LOSING CONTEXT

The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

by David Drew

Do you ever think about how you think? Someone once told me I think too much, but I don’t think so.

“When you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.”

Max Planck

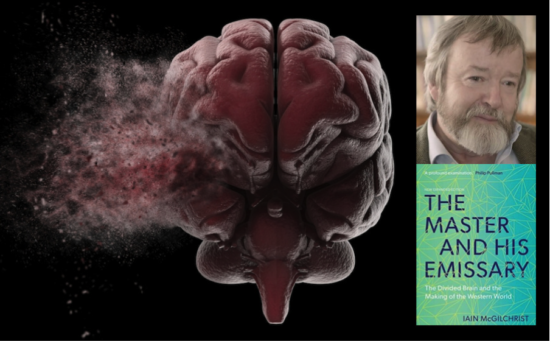

In his 2009 book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, psychiatrist Dr Iain McGilchrist explores the differences between the right and left hemispheres of the brain. The ‘Master’ and ‘Emissary’, respectively. He argues that their differing world views have shaped Western culture since the time of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato, and that a growing conflict between these views has ramifications for the way the world is changing.

Critics, for the most part, praised it as a landmark publication, with plaudits like compelling and profoundly consequential not unusual. For an academic tome, it has achieved remarkable sales.

Spoiler alert! In a book that is as much philosophical as psychological, McGilchrist argues that our increasingly left-brained take on life, the universe, and everything, is not a good thing, for reasons that will become clear. He has spoken on a wide range of issues. His work being especially relevant to cosmology given the paradigm shift already well under way and the inability or refusal of many to recognize as much. Cosmology is known as the queen of the sciences because it provides the building blocks for most other sciences. This only adds to the inertia against change.

To my thinking, McGilchrist’s work represents a breakthrough on a number of levels. For the sake of simplicity, I have split my take on his complex masterpiece into a number of short subtitled sections.

Why is the brain divided?

Philosophically, McGilchrist had long puzzled about the two hemispheres. By the 1980s, however, it was considered pop psychology and he was discouraged from going down this road. Around the same time, the first split brain operations were being performed in cases of bad epilepsy. Together with some earlier work on brain damaged people, it enabled the study of the hemispheres separately, and it was determined there are differences. Big differences. (They are asymmetrical in both form and function.) His curiosity had been vindicated. Furthermore, the hemispheric differences typically promulgated in popular culture are at best misleading. To this day, the left brain is often described as rational and linguistic in nature, and the right as emotional and creative.

Forget everything you thought you knew!

McGilchrist emphasizes that both sides of the brain are engaged in most activities, albeit with different approaches, or “reliably different takes on the world”. It is better to see the two hemispheres as “paying attention in different ways” as he puts it. “It’s not that they do different things, but that they do things differently”.

Significantly, the notion that the left hemisphere is boring but reliable, a bit like an old accountant friend, is untrue. It turns out the right hemisphere is less likely to jump to conclusions. It can see both sides of a question. Distinguished neuroscientist professor VS Ramachandran describes the right brain as an effective devil’s advocate in this respect.

Also, the left brain, contrary to popular opinion, has emotions, and in particular those relating to anger, intolerance, and disgust. In fact, anger tends to lateralize to the left. More on this later.

The everyday brain

When we are learning a new skill, the right brain will be more involved to begin with, but when the task becomes routine the left brain will take over for the most part. While the left hemisphere is good at routine, the right hemisphere is more about the big picture. It recognizes patterns and connections, and therefore provides context. The left sees a fragmented world, and the right puts the pieces together. A more powerful differentiation relates to the whole-oriented nature of the right brain. It is the right hemisphere that will grasp the moral of a story or get the point of a joke.

McGilchrist also describes the right hemisphere as an effective bullshit detector. The left is prone to pathological optimism, and quite capable of living in denial. This relates to the fact that the left hemisphere tends to have a high opinion of itself, and the right hemisphere — sometimes described as the quiet side — a more modest opinion of itself. We are talking hubris vis-à-vis humility. The oft-cited Dunning-Kruger effect springs to mind. “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent full of doubt.”

While both sides of the brain can support consciousness, the point is that they need to co-operate and work together, or as McGilchrist puts it. “The two hemispheres need to inhibit one another and inform one another. They need to stand back and away from one another, and at times to work in unison. They have an interesting relationship which is oppositional but by no means contradictory … the left should always be in service to the right. It makes a very good servant but a very poor master.”

He stresses the hemispheric differences are not about what they do in any machine sense, but about how they do it in a human sense. The right brain is more interested in people, and the left in things.

Brain damage

Given both sides of the brain are involved in most activities, this has led some to believe there is little difference between them. To support this view, it is sometimes claimed those with damage to one hemisphere can recover to lead normal lives with the other hemisphere taking over. Again, this is over generalized. As McGilchrist has demonstrated, there are fundamental differences in the way the left and right brain attend to the world.

Moreover, research indicates the right brain is better able to take over after trauma. Damage to the right brain generally has more serious consequences for the individuals concerned. This might seem surprising given the left brain is more closely associated with the routines of everyday living, but the mass of evidence supports as much.

“The left brain thinks it is always right … I have often dealt with patients with right hemisphere strokes that simply cannot be moved away from a belief that is obviously false.”

