|

|

|

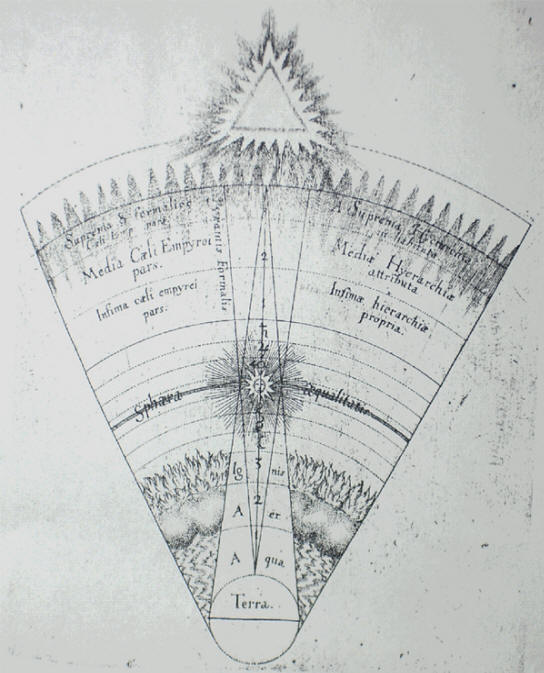

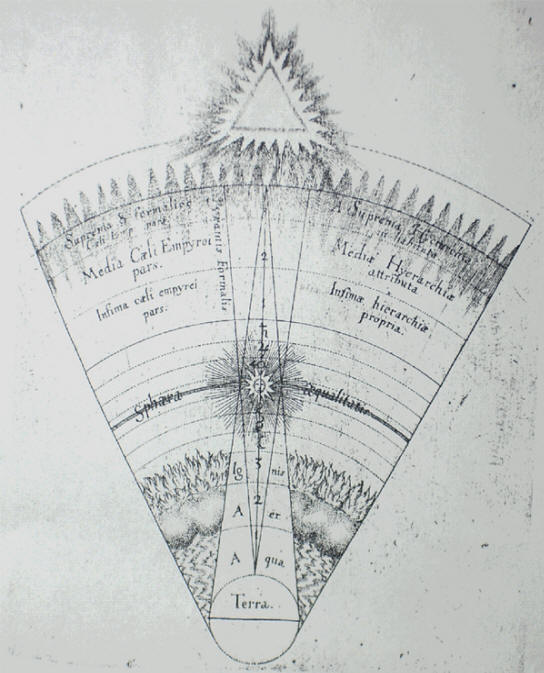

Diagram of the

cosmos designed by the English

physician and alchemist,

Robert Fludd (1574-1637),

Utriusque Cosmi Historia, Ia89).

The sun occupies its characteristic

position midway between

the upper and the lower regions of

the universe.

Light My Fire

Feb 21, 2010

What

powers the sun? Some three

generations of astrophysicists have

perfected the dominant theory that

the sun, like all other stars, is a

giant nuclear fusion reactor,

producing radiation as it converts

hydrogen into helium in its core.

In classical antiquity, philosophers

reflected on the same question, but

often came up with a very different

type of answer: the sun does not

generate its own heat and light, but

draws these from a cosmic

‘powerhouse’. A figurehead of the

Pythagorean movement in his time,

Philolaus of Croton (fifth century

BCE), postulated 'that the sun

receives its fiery and radiant

nature from above, from the

aethereal fire, and transmits the

beams to us through certain pores …'

According to him, 'the sun is

transparent like glass, and … it

receives the reflection of fire in

the universe and transmits to us

both light and warmth …' The Roman

poet, Lucretius (±99-±55 BCE),

similarly accounted for the

remarkable ‘explosion’ of solar

light from one source by comparison

to a fountain, replenished from an

external source:

'Another thing also need not excite

wonder, how it can be that so small

a sun emits so much light, enough to

fill with its flood seas and all

lands and the heavens, and to

suffuse all with warm heat. For it

is possible that from this place is

opened one single fountain of the

whole world, to splash its generous

flood and to fling forth light,

because the elements of heat gather

together from all parts of the world

in such a manner, and their

assemblage flows together in such a

manner, that the heat flows out here

from one single source'.

