|

|

More Than Meets the Eye

Feb 10, 2010

While the

axis mundi is only a

geometric notion with no physical

substance, a smattering of

mythological and early cosmological

traditions describe it as a

conspicuous luminous column endowed

with a large number of specific

morphological features.

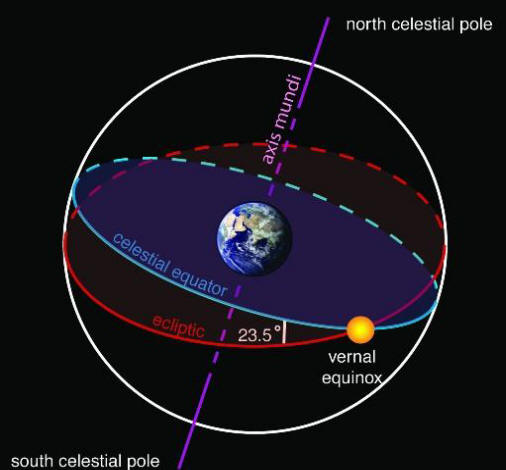

In astronomical terms, the axis

mundi or ‘world axis’ is the

imaginary line that extends outward

into space from the rotational poles

of the earth. From a viewpoint on

earth, it marks the celestial pole,

around which the stars and planets

appear to rotate in a daily cycle.

From the Roman period onwards,

natural philosophers were well aware

of the theoretical nature of the

axis’ existence. The Roman

astrologer, Marcus Manilius (1st

century CE) spoke of the tenuis

axis, the “insubstantial axis”

that “controls the universe, keeping

it pivoted at opposite poles”. He

elaborated on the “insubstantial”

nature of the axis:

“Yet the axis is not solid with the

hardness of matter, nor does it

possess massive weight such as to

bear the burden of the lofty

firmament; but since the entire

atmosphere ever revolves in a

circle, and every part of the whole

rotates to the place from which it

once began, that which is in the

middle, about which all moves, so

insubstantial that it cannot turn

round itself or even submit to

motion or spin in circular fashion,

this men have called the axis,

since, motionless itself, it yet

sees everything spinning about it.”

Much later, the African writer

Martianus Capella (5th century CE)

also commented on the ‘theoretical’

nature of the axis mundi – as

well as the poles: “I myself do not

consider an axis and poles, which

mortals have fastened in a bronze

armillary sphere to assist them in

comprehending the heavens, as an

authoritative guide to the workings

of the universe. For there is

nothing more substantial than the

earth itself, which is able to

sustain the heavens. Another reason

is that the poles that protrude from

the hollow cavity of the perforated

outer sphere, and the apertures, the

pivots, and the sockets have to be

imagined – something that you may be

assured could not happen in a

rarefied and supramundane

atmosphere. Accordingly, whenever I

shall use the terms axis, poles, or

celestial circles, for the purpose

of gaining comprehension, my

terminology is to be understood in a

theoretical sense …” Centuries

later, again, the anonymous author

of a tract attributed to the

Venerable Bede (12th century CE)

observed with respect to the earth

that “an intelligible line passes

through the middle of it from the

arctic pole to the antarctic”.

So far, so good. The intellectual

challenge arises upon the discovery

that, while the axis is only a

geometric notion with no physical

substance, a smattering of

mythological and early cosmological

traditions describe it as a

conspicuous luminous column endowed

with a large number of specific

morphological features.

At the outset, it is important to

acknowledge the distinction between

the astronomical definition of the

axis, as above, and the way the same

term is often used in

anthropological and archaeological

literature. Scholars in the

humanities typically employ the term

axis mundi in the loose sense

of a roughly vertical and stationary

connection between ‘sky’ and ‘earth’

that is mythically expressed as a

radiant tree, mountain, pillar,

ladder, rope, giant, and so on. In

this sense, which was popularised by

Mircea Eliade in particular, the

polar location of the sky pillar is

rarely specified.