Interestingly, there are numerous anecdotes about those becoming more dependent on the right hemisphere being described as more pleasant people by those who know them. Damage to the right hemisphere can result in difficulty recognizing people, even loved ones. Again, this is because the right brain pieces the picture together after the left brain sees the details. After a stroke, right hemisphere damage can also result in a drop in IQ, although this is rarely the case with the left.

Without the right, the world is stripped of value, depth and meaning.

Language and metaphor

Metaphors act like bridges between words and experience or reality. They can be essential for expressing deeper meaning. The right brain is associated with metaphor in line with its aptitude for understanding the bigger picture. Here are just a few metaphors that spring to mind, all of which are more evocative than simple descriptive language. The latter from Thunderbolts.info.

A blanket of snow, eyes like diamonds, life is like a highway, a heart of stone, the heart of a lion.

Dark matter and dark energy are the blank cheques required to postpone the falsification of bankrupt theories!

McGilchrist describes metaphor as a “…crucial aspect of language whereby it retains its connectedness to the world…”

He goes further:

“Language has done its best to obscure its parentage. It has increasingly abstracted itself from its origins in the body of the experiential world … And the understanding of language at its highest level, once the bits have been put together, and making sense of its utterance in its context, taking into account whatever else is going on, including the tone, irony, sense of humour, use of metaphor and so on, belongs again with the right hemisphere.“

Iain McGilchrist The Master and His Emissary. P 125, Language, Truth, and Music.

Lateralization

Laterality refers to the development of specialized functioning in each hemisphere of the brain. One obvious example being handedness, which is the tendency to use one hand or the other to perform various activities.

Notably, there is a trend for gifted creative and athletic people to be left-handed. In other words, the right hemisphere is more dominant in their everyday lives. It is estimated that about 90% of the world population is right-handed (left brain dominant). In biological terms, the right brain is connected to the left side of the body and vice versa, although the situation is more complicated with vision. The left visual fields of both the left and right eye are connected to the right brain.

Handedness aside, and according to McGilchrist, it is becoming apparent that increasingly specialized training in differing disciplines, together with the pressures of modern-day living, have contributed to most people ‘living’ in the left hemisphere of their brain.

The left hemisphere is designed to help us ap-prehend the world – and thus manipulate it, and the right hemisphere to com-prehend it – to see it all for what it is. The problem is, in simplifying and subjecting the world to our control, do we lose a true understanding of it? Compounding the problem, do we take the success we have in manipulating it as proof that we understand it? By way of a simple everyday example, we don’t need to understand the mechanics of a motor vehicle in order to drive it, and it is all too easy to overlook the potential dangers of controlling a ton of glass and metal when we get behind the wheel.

“The left-hemisphere is the one that seeks power. It manipulates. It enables us to grab and get. (It controls the right hand.) From its point of view, anything that stands in its way is some kind of unwelcome constraint.”

Iain McGilchirst, Rebel Wisdom interview, WE NEED TO ACT, 7:00 mins

McGilchrist describes the left brain’s narrow beam of focus as goal oriented, and adversarial in its general view. A theatrical metaphor seems useful in this respect. The left brain is like a spotlight on a dark stage, with a narrow focus. The right, meanwhile, can understand the broader narrative. Along similar lines, a notable piece from the Thunderbolts Project described the cosmic theatre as having outgrown the Newtonian stage. It is certainly true that, for decades now, consensus science has viewed the universe through the narrow lens of gravity alone.

Specialization

In terms of specialization, I am reminded of a book I read many years ago. Rich in metaphor, Lateral Thinking by Edward de Bono (1933-2021) was published around 1980. De Bono argued that specialists dig their own holes, but at a certain point they are unable to see outside them.

I am reminded of a coarse expression I have occasionally heard in the work place. “Experts get to know more and more about less and less until eventually they know everything about f#! a! [not much].”

McGilchrist argues that blinkered left hemisphere training very often renders students functionally blind to alternative ways of looking at problems. “The left hemisphere simply blocks out everything that doesn’t fit with its take.” Many scientists, with their narrow, specialized training, may not be able to see what to a non-expert is obvious. After digging their own holes – to borrow De Bono’s metaphor – they will probably be the last to see a paradigm shift in the making.

An interdisciplinary approach, by contrast, recognizes the importance of communication between different disciplines, not least because so many scientific breakthroughs have come from unexpected sources outside their own field. The right brain being better equipped for this broader view. After all, what are scientific disciplines if not different pieces of the same jigsaw puzzle?

“There are none so blind as those who have learned not to see.” —Michael Armstrong, Natural Philosopher

The specialization problem puts me in mind of another common expression: Seeing is believing. But is it true? Do we believe what we see, or do we tend to see what we believe? In other words, are we are prone to interpret what we see according to our preconceived notions?

“Most of the great discoveries in science were made intuitively through pattern recognition — through seeing Gestalt. They weren’t necessarily made by following a linear sequence. The right brain sees no conflict between science, intuition, imagination, and reason. In good science they all work together. In other words, there is no reason for these things to be set-up or talked about as if they are somehow in conflict with one another.”

