Apr 21, 2015

Nebulae exhibit electrical characteristics.

Previous Picture of the Day articles contend for an electrical interpretation of astrophysical observations. Every science journal describes nebulae like IC 1805 in terms of gases and “blowing” dust, along with “winds” created by “shock waves” from exploding stars. In many cases a nebula is described as “star forming,” because intense points of X-ray radiation, or extreme ultraviolet, indicate to astronomers that new thermonuclear fusion reactions have begun within the cloud.

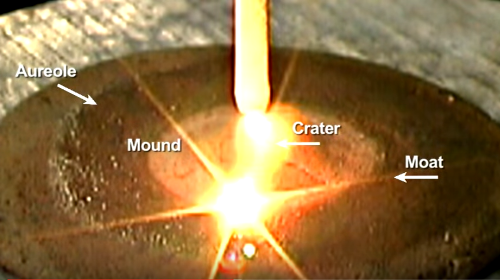

Planetary nebulae are threaded through with strings and webs. Glowing, braided filaments are sometimes visible in “jets” that blast out from stars and some galaxies. The filaments are called “Birkeland currents”, and they are the visible portion of enormous electric circuits that form that large-scale structure of the Universe. The circuits generate magnetic fields that can be mapped, so their helical shape can be seen. Plasma’s behavior is driven by conditions in those circuits. Fluctuations in current flow form double layers with enormous voltages between them. This means that electric forces in double layers can be several orders of magnitude stronger than gravity. Double layers separate plasma into cells and filaments that can have different temperatures or densities.

When electrical stress is low and the plasma contains a small concentration of dust, only the stars in a nebula “light up” in arc-mode discharge. Where electrical stress is greater, as in IC 1805, curling filaments, jets, and any surrounding “gas” clouds can also light up. Of course, dust clouds can reflect the light from nearby stars, but IC 1805 illustrates the characteristic filaments and cell-like behavior seen in plasma laboratory experiments.

The light in the nebula is produced by electrical discharge, so ultraviolet and X-rays can be generated by the intensity of its stellar arcs. Any nebula could be thought of as a laboratory “gas-discharge tube,” similar to a neon light, which emits light because the gas is electrically excited.

When plasma moves through a dust or gas, the cloud becomes ionized and electric currents flow. Charged particles that compose the currents spiral along the magnetic fields, appearing as electrical vortices. The forces between these spinning Birkeland currents pull them close together and wind them around each other into “plasma ropes.” Invisible electric sheaths can get “pumped” with energy from galactic Birkeland currents in which they are immersed. Excess input power might also push them into “glow mode.” Nebulae are ignited with electric triggers.

Stephen Smith