Jan 29, 2019

Planetary nebulae sometimes reveal bifurcated jets emanating from their interior stars. More often than not, those jets reveal an indication of helical shapes.

Common astronomical theories propose that red giant stars expand because they “burn” most of their primordial hydrogen, and begin consuming the helium that was created in thermonuclear fusion reactions. As the theory states, stellar hydrogen fuses into helium; helium then sinks into the stellar core because of its greater atomic weight, accumulating over millions, if not billions, of years.

When a star uses up its hydrogen, it contracts because interior radiation pressure can no longer overcome the gravitational forces that are constantly trying to pull the star’s outer layers into its core. As compression continues, internal pressure rises and heats up the star, until temperatures are great enough to fuse helium into carbon. The star expands into the red giant phase so that it can increase its surface area and radiate away helium fusion energy.

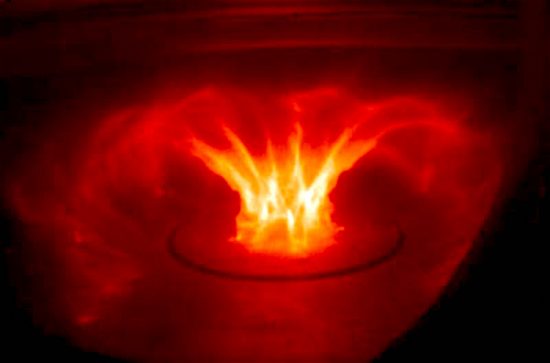

After a star can no longer fuse ever heavier elements, the current model of stellar evolution says that it will shed its outer layers, exposing its hot, dense core, and gradually become a white dwarf. As a star changes with age, large amounts of glowing dust and gas surround it, forming braided streamers and helical “tornadoes” in space, otherwise known to Electric Universe theorists as Birkeland currents.

Electric discharges in plasma create field-aligned magnetic sheaths. Those discharges cause the sheaths to glow, sometimes creating a number of other sheaths. Those space-charge sheaths are known as “double layers”. Positive charges build up in one region of a plasma cloud and negative charges build up nearby. An electric field develops between the two regions, accelerating charged particles to high velocities. Those electric charges spiral in electromagnetic fields, emitting X-rays, extreme ultraviolet, and sometimes gamma rays.

As mentioned, double layers glow, revealing distinct boundaries between sheaths. Since electric charge flows along the sheaths, the Birkeland currents attract each other over cosmic distances. However, because of like charge repulsion, they do not merge. Rather than coalescing, they wind around each other, ultimately growing into long electric “transmission lines” in space. Planetary nebulae, therefore, should be thought of as gas discharge tubes that are many light-years long.

Planetary nebulae are thought to be sustained by explosive shock waves traveling through gas clouds. Since kinetic events are largely chaotic, their emissions should exhibit multiple spectrographic signatures. Instead, over 90% of their light occurs over a small range of frequencies, mostly from ionized oxygen.

Retired Professor of Electrical Engineering, Dr. Donald Scott, author of The Electric Sky, wrote about the way plasma acts in the Universe:

“Plasma phenomena are scalable. Their electrical and physical properties remain the same, independent of the size of the plasma…In other words we can make accurate models of cosmic scale plasma behavior in the lab, and generate effects that mimic those observed in space…Electric currents flowing in plasmas produce most of the observed astronomical phenomena that remain inexplicable if we assume gravity and magnetism to be the only forces at work.”

Stephen Smith