home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

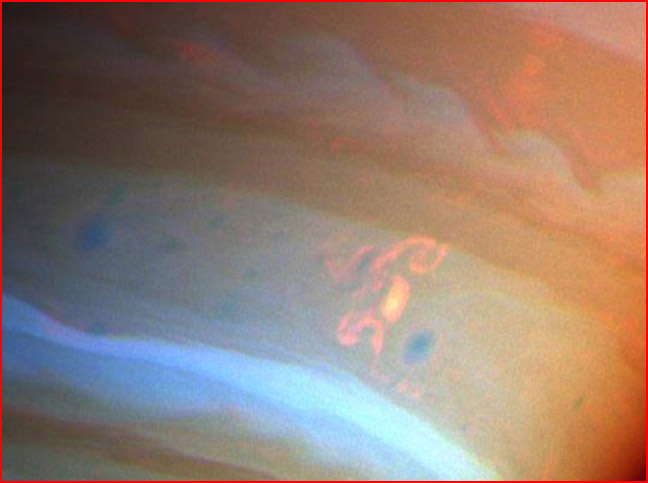

The southern hemisphere of Saturn appears to display twin atmospheric “dragons” around a central vortex.

Credit: NASA/Cassini

Jul 14, 2006

Saturn's Dragon Storm

The mysteries of Saturn’s atmospheric behavior continue to mount as scientists puzzle over a massive "thunderstorm" that has remained fixed in place since it first appeared in 2004.

Most people assume that meteorologists understand the weather. But this is not really so. For instance, if one were to ask a meteorologist what causes lightning on Earth, the only honest answer he or she could give would be, "We're not sure." Dr. Martin Uman, author of numerous books on lightning, takes the conventional view that charge buildup required for lightning comes from vertical movement of droplets in a thundercloud. But he confesses that the process occurs "in a way or ways not yet fully understood."

If meteorologists don’t “fully understand” terrestrial lightning, what are the chances they can explain the “surprise” of lightning on other planets? As Dr. Bill Kurth of the University of Iowa says, " we have some preconceived notions about how lightning works at Earth and we can go to places that don’t have an abundance of water like we have in our atmosphere and if we happen to find lightning there then we have to explain what it is that makes lightning work there if we don’t have water."

In November 1980 and August 1981, two Voyager Spacecraft observed an intense storm near Saturn's equator with high winds (1,100 miles per hour) and continuous lightning. More than twenty years later, in 2004, NASA's Cassini spacecraft spotted an electrical storm with lightning bolts that are 1,000 times stronger than those on Earth. The charged storm was detected in Saturn's southern hemisphere, in the appropriately labeled "storm alley" region. The storm (the size of the continental United States) stretched 2,175 miles from north to south.

The storm presented Cassini scientists with a number of enigmas. It is apparently a long-lived storm that has attached itself to one area and occasionally flares up dramatically. But why one area, which is hardly to be expected if Saturn is a mere ball of liquid and gas? The investigators could not explain why the radio bursts would always start while the Dragon Storm was below the horizon on the night side and end when it was on the dayside. Intriguingly, the Dragon Storm arose in an area of Saturn's atmosphere that had earlier produced large, bright convective storms. Mission scientists concluded, "the Dragon Storm is a giant thunderstorm whose precipitation generates electricity as it does on Earth. The storm may be deriving its energy from Saturn's deep atmosphere."

From an Electric Universe perspective, this conclusion simply repeats the inversion of cause and effect in standard explanations of terrestrial lightning. In the EU model as elaborated by Wallace Thornhill and others, thunderstorms themselves are electric discharge phenomena driven by the circuits that link planets to the Sun and the Sun to the galaxy. (See Thornhill's analysis of the Dragon Storm here.)

It seems inexplicable under a traditional meteorological model that a storm would attach itself to one place (particularly on a planet that is thought not to have a solid surface) and sporadically burst to life. But as noted by Thornhill, “the Electric Universe model of stars and planets provides the possibility of a solid surface on the giant planets. And as we find on Earth, a solid surface allows for regional electrical differences that favor electrical storm activity in one region over another. A good example is ‘tornado alley’ in the southern U.S.A.”

Thornhill describes the twin spiraling formations as miniatures of “spiral galaxies,” and he sees these as “the effects of the interaction of Birkeland current pairs,” just as was demonstrated in the computer simulations of spiral galaxy formation by Anthony Peratt described in an earlier Picture of the Day. If this is so, the megalightning discharges are occurring within the Dragon Storm.

Thornhill argues that the enigmatic switching off of the radio bursts as the storm enters daylight mimics the morning appearance and subsequent fading of the mysterious "spokes," seen occasionally in Saturn's rings. In the EU model, the two phenomena are connected because the spokes are formed by radial discharges to a huge current ring circulating beyond the rings. The discharges travel across the rings at the speed of lightning from the ionosphere, where they draw electrical energy via the storm. The discharges shoot charged ring particles out of the ring plane, in a form of thunderclap, throwing a shadow on the rings. The fading of both the spokes and the storm signals as Saturn rotates into daylight are probably a result of the circuit, which links the morning and evening terminators.

The significance of the storm’s title will not be lost to those familiar with the Thunderbolts group’s exploration of ancient myth and folklore relating to plasma discharge configurations in the ancient sky. Dragon-like monsters soaring across the heavens rank among the most enigmatic and fanciful icons of the ancient cultures. These mythical reptiles come adorned with feathers or wings, sprouting long-flowing hair and fiery, lightning-like emanations. Every detail of such beasts defies naturalistic reasoning. Yet accounts from widely separated cultures attribute many identical features to these biological absurdities.

The spiraling shape of dragons and serpents in mythology and ancient art are strikingly similar to plasma instabilities in the laboratory and in space—all reminding us of the metamorphosing, life-like qualities of plasma phenomena. And it should be no surprise that ancient images of the dragon are intimately associated with the same configurations of electrified plasma that we see in megalightning on Saturn today.

___________________________________________________________________________Please visit our Forum

The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Dwardu Cardona, Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2006: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us