A ‘box of daylight raven hat’ (lkaayaak yeil s’aaxw), depicting the wily raven in the act of releasing the Sun (the red disk with an inlaid mirror), the Moon and the stars from his grandfather’s box, which he clutches in his hands (c. 1850 CE) from the Gaanax ádi clan, T’aaku tribe Tlingit Nation, Northwestern British Columbia, Canada). © Marinus Anthony Van Der Sluijs. Courtesy Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, Washington, United States of America.

May 20, 2013

The story of the ‘making of the world’ is a global legacy of all traditional cultures.

One of many angles from which it can be approached is an interplay between darkness and light. From an ancient point of view, cosmic ‘creation’ was a protracted ‘dawn’, a gradual transition from primordial darkness to the alternation of day and night as we know it, progressing by leaps and bounds.

Anomalous episodes in this process – such as a lasting ‘night’, a time when the sun was ‘too close’ or ‘too hot’, and a perpetual day – are staples of world mythology, but benighted mythologists often denied such ‘damned data’ from seeing the light of day; they languish in the archives, understudied.

One theme that was rarely even noticed concerns a period of erratic daylight. For example, the Unalirmiut group of the Central Alaskan Yup’ik related that the creator, Tu-lu´-kan-gûk (‘Raven Father’), caused an initial period of prolonged continuous darkness, followed by a time of intermittent episodes of sunlight:

‘So he went away and, taking the sun, put it into his skin bag and carried it far away to a part of the sky land where his parents lived, and it became very dark on earth. … The people on earth were very much frightened when the sun was taken away, and tried to get it back by offering Raven rich presents of food and furs, but without effect. After many trials the people propitiated Raven so that he let them have the light for a short time. Then he would hold up the sun in one hand for two days at a time, so that the people could hunt and get food, after which it would be taken away and all would become dark. After this a long time would pass and it required many offerings before he would let them have light again. This was repeated many times.’

The Ute (primarily Utah and Colorado) agreed that Ta-vi, ‘the sun-god’, had originally been capricious: ‘In that long ago, … the sun roamed the earth at will. When he came too near with his fierce heat the people were scorched, and when he hid away in his cave for a long time, too idle to come forth, the night was long and the earth cold.’ At such times, living beings would often be ‘anxiously waiting for the return of Ta-vi, the wayward sun-god.’ This was before the gods ‘established the days and the nights, the seasons and the years, with the length thereof, and the sun was condemned to travel across the firmament by the same trail day after day till the end of time’.

And on Manihiki (northern Cook Islands, Polynesia) it was the former rapidity of the sun’s movement that lingered in memory:

‘In those days the Sun travelled so fast that his light disappeared before men could get their food cooked. Maui resolved to noose the Sun, but all his ropes were burnt up by the Sun’s fierce heat, until at last he plaited a rope made from tresses of hair of his sister Ina. With this bond he stayed the course of the Sun until amendment was promised by the god of light.’

What to make of such puzzling reports? In the cold light of day, the regularity with which they appear, with their contexts, suggests that they commemorate a genuine environmental condition of some sort.

Changes in earth’s orbital movement naturally spring to mind. Could alterations in the earth’s spin rate, axial tilt and eccentricity, or the shape, diameter, speed and even direction of its orbit account for traditions of longer and shorter days? This cannot be ruled out in theory, but because mutations of that kind affect the earth as a whole it imposes tight constraints on the geographic distribution and internal consistency of pertinent traditions – which will need to be identified and tested.

Sunlight, like all celestial sources of light, is filtered through the earth’s atmosphere. Which frequencies of light and other electromagnetic waves are given the green light depends on the plasma frequency and the chemical composition of the atmosphere – complex physics with many enigmas still awaiting resolution. The varying albedo or reflectivity of other planets, and fluctuations such as the ‘polar brightening event’ which befell Venus in early 2007, serve as a valuable ‘space laboratory’. Perhaps comparative planetology will one day illuminate how the earth’s atmosphere, too, could in the past have passed through stages of opacity – permanent or intermittent, disrupting the ordinary cycle of day and night.

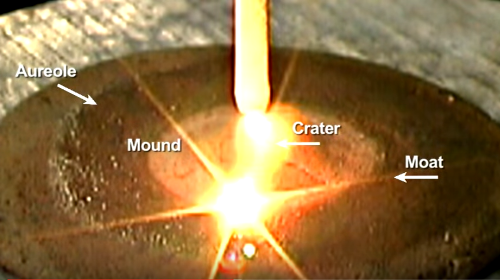

A third lead reflects on the possibility that the ‘fickle suns’ of human tradition referenced not necessarily the actual sun, but other radiant atmospheric or celestial objects. Anthony Peratt’s hypothesis of an intense-auroral z-pinch features a set of ‘plasmoids’ contained within the hollow sheaths of a sustained plasma column, which emitted exceedingly bright synchrotron radiation light. Varying plasma parameters would have produced fitful antics – causing the plasmoids to switch on and off at unpredictable times, just as in the myths.

If ionospheric or magnetospheric plasmoids of this kind materialised for a time as temporary ‘suns’, light is shed on various related mythological themes as well: that such ‘suns’ could be multiple; that they could be stationary, perhaps enclosed in a ‘box’ comparable to a surrounding plasma sheath; that they could be ‘low’ in unison with an entire low-hanging ‘sky’; that they could have strings attached, snares set by mythical heroes which might really be localised aurorae exposing magnetospheric field structure; that the proper regulation of the sun and the moon was only enabled by the ‘separation of sky and earth’; and so on. Moreover, such pseudosolar plasmoids could have occurred at different places at different times, allowing greater variability between the respective traditions.

The sheer complexity of all these scenarios is almost forbidding. All three lines of inquiry seem to have played some part in the bewildering phenomenology of ‘creation’ events. Will we ever see the day that the pieces of the puzzle can all be identified and matched?

Rens Van Der Sluijs

Books by Rens Van Der Sluijs:

Traditional Cosmology: The Global Mythology of Cosmic Creation and Destruction

Volume One: Preliminaries Formation