April 23, 2020

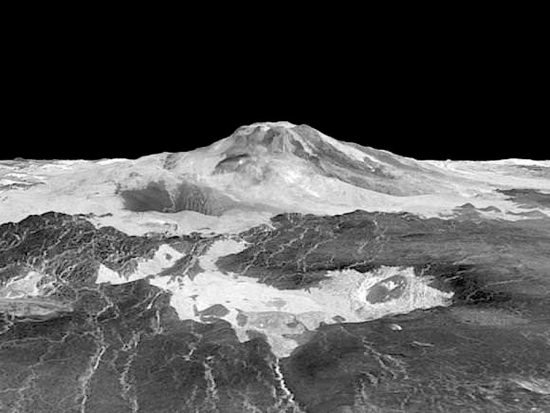

A new mission to study the second planet.

The European Space Agency’s Venus Express mission is now over. Launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on November 9, 2005 the spacecraft entered orbit around Venus on April 11, 2006. Sometime in November 2021, NASA will launch the DAVINCI mission, or Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging, with arrival at Venus in June of 2023.

DAVINCI will encounter Venus four months after launch, so that it can establish a landing target. When it arrives back at Venus 15 months later, the lander will be released on a two-parachute system. According to mission parameters, “…DAVINCI has no requirement to survive touchdown; however, the descent sphere carries sufficient resources (e.g., power, thermal control) to continue science operations and data relay for ~17 minutes on the surface.”

In a previous Picture of the Day, it was noted that the optical spectrum of Venus resembles a gas discharge tube similar to a neon lamp. Astrophysicists are unable to explain the contradictions that inevitably result when trying to explain the data based on greenhouses and smog, but an electrical explanation covers all the bases.

The atmospheric composition of Venus seems to require the presence of intense lightning in order to form the sulfurous compounds that are present. No “normal” chemistry on Earth or Venus can explain the depth and density of the sulfuric acid clouds and abundant carbon dioxide.

Since Venus radiates twice the energy it receives from the Sun, there must be a source for that heat. Venus has an extremely weak magnetic field and no magnetosphere, but it does possess an ionosphere, so it is an electrically charged body. Its ionospheric charge flow carries electricity from the solar wind into the Venusian environment. It could be that the planet is constantly charging and discharging in the infrared, which would generate heat.

One of the “surprising” discoveries from Venus Express was electric discharges in the planet’s upper atmosphere. The discovery was completely unexpected because the density of the Venusian atmosphere was thought to prevent the formation of lightning bolts. Venus is not really separate from the Sun, but acts as an element in the vast electrical circuit that powers the Solar System. The observational data, coupled with ideas put forth by such luminaries as Irving Langmuir and Hannes Alfvén, proves that lightning on Venus was both expected and predicted by Electric Universe advocates.

Venus Express found low-frequency electromagnetic radiation in bursts lasting fractions of a second. Called “whistlers”, the bursts are considered a sure sign of electrical phenomena. A whistler is an extremely low-frequency electro-acoustic wave that is normally generated by lightning. They are called whistlers because they demonstrate a characteristically decreasing frequency falloff in detection equipment. In some short-wave radio transmissions, the whistle can be heard while tuning between stations. Whistlers were the first definitive evidence of lightning on Venus.

DAVINCI will attempt to confirm those observations during its descent phase.

Stephen Smith

The Thunderbolts Picture of the Day is generously supported by the Mainwaring Archive Foundation.