McGilchrist in discussion with Jordan Peterson, The Matter with things v

The chaos of bits

McGilchrist refers to the left brain’s tendency to see the world as black and white, and its habit to categorize, as the chaos of bits. Here we can see an obvious corollary with cosmology. The Big Bang and Gravity Only Cosmology see the universe as mechanical and disconnected after the initial explosion or expansion. In this world view, effectively nothing has meaning. It’s no more than the randomn collision of elements of matter, made up of isolated and decontextualized fragments, where life is essentially purposeless.

The plasma view, meanwhile, promotes a connected (you might say holistic) view of the universe.

“From the smallest particle to the largest galactic formation, a web of electrical circuitry connects and unifies all of nature… There are no isolated islands in an Electric Universe.” —David Talbott and Wallace Thornhill, Thunderbolts of The Gods

There is more going on that the haphazard collision of matter. A picture can say a thousand words:

The Milky Way galaxy pictured through a standard telescope, left, and an electron telescope, right, revealing its filamentary structure — the threads of plasma which connect stars and galaxies. Were Sherlock Holmes a Cosmologist, he might have said: “It’s Filamentary my Dear Watson.”

As a matter of fact, Irving Langmuir (1881-1957) coined the term ‘Plasma’ in 1927 — borrowing it from Blood Plasma — to describe the life-like and self-organizing behaviours of plasmas in the presence of electrical currents and magnetic fields. Too many remain ob-li-vious to the obvious. The li is that the universe is dominated by gravity alone.

In a metaphysical sense, McGilchrist describes “consciousness as the stuff of the cosmos”.

“Our talent for division, for seeing the parts, is of staggering importance – second only to our capacity to transcend it, in order to see the whole.”

Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary

Left versus right

Could it be that the left and right hemispheres of the brain have somehow come into conflict?

“The sheer vehemence with which the right hemisphere has been dismissed by the representatives of the articulate left hemisphere, despite its overwhelming significance, suggests a possible rivalry. I believe there has been until very recently a blindness among neuroscientists to the contributions made by the right hemisphere.”

Iain McGilchrist, P 129, Language, Truth, and Music. The Master and His Emissary

Pejorative terms for the right brain are not uncommon in the neuroscientific literature of the last 100 years. In addition to “inferior” and “silent”, which were commonplace, Salomon Henscher had this to say in an influential paper contributed to Brain in 1926:

“In every case the right hemisphere shows a manifest inferiority when compared with the left, and plays an automatic role only … the question therefore arises if the right hemisphere is a regressing organ … it is possible that the right hemisphere is a reserve organ.”

While it might be amusing to reflect on the mistakes of the past, the trouble is that such misconceptions can enjoy a long shelf life. It seems it wasn’t just pop psychology that got a lot wrong.

“My thesis is that for us as human beings there are two fundamentally opposed realities, two different modes of experience; that each is of ultimate importance in bringing about the recognisably human world; and that their difference is rooted in the bihemispheric structure of the brain. It follows that the hemispheres need to co-operate, but I believe they are in fact involved in a sort of power struggle, and that this explains many aspects of contemporary Western culture.”

Iain McGilchrist 2009, Language, Truth, and Music. The Master and His Emissary

McGilchrist explains that this “power struggle” is only a conflict from the left hemisphere’s point of view. After all, the right hemisphere knows it needs the left (the administrator or emissary, which it appointed), but the left doesn’t know it needs the right. The left is a bit like an adolescent child in this respect, perhaps. It thinks it can do just fine on its own, although in truth it needs the right in order to see Gestalt — to see the whole.

Reason and Rationality

The words reasonable and rational are often used as synonyms, although they are not. In chapter 30, McGilchrist discusses these terms in the context of the Enlightenment, sometimes referred to as the Age of Reason.

“Rational and rationality, reason and Reason, remain hotly contested notions, whose users disagree even about the nature of their disagreement.” —Max Black, philosopher

Reason, in English, conveys the same meaning as Intellectus in Latin, and is allied to common sense, which is more intuitive in nature, whereas rationality, from the Latin ratio, is about consistency, or the internal coherence of any system. Reason is about lived experience and tends to resist formulation. It’s about the big picture. Rationality is more rigid, and governed by explicit laws. There is an obvious problem with the latter. Opposites, as we know, can be true. There are many paradoxes. Change is a constant, for example. Rationality, therefore, fails by its own definition. It contravenes the consistency principle. It falls on its own sword.

In other words, reason (relating to the right brain and the big picture), always trumps the limitations of rationality (the left hemisphere’s desire for consistency or internal coherence). Sometimes we just know something to be right or wrong, and this knowing can never ultimately be formularized. Common Sense, to a large degree, is always intuitive in nature. Reason encompasses rationality, but rationality doesn’t encompass reason.

“The rational mind is a faithful servant, and the intuitive mind a precious gift. We live in a world that honours the servant, but has forgotten the gift.” —Albert Einstein

Today we see systems in place across most disciplines, and we are generally rewarded for cohering with these systems rather than daring to challenge them. Progress is easily stifled in this way.

“The left hemisphere sees truth as internal coherence of the system, not correspondence with the reality we experience.”

Iain McGilchrist, The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning, YouTube (ii)

Myth and Legend

I have lost count of how many times I have heard all myth (https://plasmacosmology.net/myth.html) and legend dismissed as the result of ignorance and superstition, long left behind in our rational age. Contrariwise, when we focus on the key points of agreement, perhaps the ancients have something far more interesting to say, and certainly less deserving of contempt and superior cynicism.

