Sep 19, 2014

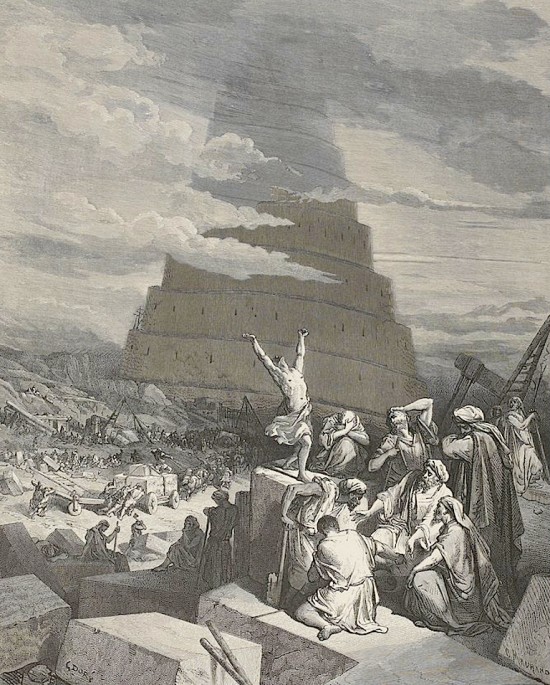

From a comparative viewpoint, perhaps the most common ‘contaminations’ in mythological data are distorted echoes of the Hebrew myths of paradise, Noah’s flood and the tower of Babel, conveyed to exotic societies by Christian missionaries.

Similar to stratigraphical clues in archaeological excavations, elements of language, style and composition can provide a dead giveaway of Biblical influence. Concentrating on the Babel story, examples are the direct speeches of unanimous exhortation within the group, as in this account from the Pare people (northern Tanzania):

‘God was still close to them. But when the people multiplied, they became defiant and spoke to each other: ‘Well then, let us build a tower, the crest of which will reach into the upper land, so that we can creep up and bring war into the land of the one up there.’ But Kyumbi looked down upon them, just like a human being looks down upon an army of ants, and said: ‘What kind of vintu are these, what midgets down there?’ Then he provoked an earthquake, the tower split asunder in the middle and buried the builders in its débris. But Kyumbi withdrew the upper land and since then Kyumbi is no longer close-by, but infinitely far.’

Yet even if exposure to missionary tuition seems undeniable, researchers reaching for the sky rarely arrive at a straightforward answer to the question of origin. Perhaps more often than not, a few new style elements were grafted onto earlier original traditions. The existence of an authentic native Pare tale may be inferred from the overt belligerence of the builders, the earthquake and the resultant lifting of the sky as motifs foreign to Genesis, the absence of a ‘confusion of tongues’ and the existence of parallel myths with variants in adjacent areas. To illustrate the latter, the Nyamwezi (central Tanzania) relayed this tale of the ‘tower building of the Valengo’:

‘In the beginning lived the Valengo. They were one big family, dwelled in a gigantic city and had one language. One day they said to each other: Come on, let us build a high tower and ascend to the sky in order to fetch water! All Valengo agreed and they immediately commenced to build. They built for many months, until they were close to the sky. … Tomorrow we will enter the sky, because the tower reaches until the sky. All approved. The next morning they mounted the tower. But because they were close to the sky, they saw a very large wind coming. Then the tower broke asunder in the middle and all Valengo died, without leaving any offspring.’

In this case, the phraseology and the reference to a single primordial language suggest a partial dependence on Judaeo-Christian sources, but the protagonists’ motivation and the involvement of wind are alien to Biblical scripture. Again, the tradition of Hao and Makemo (Tuamotu, Polynesia) concerning what transpired after the deluge exhibits unmistakable Christian overtones: ‘At the time of the construction of the enclosure at Maragai, in the land Havaiki, we at that ancient time had only one language; but our ancestors having told us about building the enclosure in order to arrive at the sky above and see Vatea, this one, enraged, broke the enclosure, cast out all those who built it and then changed their language …’

Nevertheless, the responsible ethnographer, the French Eugène Caillot (1866-1938), observed that this tradition was expressed in highly archaic locution and that the islanders claimed to have received it from their ancestors prior to the arrival of Europeans. The English anthropologist Robert Wood Williamson (1856-1932) concurred: “I point out that in Polynesia a tradition may be in the main of truly native origin, even if biblical matter has been inserted into it.”

Rens Van Der Sluijs