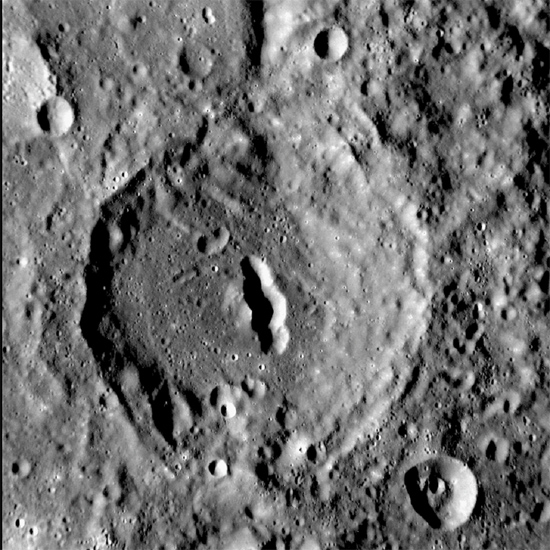

Unnamed “pit-floor crater” on Mercury. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Smithsonian Institution/Carnegie Institution of Washington

Oct 10, 2012

Rather than volcanic vents, pits in craters could be a sign of electrical activity.

On August 3, 2004, NASA launched the Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) experiment from the Cape Canaveral facility on a 7-year mission to study the Solar System’s innermost planet.

The last spacecraft to explore Mercury was Mariner 10 during its tour of it and Venus. Mariner 10 flew near Mercury in 1974 – March 29, September 21 and then again on March 16, 1975. However, because there was no orbital insertion, only about 45% of the surface was mapped by the onboard instruments. Because MESSENGER is orbiting Mercury, mission specialists hope to find answers to other mysteries left unanswered for the last 34 years.

The geology of Mercury is intriguing to space scientists because it provides them with a number of “mysteries” and “processes that have yet to be understood.” Complex chains of craters and melted pits extend outward from terraced depressions over 60 kilometers wide. The flat bottoms and the vertical sidewalls have been presented in past Picture of the Day articles as signs that they were created through electric discharge machining (EDM) and not because of meteor impacts on the surface.

Although the surface of Mercury is usually taken to be an example of the “bombardment by meteorites” theory, the signs of EDM are more prevalent than the signs of kinetic shock through the strata. Most of the debris on the surface of Mercury appears to be chunks of fallback material that was blown out by the explosive energies of plasma discharges. Ordinarily, as in the image at the top of the page, the craters have little if any ejecta surrounding them. The crater field shown above is generally lacking in boulders or smaller breccias despite the surrounding haloes of blackened terrain.

A magnetometer on the satellite should help resolve where Mercury’s weak magnetic field is coming from. Modern theories suggest that a rotating “dynamo” of molten metal exists inside Earth and that is how our magnetic field is created. Mercury is thought to have a molten outer core, as well, but no one knows if it is working like Earth does or if the field is part of the crust, like Mars. No one understands how a molten core exists on Mercury since the planet appears cold and dead. The molten interior should have cooled off eons ago.

Another theory suggests that Mercury’s slow rotation keeps the magnetic field in a weakened state. Mercury rotates in 59 Earth days, making it the planet with the slowest rotation next to Venus. It is more likely that the problematic “dynamo theory” of planetary magnetism is wrong. According to Electric Universe physicist Wal Thornhill, a slowly rotating charged body will produce a weak dipole magnetic field.

NASA scientists often refer to what they find on Mercury and other planets as “mysterious” or “puzzling” with long years of research and contemplation ahead of them. We predict that the reason for the confusion is the problem of reverse application. Earth should not be used to explain the Solar System. The geological patterns found elsewhere deserve alternative viewpoints.

Stephen Smith