To take just one example, Thunderbolt imagery is widespread the world over, but few scholars and scientists ever pause to wonder about this ancient fascination. After all, most researchers routinely assume the old sky was essentially identical to what we see now. As today so before, is their default.

But, if the skies were more electrically active in the past, might this account for the enigma? Unsurprisingly, such a notion is anathema to the gradualist paradigm.

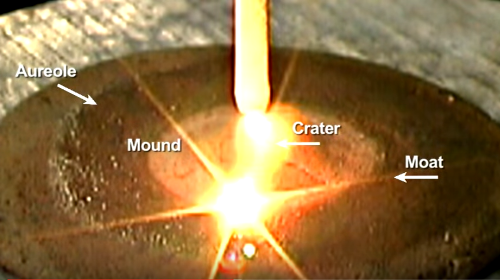

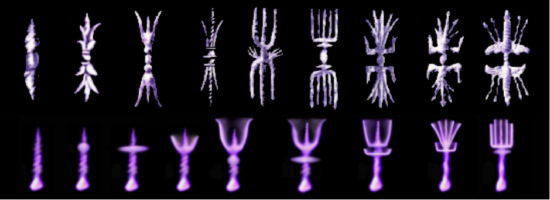

The visual similarities between Greek representations of the classical Thunderbolt, above, and laboratory discharges, below, are noteworthy. More than just a coincidence?

“Myth in the modern mind is almost synonymous with falsehood. In ancient Greece, mythos was thought to be a greater truth than logos.” —Iain McGilchrist

In another example, the idea that rocks (meteors) could fall from the sky was denied by several of the best minds of the 18th and 19th centuries. It was dismissed as too ridiculous to merit serious discussion, although the fact was well known to the ancient Sumerians and others. All but lost for several millennia, such knowledge is once again commonplace among schoolboys the world over.

The origins of consciousness

My interest in the differing hemispheres of the brain was piqued some years back by Julian Jaynes eccentric book, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, published 1976, partly because there is some overlap with catastrophism related thought, but that’s another story. Jaynes was not a catastrophist in any conventional sense.

Jaynes posited that consciousness (in terms of introspective self-awareness) emerged around the second millennium BCE when the bicameral mind (separation of hemispheres) broke down, leading to the left hemisphere suddenly having access to the right, and mistaking its own intuitive thoughts (inner voice) for the voices of the gods (or God). Strange as this may sound, Jaynes provided some compelling arguments to support his case.

He argued that when the heroes of the Iliad and the Old Testament heard voices giving them commands or advice, they literally heard voices. The voices were their own intuitive thoughts arising from their own minds, but were perceived as external because at the time man was only just becoming aware of his own (hitherto unconscious) intuitive thought processes. Also, when Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors landed in South America, they were surprised to discover that many of the natives saw and heard their statues talking to them … again, in a literal sense. The statues very often formed a focal point for their community. Jaynes believed this provided some insights into disorders like schizophrenia, given that schizophrenics hear voices, ergo, the disorder relates to a regression to an earlier state of mind. This hypothesis seems reasonable on the face of it, but McGilchrist has a different take.

“Putting it at its simplest, where Jaynes interprets the voices of the gods a being due to the disconcerting effects of the opening of a door between the hemispheres so that the voices could for the first time be heard, I see them as being due to the closing of the door, so that the voices of intuition now appear distant, ‘other’, familiar but alien, wise but uncanny – in a word, divine.”

Iain McGilchrist, P 262, The Ancient World. The Master and His Emissary

Moreover, McGilchrist points out that there is little if any evidence for the existence of schizophrenia before the 18th century. He goes on to explain that — contrary to some popular opinion — the left brain is dominant when a subject is under hypnosis, or during a schizophrenic episode. In fact, he sees hyper-rationality as a defining quality of modernity: “Both schizophrenia and the modern condition,” he notes, “deal with the same problem: a free-wheeling left hemisphere.”

“Our culture is becoming more autistic.” —Iain McGilchrist

McGilchrist’s work benefits from decades of further research, of course. He recognizes that Jaynes was close to making an important breakthrough, and indeed did so in some respects.

Prior to the breakdown of the bicameral mind, Jaynes proposed that mankind lacked the same degree of self-awareness we enjoy today, acting much like an automaton as if under the influence of some form of collective consciousness. That’s a different rabbit hole, though, and not strictly relevant for now. Suffice to say that we are more self-ish today, literally and metaphorically.

Revolutions in thinking

Karl Popper is one of the most influential philosophers of science. His methodology Falsificationism proposed the idea that science progresses gradually, step by step, towards truth. Contrarily, Thomas Kuhn argued — successfully in my view — that science undergoes periodic upheavals. Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, was influential in both academic and popular circles. Again, I see some overlap with McGilchrist’s work. In reality, I believe the specialist left-brain is frequently either unwilling or unable to recognize significant developments outside its own field, either hindering or remaining blissfully unaware of them and their implications.

Kuhn’s work puts me in mind of Max Planck’s famous quote.

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” —Max Planck

Science that has become dogmatic and ideological is sometime referred to as scientism. Such dogmas can take time to overcome, as Kuhn documented in his groundbreaking work.

Philosophy and skepticism

The philosophical derivation of the term skepticism means to deny certainty. It is at the heart of good science. Unlike faith-based systems, science seeks to continually test and improve itself. At least this is the ideal.

