|

|

|

(Left) View of Lake Eyre from the

South (18 January 2007). © Matt

Malone

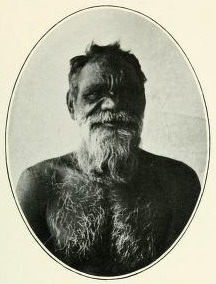

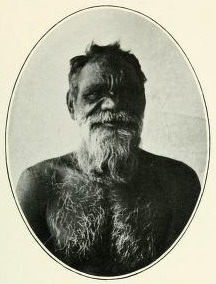

(Right) Emil Kintalakadi, a member

of the Tirari nation, east of Lake

Eyre, ±1901.

Bad to the Bones

Aug

30, 2010

Fossils

did not go unnoticed in human

societies that Victorian scholars

once disdainfully labelled ‘brutes’,

‘savages’ and ‘primitives’.

With renewed vigour, today’s

geomythologists explore the ideas

traditional cultures harboured

regarding the nature and the origin

of bones and stones they encountered

on the surface, embedded in rock, or

anywhere else.

The American classicist, Adrienne

Mayor, has documented that the first

nations of the Americas, just like

the Greeks and Romans, recognised

that fossils were the remnants of

creatures that lived in previous

eras and, in many cases, did not die

a natural death.

Intriguingly, pre-modern fossil lore

does not stop there, but often

identifies the extinct life forms

with a mythical race of beings that

dwelled in the sky before its

extermination during a cataclysmic,

lightning-charged battle, or a

world-engulfing fire or deluge.

Though compelling parallels have

been adduced, scholars have not yet

documented the global extent of such

ideas.

One case that has so far eluded

discussion in this context is the

local mythology surrounding the

bones found in the vicinity of Lake

Eyre, in the Tirari Desert of

northern South Australia. The

species represented here are

predominantly those of vertebrate

animals associated with the Tertiary

age.

The Dieri and the Tirari people, who

have traditionally lived on these

grounds, identified these bones as

the relics of a breed of “strange

monsters” known as the Kadimakara

or Kadimerkera. According to

them, these beings once dwelled in a

region in the lower atmosphere that

they described in paradise-like

terms:

'Instead of the present brazen sky,

the heavens were covered by a vault

of clouds, so dense that it appeared

solid; where today the only

vegetation is a thin scrub, there

were once giant gum-trees, which

formed pillars to support the sky;

the air, now laden with blinding,

salt-coated dust, was washed by

soft, cooling rains, and the present

deserts around Lake Eyre were one

continuous garden. The rich soil of

the country, watered by abundant

rain, supported a luxuriant

vegetation, which spread from the

lake-shores and the riverbanks far

out across the plains. The trunks of

lofty gum-trees rose through the

dense undergrowth, and upheld a

canopy of vegetation, that protected

the country beneath from the direct

rays of the sun. In this roof of

vegetation dwelt the strange

monsters known as the "Kadimakara"

or "Kadimerkera"'.

In these words, the comparative

mythologist immediately recognises a

variation on the global motif of a

past golden age, during which a

blessed stock of ancestors lived in

a ‘land’ supported by celestial

pillars. Easy traffic between the

regions above and below is a

signature aspect of the theme: 'Now

and again the scent of the succulent

herbage rose to the roof-land, and

tempted its inhabitants to climb

down the gum-trees to the pastures

below'. However, the denizens of

that hallowed land turned evil and

belligerent, according to a typical

story-line, and inevitably,

catastrophe followed. The Kadimakara

reputedly met their demise some time

after the stanchions of heaven had

subsided:

'Once, while many Kadimakara were

revelling in the rich foods of the

lower world, their retreat was cut

off by the destruction of the three

gum-trees, which were the pillars of

the sky. They were thus obliged to

roam on earth, and wallow in the

marshes of Lake Eyre, till they

died, and to this day their bones

lie where they fell'.

The story concludes with the

collapse of the solid sky, an event

that must also have been thought to

have precipitated the onset of the

dry conditions prevailing in the

area today. At least until the end

of the nineteenth century, the Dieri

continued to make pilgrimages to the

bones and hold corroborees to

'appease the spirits of the dead

Kadimakara, and persuade them to

intercede with those who still dwell

in the sky, and control the clouds

and rain'.

The British geologist and explorer,

John Walter Gregory (1864-1932), who

recorded this tradition during an

expedition in 1901 or 1902, posed

the dilemma presented by this

account:

'It may have arisen as a pure

fiction, invented by some

imaginative, storytelling native, to

explain why large bones are

scattered over the bed of Cooper’s

Creek. It may, on the other hand, be

a shadowy reminiscence of the

geographical conditions which

existed in some distant ancestral

home of the aborigines, or of those

which prevailed in Central

Australia, at some remote period'.

