Sep 14, 2015

Recent data suggests large amounts of water ice beneath the surface.

No other celestial body is so extensively studied as Mars. The primary goal of robotic wanderers on its surface, as well as “eyes in the sky” from satellite observatories, is to provide data for the “search for life”. Identifying sources of water in the Solar System is considered a necessity if life is to be found anywhere apart from Earth.

Since water sustains the ecology on Earth, it is presumed that water is essential for the establishment and the continuance of life elsewhere. The primary mission of imaging systems, such as the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRise), for example, is to look for evidence that water exists in the open or to confirm that it once existed on the surface. It is hoped that research experiments will find subterranean water or frozen blocks of ice in areas that are shielded from direct sunlight.

Hundreds of HiRise images reveal rock layering in many different settings: craters, canyons, and cliffs dominated by faulting and pitting. Layers with similar thickness suggest to NASA scientists that some of the observed strata is ancient sedimentary rock that was formed in water and then eroded by wind.

It is believed that Mars is covered with a global layer of permafrost because the annual mean temperature of the soil is approximately -50 Celsius. It is far colder in the northern and southern latitudes – so cold that carbon dioxide gas freezes into a solid and blankets the terrain with dry ice. Therefore, say planetary scientists, any water “must be” bound up with thick icy soils or locked in frigid underground vaults, because the atmosphere is thin enough for water-ice to sublime directly into vapor and vanish. Since ice rather than liquid water is thought to predominate, it “must be” Martian glaciers rather than Martian floods that excavated some of the anomalous terrain.

According to a recent publication, a “large subsurface ice deposit — estimated at the combined size of California and Texas and about 130 feet thick” exists in the high northern latitudes, near Arcadia Planitia. “The fact that the ice is so thick and widespread leads us to think it came into place during one of Mars’ past climates when it snowed a bunch, ice accumulated, was buried, and then preserved,” said Shane Byrne, one of the authors of the study.

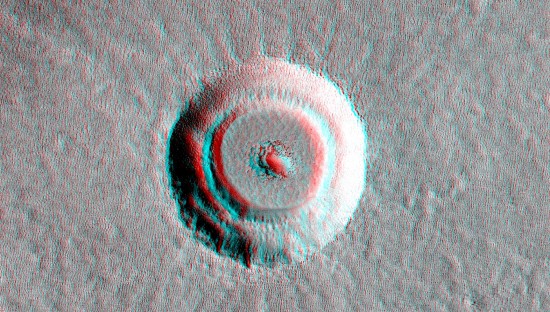

The ice is not directly observed by the research team. Rather, it is the shape of the topography and the terracing in various craters that led them to conclude that massive amounts of water-ice can be found on Mars. Since the craters are terraced and uneven, rather than the bowl-shape expected from “impact events”, Byrne’s team thinks that the anomalous formations are due to subsurface glaciers. Conventional thinking concludes that meteors create a certain kind of crater in the Martian landscape, so when craters exhibit unusual characteristics, it is the substrate that is the cause.

In the 3D anaglyph image at the top of the page, bizarre polygonal structures, thousands of parallel “cracks”, and multiple terraces are clearly visible. The blackened areas in the center of the crater, as well as the hexagons and pentagons with deep channels etched between them, are not the signs of ice and water, they are the signs of electric arcs.

Previous Pictures of the Day about Mars describe the signature of powerful electric arcs that once impacted the planet’s surface. The energy released by plasma discharges took the form of sinuous rilles, flat-floored craters, “railroad track” patterns in canyons and craters, intersecting gullies with no debris inside them, giant mesas with Lichtenberg “whiskers” and steep-sided ravines wending through landscapes dotted with circular uplifts.

If Mars was the scene of planetary lightning bolts and not ice or water moving across the surface, should similar observations on Earth be reconsidered?

Stephen Smith