“I would rather have questions that can’t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.” —Richard Feynman

The nature of consciousness and the workings of the brain are inextricably linked with philosophy; the study of knowledge. Given the brain is where mind meets matter and it is the ‘tool’ we use to make sense of the world, it would seem impractical, not to mention nonsensical, to take it out of the equation. McGilchrist points out that the left brain is more likely to arrive at a mechanistic view of the universe given its simplistic and reductive take on things. Problems with a modern-day brand of skepticism, often referred to as one way skepticism or pseudo-skepticism, add weight to this conclusion.

“What men really want is not knowledge but certainty.” —Bertrand Russell

SkepticalaboutSkeptics.org have done some excellent work exposing the questionable motivations of a number of prominent ‘skeptics’ who seem utterly certain of their own world view. The web site is well worth a visit. Ironically, the militant brand of atheism that characterizes a number of these individuals is somewhat akin to a cult like or fundamentalist mentality. Their modus operandi is to lump all alternative and competing theories into the same basket and accuse them of irrationality, while at the same time accepting conventional wisdom less critically. (Conventional wisdom, as I am fond of saying, usually owes at least as much to convention as wisdom.) This is not skepticism in its true philosophical sense.

“I would also like to put in a word for uncertainty. In the field of religion there are dogmatists of no-faith as there are of faith, and both seem to me closer to one another than those who try to keep the door open to the possibility of something beyond the customary ways in which we think, but which we would have to find, painstakingly, for ourselves … Certainty is the greatest of all illusions: whatever kind of fundamentalism it may underwrite, that of religion or science, it is what the ancients meant by hubris. The only certainty, it seems to me, is that those who believe they are certainly right are certainly wrong.”

Iain McGilchrist The Master and His Emissary. P 460, Conclusion, The Master Betrayed.

It is easy to understand the attraction of the mechanistic world view because it is simple to articulate. This primitive ontology has many prominent and noisy advocates who delight in ridiculing different ideas, and they enjoy plenty of traction in mainstream media. Humility isn’t generally their strong point. Again, the Dunning-Kruger effect jumps to mind. The less you know, the more you think you know.

Welcome to the machine

The brain as a machine may have served as a useful metaphor, but the biochemical machinery of the brain is now so deeply embedded in current neuroscientific thinking that many neuroscientists seem to have forgotten that it is a metaphor, and tend to view the brain as a machine rather than a personality. This has given rise to another ugly mechanical metaphor, the human as a lumbering robot or, worse, humans as faulty machines.

In the context of transhumanism, much talked about today, the machine analogy is often invoked. The assumption being that we (faulty machines) might be improved with a bit of tinkering such as the insertion of the odd microchip or two, and/or a little gene therapy. This is a contentious subject matter because many see it as a potentially dangerous path, needless to say.

It seems we have a paradox of sorts. While there appears to be more to the nature of consciousness than mere biochemical machinery, the problem is that the left hemisphere, ipso facto, sees everything as a machine. It has a proclivity for taking things literally. It is the right hemisphere that is required to break out of the loop…but the left will resist.

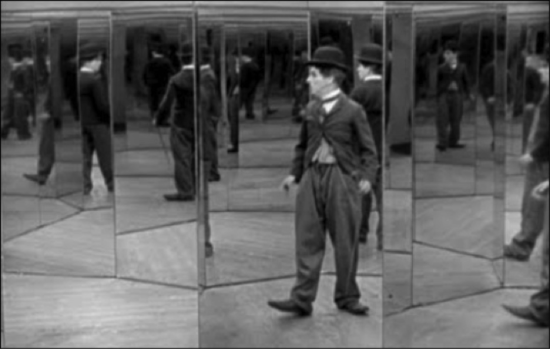

McGilchrist likens the left hemisphere to a hall of mirrors. It can be self-referential. Talking of which, in another interview with the YouTube channel Rebel Wisdom (ii), McGilchrist offers a Sat Nav anecdote. I laughed out loud because I had a similar experience recently. A taxi driver insisted we had arrived at the specified location because his Sat Nav told him so. It wasn’t even close, and the driver had earlier refused my advice based on local knowledge, preferring to listen to the disembodied voice emanating from his device. Similar anecdotes abound about people following their Sat Nav off the end of a pier and so on.

“I often call the left hemispheres generated world a hall of mirrors because it doesn’t see anything outside itself has created. It is this tiny bit of our mental life of which we are now conscious…”

Iain McGilchrist, Rebel Wisdom interview, YouTube (iv)

McGilchrist argues that the West in particular, but also the East, is moving towards a set of values served by the left hemisphere, which is interested primarily in command and control. While there is nothing wrong with bureaucracy in itself, he stresses that it becomes dangerous when it begins to take over our lives. He warns that technology and administration are working together to create a situation from where it may be difficult to extricate ourselves with dignity. “Technology is only as good as the people who are using it, and there is certainly a tendency for the excitement of power to bring out the psychotic and narcissistic in people.”

—CONCLUSION—

The Master Betrayed

The conclusion of McGilchrist’s book is entitled The Master Betrayed. This makes eminent sense.

