|

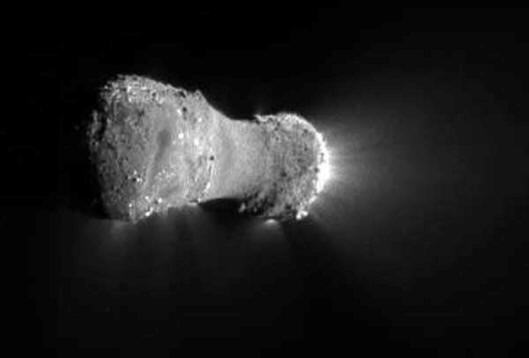

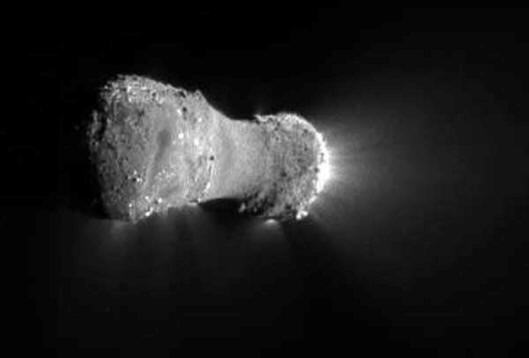

Medium resolution image of Comet

103P/Hartley 2. Credit: NASA/JPL

Hartley 2 Flyby

Nov 05, 2010

This "hyperactive" comet is

only 1.2 kilometers long but

demonstrates a nucleus more active

than comets twice its size.

As of this publication, the

EPOXI Mission spacecraft

has completed its close flyby (about

690 kilometers away) of comet

Hartley 2. The mission was not as

informative as it might have been,

since optical cameras and an

infrared imager were the only

instruments onboard the retargeted

Tempel 1 mothership.

However, as the spectacular image at

the top of the page attests, visual

results again provided confirmation

that comets are electrical in

nature.

Consensus science sees comets as

"leftovers" from the birth of our

Solar System. It is said that after

the nebular cloud from whence all

was born finished condensing into

our primary, and subsequently, all

the planets, a mass of dust and gas

formed a hypothetical spherical

shell about 30 trillion kilometers

from the Sun. The shell of frozen

material, thought to be close to

absolute zero,

is known as the Oort cloud, after

Dutch astronomer Jan H. Oort.

It is ironic that Oort inferred

the existence of the cloud that

bears his name because he only

studied 19 long period comets. Since

long period comets seem to arrive

from deep space and exhibit

extremely elongated elliptical

orbits, he could not imagine any

other solution than a cold

repository of objects beyond

astronomical observation. Note that

short period comets are known to

revolve in orbits that do not exceed

the distance to Jupiter.

More than six trillion

cometary bodies are supposed to

inhabit the Oort cloud. They are

barely held in place by the Sun's

gravity, so if stars or giant masses

of dust and gas pass too close,

tidal forces can change their orbits

and they will plunge into the inner

Solar System. Conversely, they might

be drawn out into interstellar

space.

However, what has the latest

face-to-face with a comet brought to

the table? Has there been

confirmation of the "dirty snowball"

theory? Or, as EPOXI mission

principal investigator Michael

A'Hearn summarized, is this another

in a series of surprising

experiences?

As previous Picture of the Day

articles have shown, not one image

of a comet has revealed frozen

plains, ice cliffs, slush, or snowy

crystals. Instead, Wild 2, Tempel 1,

Borrelly, Halley, and now Hartley 2

look like asteroids, with hard, dry,

rocky exteriors. Like Borrelly,

Hartley 2 is an elongated potato

tumbling through space. If asked,

this writer would say that it

resembles

asteroid 433 Eros.

What of the jets blasting into

space from isolated regions on the

comet's surface? One unidentified

participant in the live streaming

video of EPOXI's close approach

remarked, "This is almost like

Enceladus." There is no way to know

what level of insight he possesses

regarding electrical activity in

space, but his comments were

perspicacious.

The jets of vapor escaping

Enceladus at supersonic speed and

the bright jets seen on Hartley 2

(as well as other comets) pose the

same problems for space scientists:

despite their contention that narrow

vents or fissures are allowing vapor

to escape into space, no such vents

have been found. There are so-called

"tiger

stripes" on Enceladus, but

rather than being geyser-like

fumaroles, they are actually created

as electric arcs move across the

surface. The jets on comets are most

likely behaving in the same fashion.

When the Stardust mission made

its close approach to comet Wild 2,

similar jets were found. The jets of

vapor did not disperse as one would

expect gas to do in space. As was

reported in a Picture of the Day at

the time, "Chunks of the comet, some

as big as bullets, blasted the

spacecraft as it crossed three jets.

Wild 2's surface was covered with

'spires, pits and craters' that

could only be supported by rock, not

by sublimating ice or snow."

In an Electric Universe, electric

comets are most likely rocks moving

rapidly through the Sun's force

fields. They develop plasma sheaths

that can evolve into comas,

sometimes millions of kilometers in

diameter. Electric arcs connect

their surfaces with the Sun's

electric field and generate

extremely high temperatures in

isolated spots. X-rays and extreme

ultraviolet light have been detected

radiating from

comet Hyakutake, for

example.

Comets pass through a

differential electric potential as

they accelerate toward the Sun. The

variable electric field can cause

visible, glow discharges. Rather

than "dirty snowballs" or even

"snowy dirtballs," comets are

electrically active, solid bodies.

As Electric Universe advocate

Wal Thornhill wrote:

"A history of unexpected

discoveries is the hallmark of a

failed hypothesis. The electrical

model of comets was able to predict

or simply explain all of the

discoveries made during the Deep

Impact mission. The 'outbursts' from

the comet are in the form of

‘cathode jets,’ which are bursty in

nature and tend to jump around from

one high point or sharp edge to

another...Comets have not undergone

'an evolutionary process'. They are

the debris resulting from electrical

discharge sculpting of planetary

surfaces. They belong to ‘families’,

which characterize their parent

planet."

Stephen Smith

Multimedia

“When Meteorites Fell from Mars”

|