A little more reflection

disqualifies the former option, as

the Dieri would hardly have founded

elaborate rituals and a collective

belief on the fantasy of an

individual. Comparison of the Dieri

story with a similar tradition from

the Arrernte people, farther to the

north, suggested to Gregory that the

myth was based on a core narrative

involving the 'idea of a

sky-country, to which communication

was formerly possible by climbing up

a tree or pole'. This elementary

backbone of the story aligns itself

with the mythology of a sky-reaching

column mythologists refer to as the

axis mundi or ‘world axis’.

Gregory further concluded that the

Dieri 'have modified the story to

explain the occurrence of the great

bones in the rivers of their

country'. He made no bones of his

finding that a systematic pattern

pervades fossil lore: 'As a general

rule, where stories of giants and

dragons are assigned to precise

localities, they are founded on the

occurrence of fossil bones'.

This rule of thumb finds a much

wider, cross-cultural application.

As the outlines of the story seem to

represent a global archetype, it

stands to reason that events in the

cosmic environment surrounding the

earth spawned the myths. The

million-dollar question is whether

the tendency to link local fossils

with this mythical prototype was an

imaginary or whimsical appendix to

the myth or whether the actual

deposition of the fossils was

entwined with environmental

disasters accurately recalled by

these people.

The answer may very well prove to be

the former. However, it may not be

coincidental that Pleistocenic

vertebrates – such as the so-called

‘megafauna’ – are often among the

fossils that attract myths of cosmic

disaster. Besides some mundane

animals such as dingoes, bats,

crocodiles, rodents, and birds, the

specimens collected by Gregory’s

team also included a Diprotodon sp.

or giant wombat, which Emil

Kintalakadi, one of the last

surviving Tirari tribesmen, readily

identified as a Kadimakara.

Surveying the tribal lore, Gregory

noted that the creatures identified

as Kadimakara appear to involve 'two

distinct animals', one a water

monster possibly related to the

fossil remains of crocodiles in the

rivers of Lake Eyre, the other a

unicorn-type beast, 'a big, heavy

land animal, with a single horn on

its forehead'. A striking parallel

emerges with several North American

cultures, who likewise associated

local fossils with two groups of

mythical entities, water monsters

and their supposed rivals, the

thunderbirds.

Gregory advanced the perfectly

reasonable proposition that Dieri

people may have recognised the

perished breed of celestial monsters

in Diprotodon fossils they

sighted in their lands. Does this

preclude any direct relationship

between the fossils and the myth of

legendary sky travellers? Perhaps

not, though one must tread very

carefully.

Interdisciplinary studies involving

plasma physics and archaeoastronomy

suggest that much in the global

myths concerning the end of a

‘golden age’ can be explained on the

hypothesis of a solar storm of

unprecedented proportions, provoking

intense geomagnetic disturbances and

near-lethal synchrotron radiation

emitted by magnetospheric plasma,

possibly in combination with a

cometary interloper. These events

are conjectured to have occurred

between the end of the Pleistocene –

when a comet is also thought to have

impacted or exploded over North

America, according to Firestone and

West – and the end of the Neolithic

period.

If myths like the Kadimakara

tradition preserved a memory of this

tumultuous period, the presence of

megafauna among the purported fossil

remnants at Lake Eyre as well as in

North America, where mammoths and

mastodons exemplify the case, makes

sense.

Could it be that the Dieri, like

other pre-modern societies, had a

sense of the type of mammals that

perished during what was arguably

the latest great extinction event in

geological history? Indeed, is it

conceivable that the Dieri did not

take this myth with them from an

ancestral homeland, as Gregory

tentatively suggested, but were

already stationed on the Australian

continent at the time of these

events, witnessing the eradication

and fossilisation of the unfortunate

animals – including, possibly,

humans – first hand?

Although rock-solid evidence for

this suggestion cannot be marshalled

at this time, no stone should be

left unturned in the giant jigsaw

puzzle that is the planet’s ‘recent’

past.

Contributed by Rens Van Der Sluijs

http://mythopedia.info

Books by Rens Van Der Sluijs:

The Mythology of the World Axis

The World Axis as an Atmospheric

Phenomenon

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

YouTube video, first glimpses of Episode Two in the "Symbols of an Alien Sky"

series.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three ebooks in the Universe Electric series are

now available. Consistently

praised for easily understandable text and exquisite graphics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|