While the workings of the brain are a big and complex subject matter, as demonstrated by his magisterial tome, it is nonetheless possible to draw some straightforward conclusions based on decades of research. McGilchrist shows that while the left brain might be a wonderful servant, it makes for a very poor master. The right brain is more reliable and insightful. Without it our world is stripped of value, depth, meaning, and a sense of the sacred.

Despite much talked about globalization, in so many respects we seem to be living in an increasingly divisive world. In my opinion, his work provides some big clues as to where we are going wrong. It seems clear to me that a lot of experts have dug their own holes and are happy to lie in them so long as the money pours in. From politics and economics to science and medicine. Have we lost sight of the bigger picture? (It should be noted that the cerebral hemispheres do not map to the left and right in politics. Any form of extremism reflects the left-brain tendency to see the world in black and white.)

From Understanding The Matter with Things Dialogues Episode 9: Chapter 9 Schizophrenia and Autism, YouTube (iii)

“We are headed straight into good old fashioned psychosis. We are completely mad as a civilsation, in my view. This is not because we all have schizophrenia, but because this is precisely the way the left hemisphere thinks when it has complete control, of course … when it has no counter-balancing from the grounding effects of the right hemisphere.”

Questions naturally arise. Is the move to left brain bias inexorable? And How might we restore some balance? I don’t pretend to know the answers, but acknowledging the fact that there are problems with our current take on life, the universe, and everything, seems like a good start. We certainly need to re-envision the world.

Abstraction, by definition, means removal from context, and is therefore very much within the remit of the left brain. Today, so many fields of human endeavour seem to have been removed and deconstructed from reality. McGilchrist talks about ideas about things becoming more important than the thing itself. He refers to this as re-presentation, “when things are replaced by concepts, and concepts become things.”

“Meaning emerges from engagement with the world, not from abstract contemplation of it.”

—Iain McGilchrist, The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning

Later, we’ll take a look at some contemporary controversies which, in my humble opinion, highlight the problematic aspects of left brain-dominance under discussion.

Cosmology and insanity

From an Electric Universe perspective, the inertia of prior belief and vested interests (grants and prestige), are often talked about in terms of having a negative effect on progress. Reification is another problem, which McGilchrist talks about in terms of re-presentation, where speculative ideas are made ‘real’. Cosmology provides a number of classic examples in this respect. According to conventional wisdom, the universe is now made up of approximately 90% dark matter and dark energy, the exotic hypotheticals required to patch standard theory. Without these generous fudge factors gravitational cosmology falls down, and yet they remain elusive beyond wishful thinking.

“It is an embarrassment that the dominant forms of matter in the universe remain hypothetical!” —Jim Peebles, Princeton

How did pop science get there? Do they really think their models can’t be wrong…so the universe must be in the wrong, or hiding something from them?

Mathematical speculation and abstraction, sometimes jokingly referred to as ‘mathmagics’ is a central plank in this mindset. The Black Hole hypothesis, originally a place holder, has become ‘reality’. Despite being based entirely on theoretical assumptions, it has collapsed into certainty. Black Holes now literally suck up tax dollars. Sure, we witness compact energetic activity at the center of galaxies, but can gravitational theory alone account for it? Popular science textbooks typically describe black holes as one of the most successful predictions of general relativity, yet conspicuously neglect to mention the fact that Einstein dismissed the idea. In a 1939 paper in the Annals of Mathematics Einstein concluded that the Black Hole hypothesis was ‘not convincing’ and the phenomena did not exist ‘in the real world’. How often do you hear this from consensus sources? The paper is now hidden behind a paywall, but there is also reference to it at History.com.

With much fanfare, in 2019 it was claimed that a Black hole had been pictured for the first time? There is good reason to doubt this, however. From my website plasmacosmology.net – The hype conflicts with the science.

Then we have the Big Bang theory, perhaps best summed up by Terry Pratchett.

“In the beginning there was nothing, which exploded!” —Terry Pratchett

Is this level of abstraction healthy? So much popular science is built on speculation, ignoring falsifying instances, and selectively interpreting observations to fit rather than following the evidence and leaving the big questions open. Can we really be sure how big or how old the universe is? Halton Arp’s work on Redshift anomalies has certainly thrown the expanding universe hypothesis a curveball.

Again, could this requirement for certainty over genuine skepticism be another symptom of left-brained myopia? To draw another parallel with the left brain, and with particular reference to cosmology, has the role of mathematics become dominant rather than ancillary? In more simple terms, math should be based on science, not science on math. The latter is putting the cart before the horse, not to mention hubristic.

“Physics is to math what sex is to masturbation.” —Richard Feynman

Hannes Alfvén, the father of plasma physics and plasma cosmology, put it less crudely at his Nobel prize acceptance speech. “The underlying assumptions of cosmologists today are developed with the most sophisticated mathematical methods and it is only the plasma itself which does not ‘understand’ how beautiful the theories are and absolutely refuses to obey them.”

All this is not to say that today’s mathemagicians are totally deluded or less then intelligent. Far from it. After all, they’ve effectively invented a perpetual funding machine.

All of the above is perfectly summed up by Wallace Thornhill, the founder of the Electric Universe, who sadly passed over recently. This YouTube video was reposted in tribute to him.

