Not If, But When: Cosmology in Crisis

& The Coming Paradigm Shift, Part 1

by Dr. Ghada Chehade

I want to stress from the outset that my background is not in the physical or natural sciences. As a political scientist and discourse analyst, I am interested in the broader cultural impacts of science, and cosmology in particular. For this reason, I do not debate science in these articles; I am not qualified to and will leave it to actual scientists to debate scientific truths. When dealing with cosmology and astrophysics, I rely heavily on direct quotes by scientists and/or scientific publications and videos. My main focus, and main interest, is cosmology’s impact and function beyond the sciences.

With respect to cosmology’s broader impact, as I have stated in a previous article, think for a moment about what a significant and defining field cosmology is. Historically speaking, cosmology can be seen as the mother of all science and philosophy. Cosmology tells the “big story” of our universe and deals with the big questions. Fundamentally, cosmology tells the story of what is.

What is this thing we call the universe? What is the structure of the universe? What is its driving force? How and why did it develop the way it has? Also, is it isolated or is it connected, is it finite or is it infinite, does it have an origin, does it have an end . . . ?

These questions are as much philosophical as they are scientific, and therefore have impact far beyond the sciences. To put it simply, just thinking about the universe will eventually lead to contemplating everything within it.

As a discipline, cosmology can be defined as “the scientific study of what the Universe is made of, where it came from, how it came to be the way it is today, and what its future holds.” 1 For over 100 years, the Big Bang theory has been the dominant model/paradigm within cosmology; it has told the story of the cosmos and informed our understanding of it. Albert Einstein’s theories are integral to—and indeed engendered—the big bang theory. As NASA (2005) explains: “Einstein’s theories about light, motion, gravity, mass and energy began a new era of science. They led to the big bang theory of how the universe was born. And they led to concepts such as black holes and dark energy.” 2

Cosmology’s Broader Impact

While Einstein’s theories shaped our present-day cosmology (and astrophysics), his impact was much broader: “Einstein’s theories of relativity have not only affected our daily lives in such basic ways as how we heat our homes, reach our destinations, and measure our days.” 3 It has been noted that “Albert Einstein’s impact on the world was so immense that any assessment must range beyond the sciences to take in the multifarious ways he changed culture.” 4 As a social scientist and political scientist, I am especially interested in this broader socio-cultural impact.

For better or worse, Einstein’s theories—especially his Theory of Relativity—have greatly impacted art, philosophy, and modern culture. It is important to point out that Einstein did not personally apply his theories to any of these things. Rather, his theories were taken out of their scientific context and applied by thinkers in the non-sciences (mainly in the Humanities and Social Sciences). In the world of art, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity contributed to the revolutionary departure from representational art and the rise of abstract art. Most notably, Einstein’s Theory of Relativity contributed to the development of cubism, a style established by Picasso and his colleague Georges Bracque: “In Cubist artwork, objects were analyzed, broken up, and reassembled in an abstracted form instead of being depicted from one viewpoint.” Cubists “depicted subjects from a multitude of viewpoints to create a greater scope of context.” Cubism is considered the most influential art movement of the twentieth century5 and is the cornerstone of the modernist/abstract art movement.

While the modernist abstract art movement has been en vogue for over a century, some see it as the death of art. Writing for the Art Renewal Center, Fred Ross argues that “just because something causes one to have a feeling of aesthetic beauty does not make it a work of art.” For Ross, “a work of art is the selective recreation of reality for the purpose of communicating some aspect of what it means to be human or how we perceive the world.” 6 Abstract art, as defined by modernists, tends to be intentionally meaningless and often intentionally ugly, Ross maintains.

For modernists, “abstract means that which does not have any meaning outside of itself. From the modern critic’s point of view, the more meaningless it is (i.e., the more ‘abstract’) the better.” This is not to say that “abstract” shapes or blobs of paint cannot be aesthetically pleasing. Ross stresses that they can. But he concludes that they cannot be meaningful in any real sense: “It is whatever it is, a blob of paint or a block of color — no more and no less.” 7 Similar criticisms have been lauded against modern poetry, which has also been influenced by relativity and abstraction. Some see modern poetry as non-poetic writing for its own sake, devoid of meaning, meter, rhythm or rhyme.8 Whatever one’s opinion on the modernist abstract movement, there is no denying that Einstein’s concept of relativity greatly influenced the trajectory of modern art.

