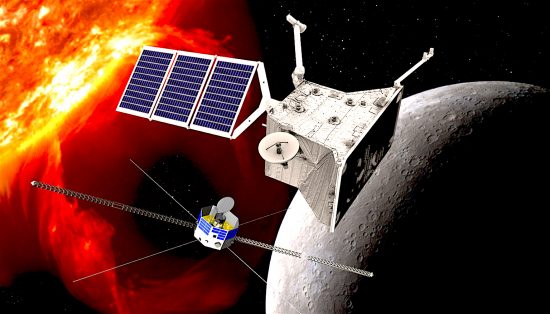

Artist’s impression of BepiColombo. Credit: ESA.

Jan 3, 2018

Mercury is in the crosshairs.

In October 2018, a joint mission to Mercury will be launched. The BepiColombo mission is named after Giuseppe (Bepi) Colombo (1920-1984) from the University of Padua, Italy. As the mission highlights page indicates, Colombo was the first to understand that Mercury’s rotation on its axis three times for every two orbits around the Sun was due to a resonance between the two bodies. The mission will consist of two satellites: the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO). MPO is designed to study Mercury’s composition, while MMO will study Mercury’s magnetosphere.

BepiColombo will be sent into an Earth-trailing orbit. After a year and a half, it will catch-up to Earth, where a gravity-boost will deflect it toward Venus. Since BepiColombo must decelerate as it approaches the Sun, two Venus flybys and six Mercury flybys will lower its relative velocity until Mercury captures it on December 5, 2025.

The last mission to Mercury ended in 2015, when the MESSENGER spacecraft was deliberately crashed into the planet’s surface after it ran out of maneuvering fuel. It found that Mercury, like most bodies in the Solar System, possesses a weak magnetic field, but how it is generated remains a mystery. Modern theories use ideas about Earth and transfer them onto Mercury. So, planetary scientists think that a rotating “dynamo” of molten metal exists inside Mercury, although Mercury ought to be a dead world—the molten interior should have cooled off eons ago.

MESSENGER confirmed many things about Mercury. It is a small planet, only 4878 kilometers in diameter, meaning the moons Ganymede and Titan are both larger. Mercury revolves at a mean distance of 57,910,000 kilometers from the Sun, so a year on Mercury lasts 88 days. Since it rotates once every 58.6 days, the planet completes three rotations for every two orbits.

Mercury is thought to be around 75% iron, with a thin, silicon-rich crust. Consensus theories cannot explain the abundance of iron, since the ratio of iron to silicon is opposite that of the other rocky planets. Another puzzle that BepiColombo will investigate is Mercury’s thin atmosphere. Temperatures exceed 400 Celsius at noon, and the planet is blasted with nine times more radiation than Earth, so how can it possess a detectable atmosphere?

A planet with a gravity field only 38% that of Earth, with such intense solar irradiation, should not exhibit even the smallest atmospheric remnant. In the Electric Universe view, it is possible that Mercury is a young planet, so, like Titan (a possibly young moon of Saturn), it retains some of its primordial envelope, despite low gravity.

A previous Picture of the Day proposed that celestial bodies like Mercury should not be thought of as geriatric denizens of a wizened Solar System. Rather, given the anomalies, it would be more appropriate to think of them as youthful members of a dynamic ensemble. Mercury is probably a young planet, possibly achieving its present orbit within the last 10,000 years. If that is true, there might have been a period in Mercury’s history when the surface was the scene of gigantic electric discharges pulling out craters, cutting vast chasms, and rearranging the atomic structure of the planet’s crust over large areas. Given those circumstances, no theories about Mercury will stand unless electricity is given its due.

Stephen Smith