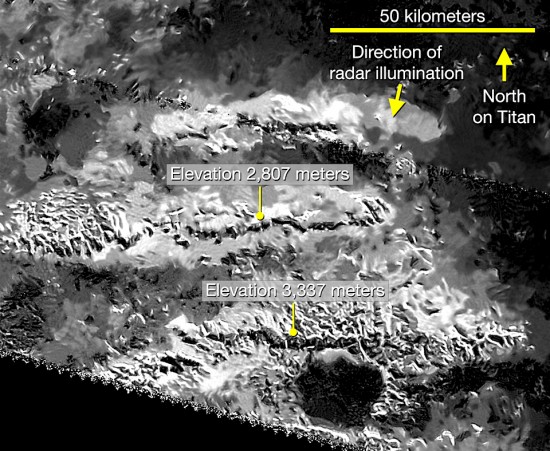

The tallest mountain on Titan.

The Cassini spacecraft was launched October 15, 1997 on a mission to explore Saturn and Titan, the gas giant’s largest moon. With the Huygens lander included, Cassini was the largest interplanetary space probe ever launched. It is 6.7 meters high, four meters wide and weighed 5712 kilograms on launch day. Cassini entered orbit around Saturn on June 30, 2004.

On December 24, 2004, the Huygens lander separated from Cassini and began a twenty-day journey to Titan, reaching a speed of nearly 20,000 kilometers per hour relative to the surface of the moon. The first pictures from Huygens revealed a surface covered with pebbles.

Titan is the fifth largest rocky body in the Solar System, with a diameter of 5150 kilometers. It is larger than Mercury (4878 kilometers), the Moon (3474 kilometers) and Pluto (2274 kilometers). Of all the planetary moons, only Ganymede is larger than Titan, with a mean diameter of 5262 kilometers, just 112 kilometers difference. What makes Titan stand out from the rest is that it has an atmosphere, something which Ganymede does not possess, although Ganymede has an intrinsic magnetic field, which Titan does not have.

Recently, data from Cassini provided topographic information identifying Titan’s tallest mountain, Titan Mons, at 3337 meters within the Mithrim Montes region. Stephen Wall, from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory said: “It’s not only the highest point we’ve found so far on Titan, but we think it’s the highest point we’re likely to find.”

An interesting aspect to the discovery is that most of Titan’s tall peaks are on the equator. Previous observations of Xanadu reveal other mountains of similar height. Since Titan is mountainous, researchers think that some kind of tectonic activity is taking place “…related to Titan’s rotation, tidal forces from Saturn or cooling of the crust…” as the press release states.

Since astrophysicists are prone to explain the Solar System by comparing it to Earth-based processes, “interior” forces are thought to be responsible for most features on Titan, as well as erosion to sculpt them. Most mainstream scientists involved with investigating Saturn and its moons believe that there is methane rain on Titan, along with oceans of liquid ethane. Previous Picture of the Day articles take issue with that theory, however.

When Cassini found that Titan is rapidly losing its atmospheric methane, conventional theorists had to come up with some mechanism that would have replenished the loss over billions of years. One of the first proposals was that Titan is covered with oceans that evaporate fast enough to compensate for atmospheric loss. However, Huygens found no evidence for such oceans. Then the discovery of a “domed feature” suggested a solution: Perhaps it was a “cryovolcano”, an eruption of a nearly frozen mixture of ammonia, water, methane and other hydrocarbons. Such eruptions from a hidden interior source of unknown extent would provide methane in amounts that could be adjusted to match the measured loss. Those eruptions might also contribute to mountain-building.

This kind of insistence on preconceived beliefs identifies a theory in extremis. Planetary scientists “explain away” anomalous observations that are contrary to entailments of the theory rather than confront the necessity for a new theory.

The Electric Universe proposes a more general and more straightforward explanation: Titan is a “young” celestial body and has not yet reached equilibrium.

When gas giant planets experience episodes of electrical “overstress”, they might expel smaller and more-condensed lumps of matter—the rocky planets and moons. Over a relatively short time, the electrical interactions tend to transfer energy among the planets and moons so that their interactions are minimized. This results in a distribution of orbits that, to gravity-only theories, appears to have been stable for eons. In this view, many of the anomalous observations of the planets are understandable as direct consequences of the electrical theory, without the theory having to be adjusted case-by-case.

Ancient records indicate that Saturn underwent electrical fissioning events, with the possibility that Titan was expelled during those events (Saturn’s rings are also remnants). The newly minted moon was positively charged with respect to the new environment outside Saturn, so it experienced intense electrical activity after it was ejected. Electric arcs raised anode blisters, called fulgamites. Close inspection of the structures on Titan will most likely find that they have more in common with fulgamites than with tectonic activity on a dead, frozen world.

Among the principle tenets of Electric Universe theory is that the Solar System was the scene of catastrophic encounters between charged planetary bodies at sometime in the recent past. Electric fields interacted with clouds of plasma, causing major disruptions in orbits and geological stability among the planets and moons. Indeed, new objects may have been added to the mix in the form of comets, scaling down in size from things as big as Venus and Titan, to particles small enough to make up Saturn’s rings.

Stephen Smith