(Left): The Classic image of the winged thunderbolt as shown on the reverse of an 8-litra coin from Syracuse, Sicily, Italy (214-212 BCE). (Right): Sprites over thunderstorms in Kansas, August 10, 2000, observed in the mesosphere, approximately 50 to 90 kilometers above the surface. Their true colour is pink-red. © Walter Lyons, FMA Research, Fort Collins, Colorado, United States of America/NASA

Oct 31, 2013

The discovery of ‘mega-lightning’, upper-atmospheric lightning or transient luminous events (TLEs) is relatively recent, due to the fleeting nature of these phenomena: most last no longer than a few milliseconds.

A menagerie of types – such as the playfully labelled ‘sprites’ and ‘ELVES’ – discharge energetically between the ionosphere and cloud cover, thus completing electrical circuits between the ionosphere and the earth’s surface via ordinary lightning.

It is now recognised that most sprites fall into one of two categories: columniform or C-sprites and carrot sprites, perhaps with jellyfish sprites as a third alternative. The so-called ‘carrot sprites’ are the most commonly reported brand. They are characterised by ‘strong luminous center regions, tapering towards lower altitudes while showing a diffuse ‘hair’ region above the body’: ‘Near the bottom, the carrots are often accompanied by thin hairline discharges or tendrils.’

A remarkable visual similarity joins sprites of all stripes, but especially the carrot, to the classic bilobate representation of the sacred ‘thunderbolt’ in ancient Mesopotamian and Neo-Hittite art, the Graeco-Roman world and India. In these cultures, the iconic symbol of the ‘thunderbolt’ is quite at odds with the familiar appearance of terrestrial lightning.

Carrot sprites have been described as ‘bundles of luminous tendrils that spread outward above and below a central bright ball’: ‘… the branches appear to start from small, localized ball-like features at or near the surface of the volume occupied by the sprite.’ This morphology is also characteristic of the mythical thunderbolt. So the vájra of Vedic tradition, which was carried over into Buddhist mysticism:

‘Its centre is a sphere which represents the seed or germ of the universe in its undifferentiated form as ‘bindu’ (dot, zero, drop, smallest unit). … From the undifferentiated unity of the centre grow the two opposite poles of unfoldment in form of lotus-blossoms …’

In mythology, this curious object is typically placed in the hands of a ‘sky god’ or ‘storm god’ as a weapon against cosmic enemies. For example, Greek mythographers related Zeus’ deployment of such lightning against the Titans during his battle for cosmic supremacy, towards the end of the sequence of ‘creation myths’:

‘From Heaven and from Olympus he came forthwith, hurling his lightning: the bolts flew thick and fast from his strong hand together with thunder and lightning, whirling an awesome flame. … flame unspeakable rose to the bright upper air: the flashing glare of the thunder shone …’

If Mount Olympus, the seat of the wrathful god, is correctly interpreted as a form of the axis mundi and the latter was actually a z-pinch plasma discharge joining the ionosphere to the earth, perhaps the ‘thunderbolts’ emanating from this abode were actually sprites.

Could upper-atmospheric lightning have been more intense and longer-lasting under unstable geomagnetic conditions? The possibility seems genuine, considering that – even under today’s tranquil conditions – ‘Sprites can last longer (tens to hundreds of milliseconds), but at greatly reduced brightness.’ Even at the present time, eagle-eyed people viewing thunderstorms low above the horizon from a considerable distance on an otherwise dark and clear night are occasionally able to make out sprites above the cloud tops. Perhaps incidental observations of sprites in the Mediterranean region of the first millennium BCE kept alive earlier memories of the divine lightning wielded by the gods during the great cosmic wars in illo tempore – a brighter, somewhat less ephemeral prodigy sustained by an electrically more active atmosphere. The same could be true for aspects of the ‘lightning lore’ of unrelated cultures elsewhere.

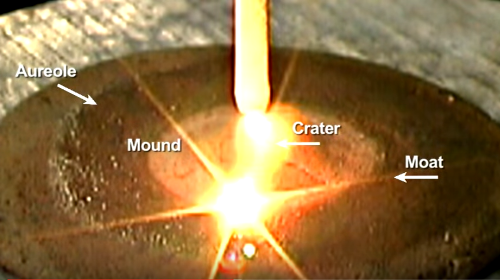

The nuts and bolts of how mega-lightning works physically remain far from understood. The closest experimental match to the complicated discrete structure of sprites – so far overlooked by experts – appears to be Anthony Peratt’s simulation of the evolution of a high-energy-density plasma z-pinch. At a late stage in the sequence, Peratt’s instability column is reduced to a central ‘oblate shape’ with top and bottom electrodes shaped like folded ‘cups’ or ‘arms’ surrounding a central feature:

‘The patterns can be lightning-like, ellipsoidal, triangular …, a lightning bolt or multiple filament current terminations.’

As sprites and Peratt’s Column are both plasma phenomena, but on different scales, it is not inconceivable that sprites are physically equivalent formations to Peratt’s Column, which may have accompanied the appearance of the much larger and more enduring axis mundi itself – fractal-wise. The variant with multiple filaments at the extremities compares to the classical stylisation of the thunderbolt as a flower or a bunch of ‘lightning rods’, whereas the one with cups or toroids corresponds quite naturally to the vájra.

Encouragingly, as the research on upper-atmospheric lightning progresses, an increasing number of properties is observed which match aspects of Peratt’s Column. These include the ‘nearly vertically aligned columns of intense pinpoint like beads’ which constitute ‘the lower altitude luminous filamentary structures of columniform sprites (C sprites)’. This feature reminds of variations on the Graeco-Roman thunderbolt, such as the one with two pinecone-shaped vortices extending in symmetrically opposed directions.

Even the sprightliest of scholars are often loathe to explain enigmatic themes in ancient myth and symbolism in terms of rare, striking streaks of nature. So which will be of most advantage to the thunderous appeal of the sprite hypothesis – the carrot or the stick?

Rens Van Der Sluijs

Click here for a Spanish translation