Toxic social media

I am not suggesting all social media is toxic. I too have a soft spot for watching mischievous Panda bears frolicking with Chinese zoo keepers. Fun aside, though, it is no revelation to observe that social media can quickly descend into generalization and ad hominem attacks. The fact that Tweets are restricted to a limited number of characters doesn’t help. Complex issues can easily be oversimplified and, given the virtual anonymity afforded by the internet, just about anyone can call themselves a fact checker in order to denigrate alternative views. People who wouldn’t normally say “boo” to a goose suddenly turn into aggressive keyboard warriors. Furthermore, algorithms that encourage engagement through attention seeking behaviour only serve to increase polarization and animosity. Terms like conspiracy theorist, denier, and even Nazi are thrown about with reckless abandon. The Thunderbolts Project has certainly suffered its fair share of online Trolls over the years.

The black and white tendency of the left brain appears to play its part. Complex issues are all too often reduced to binary choices. Any legitimate concerns about Covid vaccinations, related mandates, and lockdowns, for example, were frequently dismissed as anti-vax conspiracies, much as anyone who dares to question various aspects of the AGW (Anthropogenic Global Warming) narrative is quickly labelled a denier. The list goes on.

“Anger has become almost the most dominant timbre of discourse in social media, and even the public sphere. Anger, intolerance, and a sense of self-righteousness, accompanied by a sense of disgust with anyone who is different.” Rebel Wisdom interview 32:30 mins i

The mainstream media are no better on occasion. A UK Guardian article attacked the recent Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse focusing on the work of Graham Hancock, insinuating links with far-right ideology. An accusation which is ridiculous in any reasonable analysis. I might not agree with Hancock’s conclusions, but he highlights some interesting anomalies which challenge conventional wisdom regarding human history. He deserves to be heard.

From the Guardian article…

“Millions have watched Netflix hit Ancient Apocalypse, which is just the latest interpretation of an enduring tale. But in its appeal to ‘race science’ it’s more than merely controversial.”

I guess they are too late to cancel Hancock’s series given it is already successful in terms of viewing figures, but insinuating racism is a cheap shot. Hancock found this upsetting because he has mixed race children from his marriage to an Asian woman.

The situation reminds me of the Velikovsky Affair in the 50s, when successful attempts were made to sideline him by underhand means. His publishers, Macmillan, intimidated by threats from academics and scientists, transferred his controversial book Worlds in Collision to Doubleday. Prominent people also engineered the dismissal of the veteran senior editor at McMillan — despite his 25 years plus service — for initially accepting its publication. The same scientific establishment lobbied the FCC to fine NBC for airing an alternative view in 1996, when they ran the series Forbidden Archaeology.

Big science acting like big brother obviously isn’t a good thing.

Cancel Culture

The mob mentality which seeks to silence dissenting opinions in popular culture is sometimes referred to as Cancel Culture. As we can see, it has been around for a long time, although it is more pronounced today than ever.

Not wishing to get into the politics of it all, suffice to say their tactics are sometimes effective in closing down opposing views. The British author responsible for the best-selling Harry Potter children’s book series, JK Rowling, was accused of transphobia when she used the term ‘biological women’ in an attempt to differentiate them from transwomen. For this sin, she was disinvited from a much-vaunted Harry Potter reunion party! The very success story she created. She was also removed from the Guardian newspaper’s birthday list.

“The left brain has no sense of nuance, or of there being alternative views. The left brain tries to construct its own reality, and tends to get very angry and self-righteous.”

Iain McGilchrist, Rebel Wisdom interview i

In a YouTube interview with Rebel Wisdom, WE NEED TO ACT (vi), McGilchrist raises concerns about proposed limitations on free speech, which are typically couched under the auspices of restrictions on hate speech. He notes that many who describe themselves as liberal are anything but, and actually illiberal, drawing parallels with the former USSR. Free Speech not Hate Speech is the hollow mantra often shouted by sometimes well-intentioned radicals. The problem being that dissenting opinions are easily labelled as hate speech or similar with no good reason. Witness the scurrilous hit piece on Graham Hancock in the Guardian.

As mentioned earlier, emotions like anger, intolerance, and disgust are known to lateralize to the left hemisphere, resulting from its tendency to see the world in black and white.

“It is only the left brain that thinks there is certainty to be found anywhere.”

Iain McGilchrist The Master and His Emissary. P 171, The Nature of the Two Worlds.

Consider the fate of Liverpool, UK, teenager Chelsea Russell who found herself on the wrong side of the law in 2018. After her friend died in a road accident, she paid tribute to him by posting the lyrics of his favourite rap song, Snap Dogg’s I’m Trippin’, on Facebook. Unfortunately, the lyrics contained some racist language. The N word, to be precise. Many rap songs do, as it goes. Russell was convicted of sending a grossly offensive message by a public communication, fined almost 600 GBP (approx. 800 USD) in total, given an eight-week community order, and placed on an eight-week curfew. Given the clear context of her actions — a tribute to a recently deceased friend — the legal action seems petty and ridiculous in the extreme. (SOURCE: bbc.com)

“Tolerance will reach such a level that intelligent people will be banned from thinking so as not to offend the imbeciles.” —Fyodor Dostoyevsky

What possessed the police and law courts to prosecute for such a trivial transgression? What were they thinking? I could quote similar examples ad nauseam from the UK.