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity has also shaped the worlds of philosophy, politics and political activism. As Hans Arora explains, Einstein’s theories of relativity changed the very way we think about morality. His theories “. . . were used by philosophers, politicians, and activists to turn moral philosophy upside-down.” 9 Specifically, relativity fueled postmodernism and philosophic relativism. This new school of thought turned morality on its head:

“Prior to relativity, philosophers such as Aristotle, Kant, and Mill argued that there was an absolute truth and an absolute way of approaching various aspects of life. For example, a businessman who comes across a child drowning in a pond is obligated to save the child’s life. However, now armed with relativity, facts are no longer absolute, but instead dependent upon your viewpoint, your own ‘philosophical’ inertial reference frame.”

This meant that—under relativity-inspired postmodern philosophy—right and wrong now varied from person-to-person, an idea that was readily accepted because it meant that each individuals’ viewpoints could be considered valid, “as there was no absolute truth to be had.” 10 Arora points out that this philosophical argument is not always accepted by the laws and social norms we produce. But in the worlds of philosophy, academia, politics and political activism, relativism—and the notion of infinite individual truths—became all-the-rage and remain so till this day.

While this may be viewed as liberating; not least because powerful forces no longer have a monopoly on morality or truth. The flip side is also true: If there is no such thing as absolute right and wrong, then we are powerless to point out and confront the wrongs of those with power (be it political power, corporate power, etc.), since “everything is relative.” In other words, arguing that there is no such thing as absolute right and wrong alleviates wrong doers—big or small—from responsibility and accountably for wrong-doing.

Beyond morality, an endless array of “valid viewpoints” could lead to socio-cultural chaos and divisions. Societies require some level of cohesion and consensus to function. Relativism run amok could pave the way for a society where individuals are either pitted against one another, or, are too fixated on differences to appreciate their common humanity, common interests and common struggles, or a bit of both. Some may argue that we are already there. One example is the growing divisions over race in the United States. While racism is real and must be addressed at all levels of society, there is little benefit from a country divided. With more and more people in the United States suffering economically, across all racial lines, one has to wonder if there is some degree of “divide and conquer” or “divide and distract” at play. While this is beyond the scope of this article, I have written widely about these matters elsewhere.11

With respect to political activism, postmodern theory—which is informed and influenced by relativity and relativism—moved political mobilization from a focus on the big picture and “the system” (i.e., the politico-economic system and its related and attendant institutions etc.) to a focus on individual or single issues that are often more personal than political. This eventually gave rise to what is known as identity politics, the often apolitical focus on issues related to personal identity and personal feelings (under the mantra that “the personal is political”). As I have demonstrated elsewhere,12 a shift in activism from an emphasis on political or politico-economic issues (such as poverty, labour and workers’ rights, war, civil liberties) to an emphasis on personal identity issues (based on religion, race, gender, sexuality, etc.) contributes to a more divided society that does not recognize its common plight and struggles.13 Historically, it is the power structure (be it political or economic power or both) that benefits from social divisions and tensions.

Overall, these are some of the issues I am interested in as a social scientist and political scientist. But what does any of it have to do with cosmology? For the purpose of this article, the above are good examples of how a theory (relativity) that came out of the world of cosmology and astrophysics specifically, was adopted and applied by non-scientists in ways that would change the entire course of art, philosophy and culture (politics and political activism are a part of culture). While we may not think of these things as being linked to cosmology—and they are not directly linked—it remains true that a theory intended for cosmology and astrophysics—meaning for the world of Science—ended up influencing and impacting the broader culture in profound ways.

When it comes to popular culture, especially the worlds of science fiction and cinema, cosmology’s influence is ever-present. There are hundreds—if not thousands—of science fiction novels and movies that make reference to the Big Bang and its attendant theories and concepts, such as black holes, wormholes, dark matter, singularities, relativity, etc. Some sci-fi shows—especially those that deal with time travel—rely on the Big Bang Theory and its concepts for their entire plot and storyline. A good example is the German Netflix series Dark. And while there are too many to fully list here, some very well-known Big Bang related/dependant films are Star Wars, Planet of the Apes, 12 Monkeys, Contact, Looper, and Interstellar. There is even a massively popular American Sitcom that ran for 12 years entitled The Big Bang Theory.

I could go on and on about relativity’s impact on culture, but I think one gets the general picture. I discussed the non-scientific impacts of Einstein and relativity at great length in order to drive home just how much cosmology impacts the non-sciences or broader culture. If this is the case, then changes in cosmology could also one-day cause changes in the broader culture. To understand how, one must explore the concept of the paradigm shift.

Paradigm Shift

To reiterate, the paragraphs above highlight how cosmology and astrophysics—and the theories and concepts associated with them—greatly impact the broader culture, far beyond the sciences. For over 100 years the cosmological story has been the story of the Big Bang, gravity and relativity. But what if that story is wrong? And what if a new cosmological story, and model, is emerging? What then? How might a change in cosmology and the cosmological narrative impact society and the broader culture?

