Helios Awakens

Jun 14, 2010

The

Sun is beginning to rouse itself

from a long period of quiescence.

What a difference a year can make,

not only in our personal lives, but

also in the life of the Sun. It was

in June of 2009 that heliophysicists

were reporting a period of low

sunspot activity that had not been

seen in 100 years or more. There

were almost 800 days of inactivity

between sunspot cycles 23 and 24.

However, according to a June 13,

2010 report from Spaceweather.com,

sunspot number 1081 is "crackling"

with C-class and M-class solar

flares. Solar flares are categorized

as A, B, C, M, or X: light, medium,

or powerful, with a numerical

intensity from 1 through 9 attached.

The labels are primarily used to

illustrate the potential effects

that they might have on our planet.

Thus, an X-17 flare is considered

extremely intense, while a C-4 event

will have little effect on

satellites in Earth orbit or on

electric power grids.

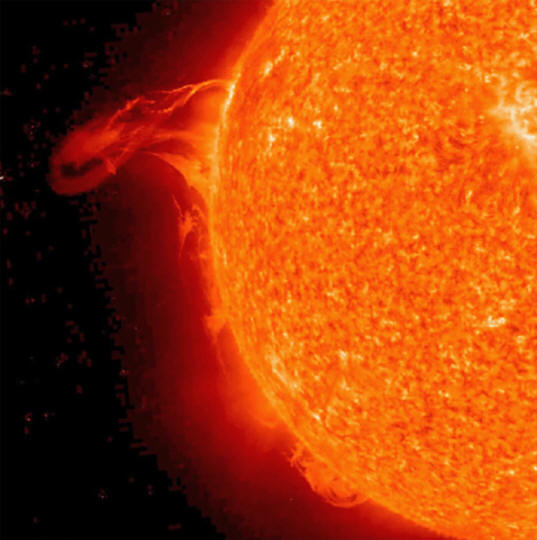

As standard theories state, solar

flares, or coronal mass ejections

(CME), occur when magnetic loops in

the Sun's atmosphere known as

"prominences" connect with each

other, causing a short circuit. The

sudden release of "magnetic energy"

is often described as millions of

hydrogen bombs simultaneously

detonating inside a confined space.

Although no one knows what so-called

"magnetic reconnection" is, it is

the only explanation offered in

science journals for why those

gigantic solar explosions appear.

CMEs eject solar plasma in the

billions of tons. A hallmark of CME

ejections is an increase in auroral

brightness and frequency, since the

flares are composed of charged

particles. Although the majority of

researchers identify the stream of

ions pouring out of the Sun as a

"wind" and that the particles "rain

down" on Earth's magnetic field, the

fact that they are attracted to and

follow the polar cusps indicates

their electrical nature.

Solar flares are sometimes

observed to leave the Sun's surface

with unbelievable acceleration. In

the past, velocities more than

70,000 kilometers per second have

been clocked. The critical factor in

that measurement is that the solar

matter continued to accelerate as it

left the Sun. If shock waves were

responsible for the initial impetus,

then surely the blast would have

begun to decelerate as it moved

toward Earth. Since the opposite

effect was seen, there must be

another phenomenon at work other

than the forces that might propel a

cannonball, for instance.

In an Electric Universe populated

by electric stars the explanation

seems obvious: electric fields in

space can accelerate charged

particles and create coherent

electric currents. According to

conventional doctrine, the Sun

accelerates electrons (and protons)

away from its surface in the same

way that sound waves are amplified.

Energetic pulsations in the solar

photosphere travel upward through

"acoustical wave-guides," called

magnetic flux tubes, that

push “hot gas” outward. Giant

formations called

spicules

rise thousands of kilometers above

the photosphere and carry the hot

gas with them.

The Electric Universe hypothesis

is based on electrodynamic

principles and not on kinetic

behavior, or even electrostatic

models. The basic premise of this

alternative view is that celestial

bodies are immersed in plasma and

are connected by circuits. Since the

Sun is also "plugged-in" to the

galaxy and to its family of planets,

it behaves like a charged object

seeking equilibrium with its

environment.

In his exhaustive work, The

Physics of the Plasma Universe

,

Dr. Anthony Peratt describes

field-aligned currents in this way:

“...electric fields aligned along

the magnetic field direction freely

accelerate particles. Electrons and

ions are accelerated in opposite

directions, giving rise to a current

along the magnetic field lines.”

Solar flares could be thought of

as tremendous lightning bursts,

discharging vast quantities of

matter at near relativistic speeds.

How those flares generate such

highly energetic emissions is a

continuing mystery to

heliophysicists.

Early in the Twentieth century,

Nobel laureate Hannes Alfvén was

contracted by the Swedish Power

Company because some of the

rectifiers used in their power

transmission circuits had exploded

for no apparent reason. When they

shorted-out more energy was released

than was contained by the plasma

flow inside them. It was

subsequently discovered that the

power from an entire 900 kilometer

long transmission line had instantly

passed through the devices. The

result was catastrophic failure and

extensive damage. Alfvén identified

the cause as unstable double layers

within the plasma flow, otherwise

known as plasma instabilities.

The circuit connecting the Sun is

of unknown length, but probably

extends for thousands of

light-years. How much electrical

energy might be contained in such

magnetically confined “transmission

lines”? No one knows, but

astronomers are continually

“surprised” by the

incredible detonations

that they observe from solar flares.

As

the electric Sun theory

relates, sunspots, flares, coronal

heating, and all other solar

activity most likely results from

fluctuations in electrical input

from our galaxy.

Birkeland current filaments

slowly rotate past the Solar System,

supplying more or less power to the

Sun as they go.

Stephen Smith