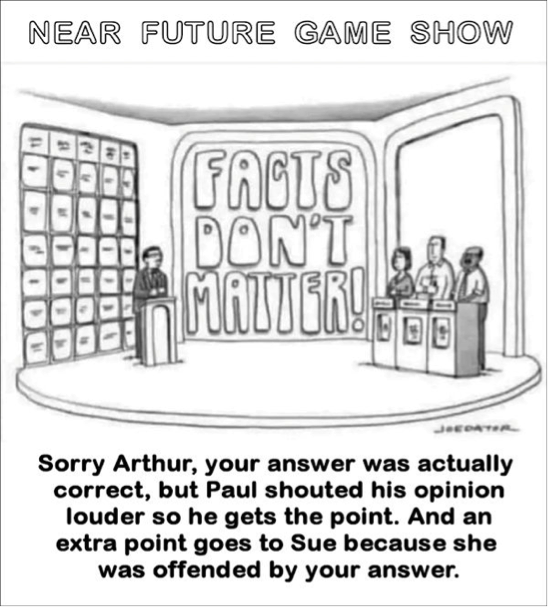

I found the above cartoon amusing in the light of recent trends, but many on social media described it as toxic. Mostly those it was taking aim at, of course — the type who consider comedy hate speech and laughter a gateway drug. Is this another example of a limited left-brained take on the world?

“A sense of humour comes from a sense of proportion, and if you can’t exercise a sense of humour, and if you don’t exercise a sense of humour, then things will become disproportionate.”

Iain McGilchrist i

I wish I could disagree with McGilchrist when he says “we are completely mad as a civilization and heading for a good old-fashioned psychosis.” However, the ideological approach that continues to dominate in so much ‘science’, together with poisonous cancel culture and recent bizarre decisions in ‘law’, appear to add weight to his conclusion.

It’s not funny, but it makes you think.

—Addendum—

Seeking Balance

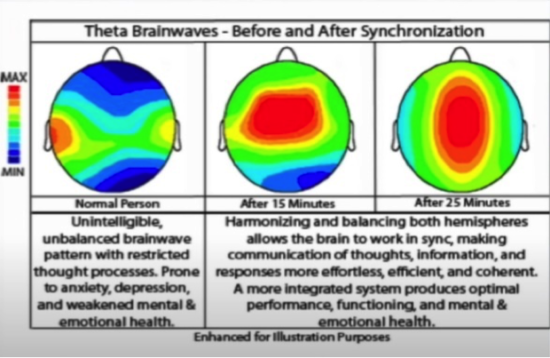

The likes of Yoga, meditation, listening to classical music, and good sleep patterns, are frequently touted as useful tools for balancing the left and right hemispheres of the brain, among others. Another method comes from an unlikely source. I say unlikely as altruism isn’t necessarily the first thing that springs to mind as their raison d’être.

According to the links below, in a declassified CIA document from 1983, a method for synchronizing the hemispheres of the brain using sound, resonance, and electromagnetism is detailed.

CLICK FOR PDF ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF GATEWAY PROCESS

There is an interesting YouTube analysis here:

The Gateway Process: the CIA’s Classified Space & Time Travel System That You Can Learn

David Bohm, a well-known name in plasma circles, is one of many experts cited. Among other things, the document has the following to say:

“… consequently, the Gateway process is designed to rather rapidly induce a state of profound calm within the nervous system and to significantly lower blood pressure … as the body is turned into a coherent oscillator in harmony with the surrounding electrostatic medium … presumably by using energy from the Earth’s field which the body is now entraining because of its ability to resonate with it … and promotes movement of the seat of consciousness into the surrounding environment…”

David Bohm

It even speculates about this state of mind being ideal for telepathic communication. The nomenclature is in itself interesting. In popular culture the term Gateway often means something like an entry point to a different world or dimension. This all sounds a bit hippy-dippy, I know. I just thought I’d put it out there.

Links

i Rebel Wisdom, YouTube, WE NEED TO ACT, 4:00 mins.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=686heq5QFPk

ii Rebel Wisdom, The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning, The Matter with Things

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U99dQrZdVTg

iii Understanding The Matter with Things Dialogues Episode 9: Chapter 9 Schizophrenia and Autism, 46 mins

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAalKyb5Gto

iv Rebel Wisdom interview, We Need to Act, 19:10 mins

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=686heq5QFPk

v McGilchrist in discussion with Jordan Peterson, The Matter with things 44:18

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6Vkhov_qx8

vi Rebel Wisdom interview, WE NEED TO ACT https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=686heq5QFPk&t=741s

vii Iain McGilchrist & Isabela Granic: Intergenerational Wisdom for a World Unravelling

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agPnrBRAldk&t=1962s44:00 at 44:00 mins

David Drew, who hails from the UK, has enjoyed a long interest in science, philosophy, and cosmology. He has been involved with the Electric Universe since around 2004 and published his own website, plasmacosmology.net in 2006. The purpose of his website is to provide an introduction to the emerging Plasma Universe paradigm and to explore some of the many far-reaching implications. David was the first to publish videos promoting EU ideas on YouTube and other video-sharing platforms. One of the most popular of these explores parallels with the work of the cult hero, Nikola Tesla (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akM9KNEv_JE). David is also known as The Soupdragon.

Ideas and/or concepts presented in Thunderblogs do not necessarily express or represent the Electric Universe Model of Cosmology or the views of The Thunderbolts Project or T-Bolts Group Inc.