home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

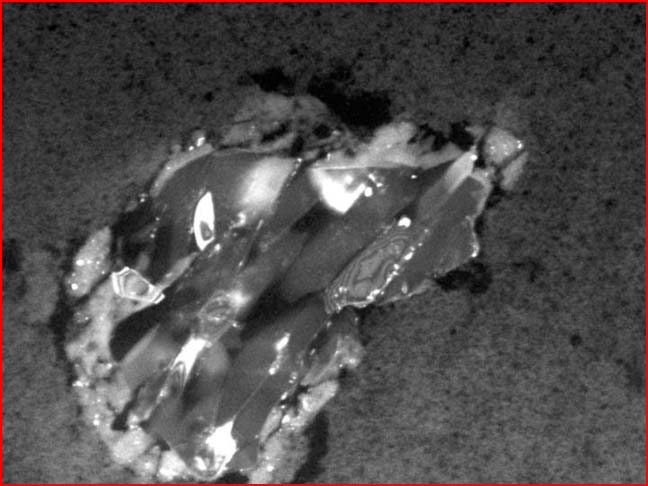

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Washington

This image shows a comet particle collected by the Stardust spacecraft. The

particle is made up of the silicate mineral forsterite, also known as peridot in its gem form.

It is surrounded by a thin rim of melted aerogel, the substance used to collect the comet

dust samples. The particle is about 2 micrometers across.

Mar 16, 2006

“Stardust” Shatters Comet TheoryThe first results from NASA's Stardust mission are in, leaving mission scientists in a state of shock and awe. The tiny fragments of comet dust brought back to Earth did not accrete in the cold of space, but were formed under “astonishingly” high temperatures.

It seems that the gulf between the impressive successes of modern technology and the depressing failure of theory has grown by another giant leap.

NASA’s celebrated Stardust mission was a technical triumph, achieved at a respectable cost. The mission collected the first samples ever of the dust discharged by comets. On January 2, 2004, the Stardust craft had entered the dusty clouds around Comet Wild 2 (pronounced VILT 2), gathering samples of the minute particles as they struck the “aerogel” in a 100-pound capsule. The capsule returned to Earth and parachuted to touchdown on a Utah desert January 15, 2006.

A surprise—the particles revealed abundances of minerals that can only be formed at high temperatures. Mineral inclusions ranged from anorthite, which is made up of calcium, sodium, aluminum and silicate, to diopside, made of calcium magnesium and silicate. Formation of such minerals requires temperatures of thousands of degrees.

How could that be? For decades we have been assured that comets accreted uneventfully from the leftovers of a cold “nebular cloud” in the outermost regions of the solar system. The theoretical assumption has been stated as fact repeatedly in popular scientific media, and its proponents believed it. Indeed, the implication of a fiery past was so unexpected that an early sample of dust was thought to be contamination from the spacecraft.

“How did materials formed by fire end up on the outermost reaches of the solar system, where temperatures are the coldest?” asked Associated Press writer Pam Easton.

"That's a big surprise. People thought comets would just be cold stuff that formed out ... where things are very cold," said NASA curator Michael Zolensky. "It was kind of a shock to not just find one but several of these, which implies they are pretty common in the comet".

Researchers were forced to conclude that the enigmatic particle material formed at a superheated region either close to our Sun, or close to an alien star. “In the coldest part of the solar system we’ve found samples that formed at extremely high temperatures,” said Donald Brownlee, Stardust’s principal investigator at the University of Washington in Seattle, during a Monday press conference. “When these minerals formed they were either red hot or white hot grains, and yet they were collected in a comet, the Siberia of the Solar System.”

Space.com reports that the finding “perplexed Stardust researchers and added a new wrinkle in astronomers’ understanding of how comets, and possibly the Solar System, formed”. But did it really? Paradigms do not die easily. Our own impression is that comet researchers have yet to revisit their “big picture” assumptions. A litany of surprises has not deterred them, and they continue to discuss the formation of comets “at the outermost regions of the solar system”. The idea does not deserve such unyielding devotion. It was never more than a guess, and it never successfully predicted any of the milestone discoveries in cometology.

So the paradoxes and contradictions continue to accumulate. Michael Zolensky, Stardust curator and a mission co-investigator at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC), said astronomers believed that a sort of material “zoning” occurred during the Solar System’s formation. In the eons-long collapse of the primordial “nebular cloud”, material closer to the emerging “sun” formed under hotter conditions, while farther away from the sun everything remained dark and cold. The comet was supposed to be the case par excellence of a body accreted in the outermost region and constituted primarily of water ice and other volatiles.

Speculations erupted. Could it be that something occurred in or very near the Sun in its formative phase, flinging immense quantities of material out to the periphery of the Sun’s domain (far, far beyond the orbit of Pluto), to the “Oort cloud”, the legendary—but never-witnessed—sea of comets?

Then the researchers reminded themselves that this would produce a mixing and contradict the zoning that is evident in the asteroid belt. “If this mixing is occurring, as suggested by these results, then how do you preserve any kind of zoning in the solar system”, Zolenksy asked. “It raises more mysteries.”

Perhaps the paradigm could be redeemed by finding the signature of primordial water, whose existence is essential to the survival of official comet theory.

A report by the journal Nature is illuminating. A writer for the journal spent a day with Phil Bland, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London, as he and his team analyzed part of a grain. When he found large amounts of calcium, Bland was excited. Could the calcium be present in the form of calcium carbonate, a mineral that almost always forms in water? He bet his colleague Matt Genge that this would indeed be the case.

Bland lost the bet, owing Genge a dinner. According to the Nature report NASA “scientists have not yet found any carbonates in their grains”.

Today, the study of comets has reached a crisis. Every key finding comes as a surprise, but no one seems to realize that the surprises are not random— they are predictable under a different perspective. The tragedy is the way inertia can leave well-intentioned scientists with their feet in the sand. The momentum of prior belief, working in concert with pressing demands of funding, creates nearly endless obstructions to open-minded exploration and discourse. Even a brief vacation from an oppressive paradigm could do wonders.

Coming March 17: The Rilles are Electric

Coming March 18: Stardust Shatters Comet Theory (2)

__________________________________________________________________________Please visit our new "Thunderblog" page

Through the initiative of managing editor Dave Smith, we’ve begun the launch of a new

page called Thunderblog. Timely presentations of fact and opinion, with emphasis on

new discoveries and the explanatory power of the Electric Universe."The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITOR:

Michael Armstrong

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Dwardu Cardona, Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Michael Armstrong

Copyright 2006: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us