The cult of the sun god rose to

unprecedented prominence during the

Roman Empire, spawning a rich and

largely unexplored literature on the

sun’s physical and spiritual nature.

Against this background, the notion

that this luminary collects

'elements of heat' from 'all parts

of the world' fired the imagination

of numerous authorities, who, in the

footsteps of Pythagoras and Plato,

regarded the sun and other celestial

bodies as intelligent entities

thriving on a constant influx of a

mysterious concept dubbed ‘the

good’, ‘the intelligible’ or ‘cosmic

soul’ from the highest and outermost

regions of the universe.

That such thinkers did not eschew

metaphysical speculation of this

kind is somewhat understandable

considering that they did not have

today’s accomplished chemistry and

sophisticated tools for observation

at their disposal. It should

certainly not detract from the

intellectual originality of the

notion of an externally powered sun.

Writing in Egypt, the Jewish

allegorist, Philo of Alexandria (20

BCE – 50 CE), reasoned that 'the sun

and the moon, and all the other

planets and fixed stars derive their

due light, in proportion as each has

power given to it', from 'that

light, perceptible only by the

intellect, which is the image of the

divine reason' and of God, really 'a

star above the heavens, the source

of those stars which are perceptible

by the external senses, and if any

one were to call it universal light

he would not be very wrong'.

The core text of the Hermetic

movement (second or third century

CE), also of Egyptian provenance,

states in no uncertain terms that

'the sun, through the intelligible

cosmos and the sensible as well, is

supplied by god with the influx of

good'. Setting the paradigm for

Neo-Platonic thought, another

Egyptian citizen, Plotinus (±205-270

CE), developed the idea of

hierarchic chains – or ‘emanations’

– running through the cosmos, that

convey certain qualities or energies

from higher to lower levels of

existence. The prime example was the

transmission of ‘intelligence’ from

a 'sun' in 'the divine realm' to

'soul' and on to the quotidian sun.

Dressed in Plotinus’ typical

recondite language:

'This soul gives the edge of itself

which borders on this [visible] sun

to this sun, and makes a connection

of it to the divine realm through

the medium of itself, and acts as an

interpreter of what comes from this

sun to the intelligible sun and from

the intelligible sun to this sun, in

so far as this sun does reach the

intelligible sun through soul …'

The Roman grammarian and

Neo-Platonist, Macrobius (5th

century CE), whose writings

epitomise the glorification of the

solar deity, equated this ‘cosmic

cable’ running through the sun with

'the golden chain of Homer':

'Accordingly, since Mind emanates

from the Supreme God and Soul from

Mind, and Mind, indeed, forms and

suffuses all below with life, and

since this is the one splendour

lighting up everything and visible

in all, like a countenance reflected

in many mirrors arranged in a row,

and since all follow on in

continuous succession, degenerating

step by step in their downward

course, the close observer will find

that from the Supreme God even to

the bottommost dregs of the universe

there is one tie, binding at every

link and never broken. This is the

golden chain of Homer which, he

tells us, God ordered to hang down

from the sky to the earth'.

This line of thought received its

fullest elaboration in the work of

Proclus Diadochus (412-485 CE), a

vegetarian and lifelong bachelor

heading the prestigious Academy that

Plato had founded in Athens.

Proclus’ cosmology boiled down to

the idea that space is effectively

light, as light pervades the entire

cosmos. This underlying ‘power grid’

communicates itself to the smallest

scales via channels Proclus called

seirai or ‘cords’.

