Aug 17, 2015

Plasma: The New Kid on the Block

Institutional astronomy’s blind spot in intellectual vision is in the beginning. Although astronomers acknowledge that everything they see is plasma, they fail (or refuse) to see the empirically discovered electromagnetic properties of plasma. Habits of thought brand plasma as a fourth state of matter; heedless familiarity imagines it to be an ionized gas; the inertia of prior belief derives its properties from the laws of gas dynamics with a pinch of magnetism stirred in. It becomes “state 3a,” and then just another name for gas. Thought relaxes into its accustomed ways. What’s lost is the insight that the electromagnetic properties of plasma could explain the surprise as each new observation veers away from the expected. Astronomers approach the new observations expecting to see what they believe. They look at a universe that’s 96 percent plasma and see a universe that’s 96 percent unexplainable with traditional theories. So they bridge the chasm with tinkerings.

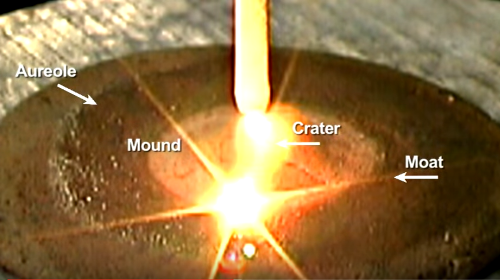

A century of experiments with plasma indicates that it’s not just another state of matter. It’s a pattern of behaviors—electromagnetic activity—that can appear in any state. It’s described by Maxwell’s laws, not by Newton’s or Einstein’s. Maxwell’s laws provide accounts of the new observations that are more coherent, parsimonious, and empirical than Newton’s or Einstein’s: no tinkerings are required.1

Thinking that plasma is an ionized gas shunts subsequent thinking into a visional tunnel of gas dynamics, thermodynamics, and gravitational dynamics. Electrodynamics is overlooked. The importance of moving charged particles in space is dismissed with simplistic electrostatic models that disregard the particles’ movements and conclude that they “don’t do anything” electrically. The fact that moving charged particles constitute an electric current and imply the presence of an electrical circuit goes unnoticed. The moving charges are called “winds” and “rains,” and the meteorological names eclipse the electrical effects. The Bennett-pinch forces in plasma organize matter into filaments; astronomers are surprised to see filaments but dismiss their surprise by calling them “shock fronts” and “gravitational collapse.” Electrons in the field-aligned (Birkeland) currents in plasma emit synchrotron radiation, but the radiation from space is translated into a gas temperature that is surprisingly high or multi-valued. Double layers contain strong electric fields that can accelerate ions to cosmic-ray energies, and the double layers can explode with energies drawn from the entire circuit, with more energy than what is locally available. Being unaware of the laboratory-demonstrated properties of plasma, conventional theorists devise an untestable mechanism for stars to collapse, rebound, generate a supernatural burst of energy, and “fling” charged particles to cosmic-ray energies.

Habit, familiarity, inertia—if you think the same old thoughts, you’ll see the same old neighborhood. Astronomers would never use a telescope without first understanding how it worked and calibrating it. Yet they seldom pay attention to the workings of their primary instrument: their sensory and cognitive apparatus.

Over a century ago, doctors invented a procedure to remove cataracts from people’s eyes. Among their first patients were people who had been blind from birth. The surgery enabled them to see for the first time as though they were newborn. But unlike newborns, they had acquired language and so were able to tell the doctors what they were experiencing.2

They didn’t see “things” that were “out there”; they saw meaningless moving patches of color. The patches were not just confusing in themselves; they caused confusion with other senses as well. The newly sighted persons’ understandings of the world were disrupted. They had to make sense of it all over again. The patients had to learn how to interpret those color patches in ways that were compatible with their other sensations.

This required them to conceive new ideas of “things.” Now a thing is not just a given. It’s a group of sensations that our minds combine into a concept of a unity. We’ve become so accustomed to the process that we take it for granted. But a thing is a cognitive construction from sensory and conceptual bits and pieces. The newly sighted people were awash in these bits and pieces of sensation and had no conceptual structure to make sense of them. They had to develop a concept of “space” in which the things could interrelate.

For the most part, they had no concept of space. “Things” situated in “space” was a totally new way of understanding for them. But before they could learn it, they had to “unlearn” many ways of understanding things and relationships that they had developed without visual sensations. The old ideas couldn’t accommodate the new visual sensations.

The task was difficult. Some patients gave up, closed their eyes, and returned to their old life in the home for the blind. The doctors were surprised to discover that seeing—the understanding of visual sensations as “things” in “space”—was something that had to be learned. By the time most of us can talk about it, we’ve taken it for granted. We take the metaphor literally: seeing is understanding, no interpretation or theory seems to be needed.

The new instruments of the space age have removed the “cataracts” of our familiar biological sensory limitations, and we perceive for the first time patches of new “colors.” We’ve never before seen x-ray or radio “light.” We’ve never before looked at the universe from off Earth’s surface. We’ve never before picked up a handful of Martian dirt. We’ve never before taken a shower in a spray of water from Enceladus. We’ve never before stuck our finger in the high-voltage socket of the Sun.

We must learn again how to see new things in a new space. Not surprisingly, the experts in the old way of seeing are having a hard time learning, and many are taking refuge in the home of blind astronomy. What astronomers think they see is mostly “think” and only a little “see.” The same old thoughts inspired by the trickle of photons from the twinkling stars continue to filter the now swollen stream of photons into the same old colors of theories. Interposing the computer between the telescope and the eye has enhanced the seeing but has turned the thinking into video games. To see plasma in its new, empirical light, we must first unthink the old thoughts.

Mel Acheson

1 See Boris V. Somov, Fundamentals of Cosmic Electrodynamics, Springer, 1994 or Anthony L. Peratt, Physics of the Plasma Universe, Springer, 1992

2 Marius von Senden, Space and Sight: The Perception of Space and Shape in the Congenitally Blind Before and After Operation, Methuen and Co. Ltd., 1960.