August 30, 2012

A new mission to map the gravity field of the Moon.

On September 10, 2011 NASA launched the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) satellites on a mission to the Moon. GRAIL-A and GRAIL-B are nearly identical spacecraft, except that B is designed to follow A around the Moon in the same orbit. The Lunar Gravity Ranging System will measure the distance between the two spacecraft, watching for minute deflections caused by anomalous mass concentrations or mass deficits beneath the Moon’s surface.

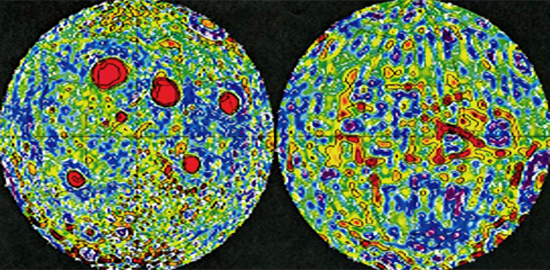

In the image at the top of the page, anomalous areas of increased and decreased expectations were mapped by the Lunar Prospector in 1998-1999. Anything in yellow indicates what computer models of the Moon predicted. Red and purple mean that there is a higher gravity field than expected, while blue and green indicate a lower field. On the left, red concentrations that do not correspond to simulations do correspond to the great maria, or “seas” on the Moon. The five largest are Mare Imbrium, Mare Serenitatus, Mare Crisium, Mare Humorum and Mare Nectaris. On the right, or the farside of the Moon, circular areas of lower gravity can be seen.

There is a major elevation difference between the two hemispheres, as well. The nearside of the Moon is flat, with vast maria, whereas the farside is dominated by mountains and is heavily cratered. This considerable dichotomy is reminiscent of the planet Mars.

In previous Picture of the Day articles, the north and south poles of Mars were contrasted. The south pole on Mars is covered with dust and debris greater in area than the State of Texas, about 430,000 square kilometers. There are thousands of craters at every scale: from the largest crater in the Solar System, Hellas Basin, to those too small to see with the highest resolution cameras.

The north pole of Mars might be considered a crater in itself, since, as terrain mapping instruments in orbit reveal, the northern latitudes are six kilometers below the mean elevation of the planet. Perhaps the central plateau at the pole is the “central peak” of a vast circular formation?

This correspondence to similar features on the Moon is striking. It could be that both Mars and the Moon experienced the same kind of forces at some period. Were those forces the result of impacts by rocky bodies, vulcanism, or flowing water emptying from now long-extinct oceans? Could they actually have come from a source that is rarely considered by planetary scientists: electricity?

Electric Universe theorists presuppose that planets and moons exist within a Solar System that could have been more electrically energetic in the past. Each celestial object is insulated within an individual charge sheath. However, if those sheaths touch, electric charge can be exchanged. Those electromagnetic exchanges are what might have created what we see today.

Magnetic anomalies on the Moon exhibit high albedo material also associated with areas of crustal magnetism imprinted on the lunar surface. It is probable that the magnetic and mass anomalies are related.

When electric arcs pass around a body like the Moon, as it oscillates up and down in an electromagnetic field, they erode material from it. At some time in the recent past, a flow of electric charge appears to have impinged upon the Moon, removing material from one hemisphere (nearside) and depositing it on the other (farside).

Plasma discharges that linger before jumping to another location will excavate a crater while melting the surrounding material. Electrons are yanked toward the center of the discharge channel, ripping apart the rocks and dragging the neutral material along with them. Finely divided dust is then sucked up into the vortex channel and ejected into space. This explains why the bottoms of the lunar maria are smooth and flat, with little or no blast debris. Subsurface electric currents tend to melt and concentrate matter, which may also explain why there are mass anomalies associated with the maria.

Since the hemispheres and not the poles of the Moon are where the most intense activity seems to have occurred, it is not beyond consideration that the Moon is no longer in its original orientation with respect to Earth. What we call the near and far sides of the Moon might once have been the two polar regions.

Stephen Smith