Chief among these was the ‘solar

series’, which commences with the

One Being or Kronos, which is the

purest and invisible form of light,

continues through the Demiurge of

the world or Zeus and a

‘supracosmic’ sun personified by

Apollo, and ends with the ordinary

sun, Helios, which is visible to us

in the sensory world. The Demiurge

'is the "king of the universe,"

bathed in and transmitting the light

from the One, and kindling the sun

with it; hence his title "source of

the sun"'. Thus, in his Hymn to

Helios, Proclus invoked the sun as a

'dispenser of light', who does

'channel off from above a rich

stream of harmony into the material

worlds'.

An invisible substance akin to light

but more ‘ethereal’ that permeates

the entire universe and kindles the

sun and other stars – such an idea

is obviously far out from the

viewpoint of current astrophysics; a

researcher who would only cast doubt

on the accuracy of the nuclear

fusion theory of stellar powering

already runs the risk of being

fired. Yet to plasma cosmologists,

the arcane Neo-Platonic musings

about ‘cosmic cords’ or ‘strings’

transmitting the sun’s essence sound

far less abstruse. The Norwegian

scientist and explorer, Kristian

Birkeland (1867-1917 CE), was among

the first to suspect that space is

saturated with electrical currents:

'It seems to be a natural

consequence of our points of view to

assume that the whole of space is

filled with electrons and flying

electric ions of all kinds'.

Electrons, of course, move in

currents. The Swedish plasma

physicist, Hannes Alfvén

(1908-1995), further cemented the

view that space is not a vacuum,

punctuated by galaxies, but is

'filled with a network of currents

which transfer energy and momentum

over large or very large distances.

The currents often pinch to

filamentary or surface currents'.

Since then, writes another plasma

physicist, Eric Lerner, 'the idea

that space is alive with networks of

electrical currents and magnetic

fields filled with plasma filaments

was confirmed by observation and

gradually accepted … The universe,

thus, forms a gigantic power grid,

with huge electrical currents

flowing along filamentary "wires"

stretching across the cosmos'.

Could our own sun mark a ‘node’ on

one of these immense, interstellar

plasma cables known as ‘Birkeland

currents’, glowing like one unit in

a string light on a Christmas tree?

Exactly that was the thought of no

less a person than the English

astronomer, Sir John Herschel

(1792-1871), expressed in a letter

composed in 1852. Writing to his

compatriot, Michael Faraday

(1791-1867), who had posited the

existence of plasma in 1816,

Herschel wondered if the sun could

not owe its brightness to 'Cosmical

electric currents traversing space':

'If all this be not premature we

stand on the verge of a vast

cosmical discovery such as nothing

hitherto imagined can compare with.

Confer what I have said about the

exciting cause of the Solar light –

referring it to Cosmical electric

currents traversing space and

finding in the upper regions of the

Suns atmosphere matter in a fit

state of tenuity to be

auroralized by them …'

Although plasma cosmologists have

not yet followed up on Herschel’s

hunch, the Graeco-Roman thought

experiments regarding the sun’s

intermediate position on a cosmic

power cable no longer sound

outrageous on a paradigm that

already envisions a universe alive

with untold plasma wires stretching

across vast distances. Lacking the

requisite equipment used today – as

if they themselves somehow received

direct illumination from the

interstellar circuit – these

classical savants hit upon concepts

eerily similar to the ones

formulated in modern plasma

cosmology on an independent and

empirical basis. Should Herschel’s

suspicion be confirmed one day,

these prescient minds therefore rate

a mention in the roll call of

pioneers.

Contributed by Rens Van Der Sluijs

http://mythopedia.info

Books by Rens Van Der Sluijs:

The Mythology of the World Axis

The World Axis as an Atmospheric

Phenomenon

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

YouTube video, first glimpses of Episode Two in the "Symbols of an Alien Sky"

series.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three ebooks in the Universe Electric series are

now available. Consistently

praised for easily understandable text and exquisite graphics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|