July 22, 2020

High temperatures in galaxy clusters are an enigma, because astronomers have only one force in their bag of tricks: gravity.

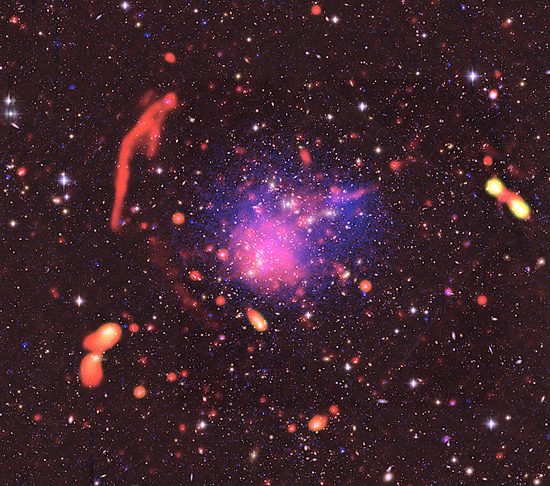

Whenever energetic events are found in deep space, like high temperatures in galaxy clusters, it “must be” caused by a gravity-driven collision in the remote past. Electric charge is sometimes mentioned, but it is usually said to be negligible in its effect, if it has any effect at all. In visible light, there is a serene, undisturbed galaxy cluster. In X-ray frequencies, temperatures over 70 million Kelvin exist where two clusters are thought to be colliding.

Astronomers believe that plasma is ionized gas, behaving according to physical laws that apply to neutral matter. They cannot measure the properties of extragalactic space, directly, so they develop mathematical models based on the behavior of neutral gases. Hannes Alfvén, in his monograph, Cosmic Plasma, described how theory has lost touch with reality. He, on the other hand, studied its properties in the laboratory.

In previous Picture of the Day articles, it was noted that charged particles streaming from stars like the Sun are called a “wind” by the majority, instead of an electric current. Ions accelerated by magnetic fields are referred to as “jets”, instead of the collimated transmission of electrical energy through space. Changes in the density and speed of charged particles are almost always deemed to be “shock waves”, and not the mark of double layers that can store and dissipate electricity, or even explode.

In the consensus view, Abell 2744 is thought to be incredibly hot because molecules of gas and dust “crash into each other”, resulting in X-rays flashing out from the blue color-coded regions. Computer simulations assure astrophysicists that what is unobservable “billions of light-years” away can be modeled on the desktop. It is not surprising, therefore, that observations appear to match the simulations. The ideas used to build computer algorithms are also in the minds of those working with the instruments. Building a device that is designed to see what has been simulated is how modern science works. Carts and horses come to mind.

A lack of knowledge about electricity in space can account for the opinion that gases “crashing into each other” produce X-rays and other energetic emissions. Since perception comes from training and education, without exposure to theories about the behavior of electricity flowing through plasma no perception of it can exist in the mind’s eye.

Among the many differences between plasma and models based on neutral gas are temperature anomalies like the ones seen in various galaxy clusters: temperatures are 10 to 100 times higher than expected. So, from an Electric Universe point of view, anomalous temperatures are a normal property of plasma interaction between clusters.

Alfvén wrote:

“The cosmical plasma physics of today . . .is to some extent the playground of theoreticians who have never seen a plasma in a laboratory. Many of them still believe in formulas which we know from laboratory experiments to be wrong . . . several of the basic concepts on which theories of cosmical plasmas are founded are not applicable to the condition prevailing in the cosmos. They are ‘generally accepted’ by most theoreticians, they are developed with the most sophisticated mathematical methods; and it is only the plasma itself which does not ‘understand’ how beautiful the theories are and absolutely refuses to obey them. . .”

As written many times in the past, Birkeland currents are electromagnetic filaments that carry electric charges through space. The filaments isolate regions of opposite charge and prevent them from neutralizing. Almost every body in the Universe displays some kind of filamentation. Since the various loads in galactic circuits radiate energy, they must be powered by coupling with larger circuits. How large those circuits are can be inferred by the observation that galaxies occur in strings, and are also joined together by filaments.

Two of the most pressing issues in the modern approach to understanding the Universe are the adherence to redshift as the only tool for estimating distances and ages of stars and galaxies, and a lack of knowledge when it comes to electricity. For this reason, while the consensus scientific worldview only permits isolated galactic “islands” in space, the Electric Universe hypothesis emphasizes connectivity with a vast network of electrically active “transmission lines.” That spatial wiring is composed of Birkeland currents.

Stephen Smith

The Thunderbolts Picture of the Day is generously supported by the Mainwaring Archive Foundation.