The mythological and cosmological

literature worldwide is replete with

references to the axis mundi

in the loose, generic sense of the

word – in the form of stories and

statements concerning the former

existence of a stupendous visible

linkage between the realms of the

‘sky’ and the ‘earth’. Yet even much

rarer reports concerning the world

axis in the strict astronomical

sense occasionally portray the

column as a visible entity. An

example of the latter is the famous

‘pillar of Er’ described in Plato’s

dialogue The Republic. In

this, Socrates recounts the

phenomena a certain Er of Pamphylia

had observed during what would

nowadays be diagnosed as a

Near-Death Experience:

“… they came in four days to a spot

whence they discerned, extended from

above throughout the heaven and the

earth, a straight light like a

pillar, most nearly resembling the

rainbow, but brighter and purer. To

this they came after going forward a

day’s journey, and they saw there at

the middle of the light the

extremities of its fastenings

stretched from heaven; for this

light was the girdle of the heavens

like the undergirders of triremes,

holding together in like manner the

entire revolving vault. And from the

extremities was stretched the

spindle of Necessity, through which

all the orbits turned.”

This description is fairly arcane,

perhaps because Socrates needed to

speak in concealed terms to

safeguard him from hidebound

politicians. Nevertheless, its

astronomical intent is beyond

dispute and a number of ancient as

well as modern commentators were

agreed that the awesome “straight

light like a pillar” was the axis

mundi, around which the fixed

stars and planets revolved in

circles. Historians of astronomy

have argued over the question

whether Plato conceived of the axis

as an imaginary line or as a solid

object. The Neo-Platonic

philosopher, Proclus Lycaeus

(412-485 CE), who headed the

Platonic Academy in Athens for some

time, rejected the interpretation of

the ‘pillar of Er’ as the axis

mundi on the ground of the axis’

palpable invisibility: ‘For to

think, as some of our predecessors

have done, that the world axis was

meant by the light … is quite

absurd. What sort of a light is the

axis really, or how does it have a

colour more radiant than the

rainbow, as it is an incorporeal

force?’

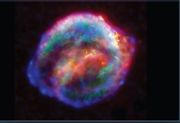

With the advent of the Space Age and

the emergence of plasma cosmology,

it is high time to revisit the issue

and enquire whether a column more

lustrous than the rainbow could have

marked the polar regions of the

atmosphere at a time in the past,

long before Manilius and Proclus

could confidently assert the

non-reality of the world axis. Could

a highly enhanced influx of

energetic particles into the earth’s

magnetosphere once have produced

aurora-like effects of such an

intensity that the Birkeland

currents joining the ionosphere to

the solar wind themselves emitted

light in the visible spectrum? After

more than a century of heated

debate, the existence of these

Birkeland currents has become

irrefragable. As these field-aligned

currents eventually reach the

auroral ovals above the earth’s

magnetic poles, the hoary notion of

one or two ‘pillars’ joining the

‘sky’ to the earth has taken on a

surprisingly down-to-earth physical

reality – except that they cannot be

seen at this time. Whereas the

rotational axis mundi remains

a purely mathematical or geometric

concept, the proximity of the

magnetic pole warrants the

association with the very tangible

reality of the earth’s highly

structured magnetosphere – a domain

populated by ions and electrons that

will give off light whenever

incoming plasmas alter its electric

and magnetic fields.

It can be established to a high

level of confidence that these

Birkeland currents, down to the

finest details, correspond to the

detailed descriptions of a sky

column in mythological and early

cosmological sources – the axis

mundi in the loose sense of the

word. For that reason,

interdisciplinarians would be well

advised to look into the question of

possible historical visibility of

magnetospheric features.

Contributed by Rens Van der Sluijs

www.mythopedia.info

Further Reading:

The Mythology of the World Axis;

Exploring the Role of Plasma in

World Mythology

www.lulu.com/content/1085275

The World Axis as an

Atmospheric Phenomenon

www.lulu.com/content/1305081

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

YouTube video, first glimpses of Episode Two in the "Symbols of an Alien Sky"

series.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three ebooks in the Universe Electric series are

now available. Consistently

praised for easily understandable text and exquisite graphics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|