|

|

|

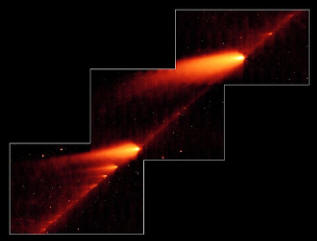

Left: This infrared image from

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope shows

the broken Comet 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann

3 skimming along a trail of debris

left during its multiple trips

around the sun. The flame-like

objects are the comet’s fragments

and their tails, while the dusty

comet trail is the line bridging the

fragments. © NASA/JPL-Caltech/W.

Reach (SSC/Caltech), 2006 May 10.

Right: Marble bust representing

Democritus of Abdera (±460-±370

BCE), who argued that comets are

composite bodies. Venice, 1700-1750

CE. Courtesy of the Victoria &

Albert Museum, London, United

Kingdom.

De-Tailing Comets

Dec 06, 2010

Science does not always

progress. A major setback in the

astronomy of the Graeco-Roman world

was the widespread adoption of the

Aristotelian worldview.

One of many fields affected by

the rise of Aristotle’s star was the

theory of comets. With much verve,

Aristotle advanced his specious

argument that comets do not exist in

space, in the arena dominated by

planets and stars, but are

restricted to the atmosphere – or

what the philosopher would call the

element of ‘air’.

Lacking any solid substance, comets

were simple ‘fires’ occupying the

same phenomenological slot as what

are known today as meteors, aurorae

and even the Milky Way, when the

comet stands on its own, or as

haloes, when it forms as a

‘reflection’ of the antics of a star

or a planet. In asserting this

palpably false opinion, Aristotle

marked a signal departure from a

bevy of pre-Socratic thinkers who

had lumped comets and planets

together.

Yet curiously, from a modern

perspective these early

theoreticians appear to have had a

better grasp on comets than

Aristotle, who actually understood

heads nor tails of the phenomenon.

According to Aristotle, 'some of the

so-called Pythagoreans say that a

comet is one of the planets, but

that it appears only at long

intervals and does not rise far

above the horizon'. Hippocrates of

Chios (±470-±410 BCE), whose ideas

displayed strong Pythagorean

streaks, and his disciple Aeschylus

'maintain that the tail does not

belong to the comet itself, but that

it acquires it …' The pair also

reasoned that the comet 'appears at

longer intervals than any of the

other stars because it is the

slowest of all in falling behind the

sun …'

Another contemporary, Diogenes of

Apollonia, classified comets as

‘stars’, a term that generally

included the planets. Apollonius of

Myndus (Fourth century BCE) is on

record with his belief that 'many

comets are planets … a celestial

body on its own, like the Sun and

the Moon'.

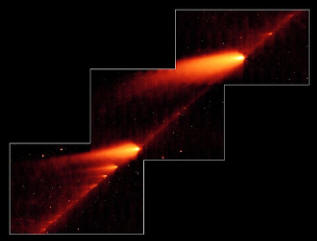

The conviction that comets are

physical bodies in their own right

facilitated the early theory,

vigorously brushed aside by

Aristotle, that they result from a

conjunction of planets. Democritus

of Abdera (±460-±370 BCE), for

example, opined that comets are a

'coalescence of two or more stars so

that their rays unite.' Thinking

along similar lines, Anaxagoras of

Clazomenae (±500-428 BCE), too, held

that 'two or more stars being in

conjunction by their united light

make a comet', 'when they appear to

touch each other because of their

nearness'.

Leucippus of Miletus (±480-±420 BCE)

was cited to a similar effect:

'Comets are due to the near approach

to each other of two planets'. Much

later still, the spiritual father of

Stoicism, Zeno of Citium (Third

century BCE), judged 'that stars

come together and combine their

rays, and from this union of light

there comes into existence the image

of a rather long star'.

To a modern cometologist,

proto-scientific speculations of

this sort seem far more up to speed

than Aristotle’s vapid postulate

that all comets are disturbances in

what we would call the earth’s

atmosphere. In grouping comets with

planets, the pre-Socratics listed

above anticipated the modern

understanding of comets as bodies in

the Solar System, whose paths may

intersect with those of planets.

Their suspicion that comets are

planets orbiting at extremely long

intervals is vindicated by current

knowledge of the periodicity of many

comets – including, of course, Comet

Halley’s well-known cycle.

More recent discoveries have tended

to corroborate even more of the

‘hunches’ Aristotle so vociferously

opposed. Observations of the rocky

cores of some comets, such as Tempel

1 in July 2005, suggest a common

ancestry not only with asteroids,

but with the rocky planets occupying

the inner region of the Solar System

themselves – a far cry from

Aristotle’s doctrine that only the

element of fire can exist in the

superlunary realm.

