Oct 23, 2015

Flying through a vapor plume from an ice moon.

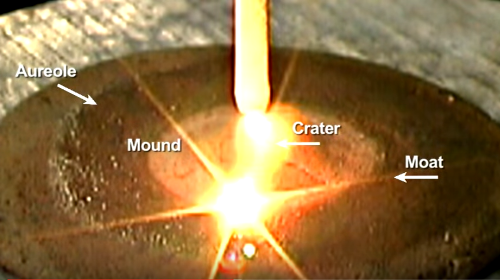

The Cassini spacecraft is preparing to fly by Saturn’s moon Enceladus on October 28, 2015 when it will pass though the mysterious plume of gas and water vapor erupting from the moon’s south polar region. At that time, Cassini will be as close as 49 kilometers, traveling at a speed of 30,600 kilometers per hour relative to Enceladus.

Recently, Cassini achieved a view of the moon’s north pole that has not been seen before. The Saturnian system’s orientation to the Sun, combined with Cassini’s orbit around Saturn, made it impossible to fly to such high latitudes. Images reveal that a massive system of cracks, extending all the way around the moon, also crosses both poles. In some cases the cracks split craters in half. Anaglyph images show cracks that are “steep and deep”, with nearly vertical sidewalls: Baghdad Sulcus, for example.

Some images suggest a surprising aspect to the cracks, they are chains of craters. There are too few sharply focused close-ups to be absolutely sure but, many Pictures of the Day portray similar cracks and canyons on moons and planets that are crater chains, so the presumption is not unwarranted. Electrical activity in the recent past, along with a continuous charged particle bombardment from Saturn is the reason that crater chains affect how Enceladus is interpreted.

The consensus view is one of friction and gravity. Enceladus is thought to be “kneaded” by Saturn’s immense gravity in the form of tidal action: variations in its orbit mean that Enceladus is squeezed and pulled in Saturn’s gravitational grip. That force causes its internal structure to stretch and compress, creating heat enough for a liquid ocean to exist more than 15 kilometers beneath the ice. This idea has taken hold so strongly that one press headline read:

“Enceladus’ jets reach all the way to its sea.”

Enceladus is a small moon, only 494 kilometers in diameter. Its surface is so cold that no chemistry can occur, so planetary scientists hope that its “briny ocean” will provide a reason to fund more missions. One idea, similar to that which has been suggested for Jupiter’s moon Europa, is to send a lander with the ability to melt its way down to the water.

Oceans of water notwithstanding, an August 11, 2008 flyby of Enceladus found ion and electron beams propagating from Saturn’s northern hemisphere. They were considered puzzling until it was discovered that time-variable emissions from Enceladus’ south polar vents matched-up with the auroral footprint’s brightness variations on Saturn. Several of Saturn’s moons eject charged particles along field-aligned electric currents that contribute to the ring system, as well as auroral activity in its magnetosphere. Enceladus is among them.

NASA’s expectation is that this next flyby in late October will settle the question of a definite connection between the two phenomena. Electric Universe advocates assume that the results will confirm electrical exchanges between Saturn and Enceladus. Cassini’s last close flyby will be at a distance of 4,999 kilometers on December 19, 2015 and will try to determine how much heat is coming from the moon’s interior.

Stephen Smith