home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

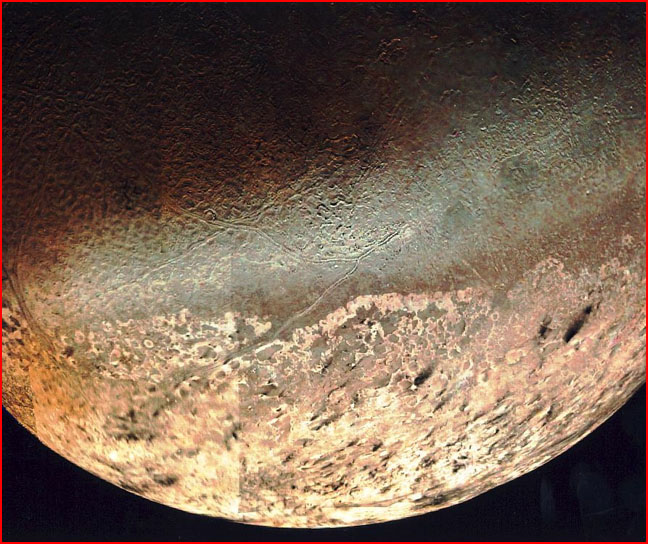

Credit: NASA Voyager 2 Mission

Jun 22, 2007

Triton's "Ice Geysers"Triton, the largest moon of Neptune, exhibits plumes of nitrogen spewing from frozen "geysers" or "cryo-volcanoes" near its south pole. While scientists struggle to comprehend them, analogous plumes and jets elsewhere in the solar system suggest that the answer may be obvious.

On August 20, 1977, NASA launched the Voyager 2 mission on a multi-year journey to the outer solar system. Twelve years after launch, on August 25, 1989, Voyager 2 was the first spacecraft to return close-up images of remote Neptune, now officially recognized as the most distant planet from the Sun (due to the downgrading of Pluto to a Kuiper Belt Object).

One of the greatest surprises of the Voyager mission occurred on the flyby of Neptune’s largest moon, Triton. To the astonishment of planetary scientists, the cameras revealed active geyser-like eruptions spewing nitrogen gas and dark dust particles straight up, eight kilometers into space. The stunned NASA investigators called these eruptions cryogenic “ice volcanoes,” and for almost two decades they have struggled to understand them.

Some theorists have attempted to leverage heat from the Sun into a plausible source of the required energy. Thus, JPL scientists suggested that, “Trapping of solar radiation in a translucent, low-conductivity surface layer (in a solid-state greenhouse)…could provide the required energy.” But others at the University of Hawaii speculated that, “heat released when frozen molecular nitrogen shifts from one crystalline state to another may fuel the geysers.”

Are these exotic proposals really plausible candidates? When Electric Universe proponents hear theoretical guesses of this sort, they see a casual disregard for the patterns of space age discovery. How many unexpected geysers will we have to see in the solar system before planetary scientists begin to ask the obvious questions?

On Triton, several occurrences of geysers were identified in the south polar region. As seen in the picture above the plumes have left behind wind streaks and fan-shaped dark deposits radiating from the point of eruption. The geysers, darkened cavities, and associated streaks are eerily similar to features on Jupiter’s moon Io, which have been cogently explained as electric discharge effects. In a recent Thunderbolts Picture of the Day, we noted the association of highly enigmatic “dalmation spots” and geysers in the south polar region of Mars, and in our continuing series on Martian south polar events we have emphasized the apparent role of charged particle beams excavating ice, and provoking massive geyser activity.

We wrote, “If the dark spotting on Mars’ south polar ice is indeed caused by charged particle streams, one of the first things we should look for is an active response of the surface to these events. Since the dark spotting is occurring in the Martian south polar spring, that would be the time to look for signs of energetic activity--not unlike the so-called “volcanic” plumes of Jupiter’s closest moon Io, or the “geysers” of Saturn’s moon Enceladus.”

NASA scientists, by their disinterest in electricity, have ignored a compelling pattern. When observing events in Neptune’s super frigid domain, they do not even think of Io, or Enceladus, or Mars, because the geologic condition of Triton is so different. They have not realized that these differences pose virtually no issue under an electrical interpretation.

By Stephen Smith

___________________________________________________________________________Please visit our Forum

The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2007: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us