Conversely, detection of the plasma

tails of Venus, Mercury and the

earth, and the sodium tails of

Mercury and the moon has elicited

frequent comparisons to the tails of

comets in cutting-edge scientific

reports. Even solar prominences, now

documented in extensive detail,

might suggest a comet-like appendage

to the intellectually adventurous.

Aristotle’s opinion, which was to

dominate scholarly consensus in the

western world until the Seventeeth

century, was informed more by the

preconceived axiom that everything

in the planetary and starry heavens

is perfect and immutable than by

actual, unbiased observation. Bodies

moving on seemingly erratic paths

and exhibiting unpredictable

behaviour would upset the

mathematical elegance Aristotle and

his Platonic and Pythagorean

colleagues detected in their growing

models of planetary orbits.

Aristotle’s banishment of comets

from the serene stage of perpetually

unerring motion was really a

striking demonstration of a

so-called topdown theory – quite

unlike the bottom-up methodology

that has been cultivated since the

onset of the intellectual revolution

in Renaissance Europe. To be sure,

Aristotle did cite observational

evidence in his treatment of the

subject; however, his predilection

for ‘pure reason’ shows when he

changes tack to confront competing

views with the claim that 'the

theory can be shown to be wrong on

purely logical grounds'.

The careful reader of his

Meteorology also perceives a

certain laziness in the pundit’s

efforts to explore the pre-Socratic

theories of comets to their fullest

extent. Aristotle’s refutation of

the view that comets are akin to

planets may look superficially

plausible, but really rests on a

tacit but erroneous assumption that

comets, like planets, ought to move

on the ecliptic plane. In reality,

they are free to roam the precincts

of the planets under any angle they

see fit.

If Aristotle’s cardinal error was to

accord greater status to supposedly

undefiled reason than to the tested

method of construing theories by

deduction from sets of observation,

the reverse appears to be equally

true for his maligned predecessors.

The puzzling idea that comets are

the product of ‘planets’ in

conjunction derived at least in part

from direct observation; Democritus,

for one, 'has defended his view

vigorously, maintaining that stars

have been seen to appear at the

dissolution of some comets'.

In support of that, the Greek

historian, Ephorus of Cyme (Fourth

century BCE), claimed that a comet

once observed by all mankind ‘split

up into two stars, a fact which no

one except him reports’. The

reference was evidently to the

splitting of cometary nuclei, as

frequently recorded in modern times.

Meanwhile, Hippocrates’

perspicacious argument that the tail

is an accessory to the comet could

easily have suggested itself if

so-called ‘tail disconnection

events’ had been observed in

Antiquity.

Current knowledge of the

pre-Socratic contemplation of comets

amounts to little more than the few

surviving snippets cited above. The

loss of an entire body of literature

precludes the possibility to

determine exactly which observations

led to the remarkably precocious

hypotheses that preceded Aristotle.

The Pythagorean penchant for

information of Babylonian extraction

agrees with Apollonius’ intimation

that the scholars who analysed

comets as astral objects were ‘Chaldaeans’.

While Assyriologists have been able

to furnish only meagre support for

that statement, it is certainly

conceivable that Babylonian

astrologers passed on a body of

traditions, perhaps never committed

to writing, that would have firmly

pointed towards a deep affinity

between comets and planets.

A larger incidence of comets in the

early Holocene, for which some have

argued, would naturally have aroused

more interest in cometary diversity

and nature. As discussed elsewhere,

memories of a prehistoric time when

Venus’ plasma tail appeared within

the visible spectrum seem to have

persisted in a variety of cultures,

including late 3rd-millennium BCE

Mesopotamia.

It has also been argued that planets

in conjunction may have produced

fireworks if, at times of electrical

instability, their pointed tails

lined up, brushing against each

other. In Seneca’s words, it is then

that 'the space between the two

planets lights up and is set aflame

by both planets and produces a train

of fire'.

One of the last echoes of the

pre-Socratic idea that comets ensue

when planets approach each other may

have been Plato’s pithy reference to

the mythical Phaethon as a past

agent of catastrophe towards the end

of a ‘Great Year’. Did Plato think

of Phaethon as an earth-bound comet

spawned as all known planets

arranged in a linear conjunction?

Whatever the answer may be, Plato

and his precursors unquestionably

count as greater trailblazers in

cometology than Plato’s pupil

Aristotle, who threw caution into

the wind along with the comets.

Rens Van Der Sluijs

http://mythopedia.info

Books by Rens Van Der Sluijs:

The Mythology of the World Axis

The World Axis as an Atmospheric Phenomenon

Multimedia

“The

Thunderbolt that Raised Olympus

Mons”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

YouTube video, first glimpses of Episode Two in the "Symbols of an Alien Sky"

series.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three ebooks in the Universe Electric series are

now available. Consistently

praised for easily understandable text and exquisite graphics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|