July 24, 2020

Ganymede is the largest moon.

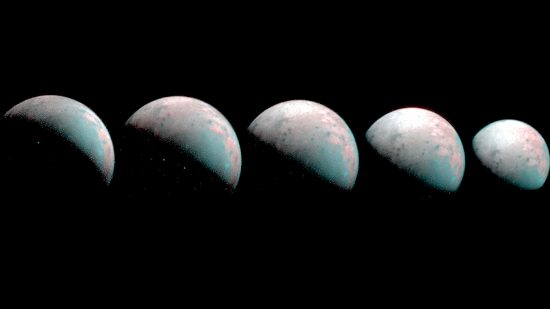

Beginning with Pioneer 10 in 1973, and including the most recent visit by Juno, Jupiter and its moons continue to be the subject of deep space missions. Over the last four decades, eight different spacecraft have flown past the planet and many of its moons. Of them all, Ganymede is possibly the most exotic, with a wild mix of topography, fractures, craters and rilles.

Ganymede is unique because it possesses an intrinsic magnetic field; something not even found on Mars. In December 1995, the Galileo spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter. During a flyby of Ganymede at an altitude of only 838 kilometers, Galileo discovered a dipole magnetic field similar to the one surrounding Earth. The signature of Ganymede’s electric flux tube (the electric current that connects it with Jupiter) can be seen in Jupiter’s polar aurora.

With a mean diameter of 5262 kilometers, Ganymede is the largest moon in the Solar System, and is the fourth largest rocky object after the planet Mars. Ganymede’s core is thought to be too hot to hold on to permanent magnetism. On the other hand, Ganymede is so small that, according to conventional astrogeology, it should have cooled off billions of years ago and not have a liquid core in the first place.

Astrophysicists speculate that Ganymede may once have been much closer to Jupiter, so it was alternately compressed and stretched by “tidal forces”. The constant kneading of the moon kept its core liquid for much longer than if it had formed in its present orbit. If that was the case, then a new problem arises: what forced an object bigger than the planet Mercury to move into a new orbit? What mechanism forced several quintillion tons of rock thousands of kilometers against the force of Jupiter’s gravity?

The most obvious aspect of Ganymede’s bizarre nature are the manifold examples of electric discharges. A gigantic circular structure dominates an entire hemisphere, with several bright craters arrayed in a spiral. Directly below the circular depression are two other unusual craters, looking like twin craters found on Mars. Some craters have rays extending outward for several kilometers. Several have one or more nested concentrically. Those features require unlikely coincidences if mechanical impacts are to explain them, but EDM creates such scars naturally

Could Ganymede’s electromagnetic field be related to the electrical phenomena that scarred and transmogrified it? If Ganymede was indeed closer to Jupiter at some point in its past, then wrenched from orbit and thrown thousands of kilometers farther out from the tidal grasp of its parent, could the force that was responsible for that event be electrical in nature? Was the moon gripped by an electrodynamic field large enough to imprint its core with permanent magnetism? What effect does the electrical connection with Jupiter have on Ganymede today?

ESA plans more missions to the moons of Jupiter in the next ten years. As more data is returned from a growing number of deep space probes, perhaps it will help to increase awareness for electricity in space.

Stephen Smith

The Thunderbolts Picture of the Day is generously supported by the Mainwaring Archive Foundation.