During my talk at the EU2017 Future Science Thunderbolts Conference I argued that cosmology is the biggest and most definitive paradigm there is and that, as a meta-paradigm, if and when cosmology changes, everything else will also necessarily change. I believe that the when is upon us; a change in cosmology—triggered by a crisis in cosmology—is presently unfolding, and this change constitutes a paradigm shift or scientific revolution (in cosmology).

What Exactly Is A Paradigm Shift?

Paradigm shift is a term we hear a lot these days but many may not know what it means. First, let’s define paradigm. For the purpose of this article, I use the following definition: A paradigm is the dominant theory in any given discipline at any given time.14 And a paradigm shift happens when the dominant theory is replaced by another one.

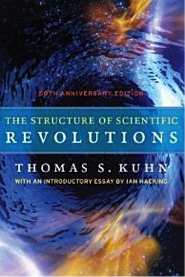

The term paradigm shift was coined by the physicist and philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn, in 1962, in his seminal work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In that book, Kuhn challenged the world’s conception of science at that time, which was “that science was a steady progression of the accumulation of new ideas.” In a brilliant series of reviews of past major scientific advances (such as those ushered in by Galileo, Newton and Einstein) Kuhn showed this viewpoint was wrong. For Kuhn, “science advanced the most by occasional revolutionary explosions of new knowledge, each revolution triggered by introduction of new ways of thought so large they must be called new paradigms.” 15

Simply put, a paradigm shift is scientific change that is forced to happen. An easily understandable example of a paradigm shift “is the transition from the Ptolemaic (geocentric) theory to the Copernican (heliocentric) theory.” It is well known that in the 17th century of Galileo Galilei’s era, “a revolution abruptly occurred from the idea that the Earth is the center of the Universe to a completely different idea or a new paradigm that the Earth revolves around the Sun.” 16 With respect to its impact on science, the material world, and the ways in which it diminished the impact and influence of the Church, the Galilean/Copernican paradigm shift (and later material and scientific changes ushered in by Isaac Newton and his contemporaries) is arguably far more instrumental and transformative than the shift ushered in by Einstein and the Big Bang model. However, I chose to focus on the latter because the Big Bang and relativity constitute the most recent paradigm shift in cosmology, and the one that most people today would be familiar with. It is the Big Bang model (and its attendant theories and concepts) that have dominated cosmology and astrophysics—and the popular imagination—for the last century.

In the next article, I will take a closer look at Thomas Kuhn’s paradigm shift concept, and how it applies to the present state of cosmology.

NOTES

2 https://www.nasa.gov/audience/forstudents/5-8/features/F_Einstein_5-8.html

3 https://helix.northwestern.edu/article/einsteins-theory-relativity-implications-beyond-science

4 http://www.nbcnews.com/id/7406337/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/culture-einstein/#.X2gy1zXZeu5

6 https://www.artrenewal.org/Article/Title/abstract-art-is-not-art

7 Ibid.

8 See https://sevensecularsermons.org/rudyard-kipling-and-exactly-why-modern-poetry-systematically-sucks/

9 https://helix.northwestern.edu/article/einsteins-theory-relativity-implications-beyond-science

10 Ibid.

11 See https://politicalanthropologist.com/2018/04/24/identity-politics-diversion-growing-economic-crisis/

13 See https://soapbox-blog.com/2016/11/18/the-new-left-and-the-limits-of-identity-politics-revisited/

14 https://www.sfu.ca/educ867/htm/paradigm.htm

15 http://www.thwink.org/sustain/glossary/KuhnCycle.htm

16 https://www.ipmu.jp/sites/default/files/webfm/pdfs/news13/E_FEATURE.pdf

Copyright © 2021 Ghada Chehade. All content in this article is the sole property of the author and can only be reproduced with the expressed permission of the author, Ghada Chehade.

Dr. Ghada Chehade is an award-winning writer, social critic and performance poet. She spent over a decade as a political analyst, specializing in geopolitics and the study of socio-political change. Her articles and essays have been published in international publications such as Asia Times, The Political Anthropologist, and The Global Analyst. She recently broadened her focus to include an analysis of how changes in science and cosmology impact the larger culture. Dr. Chehade holds a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science, an MA in Communication Studies and a PhD in Discourse Analysis, from McGill University. Her doctoral research won the award for Best Dissertation from the Canadian Association for the Study of Discourse and Writing and was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Dr. Chehade’s earlier articles on the Electric Universe model can be found at soapbox-blog.com.

Email info@ghadachehade.com

The ideas expressed in Thunderblogs do not necessarily express the views of T-Bolts Group Inc. or The Thunderbolts Project.