home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

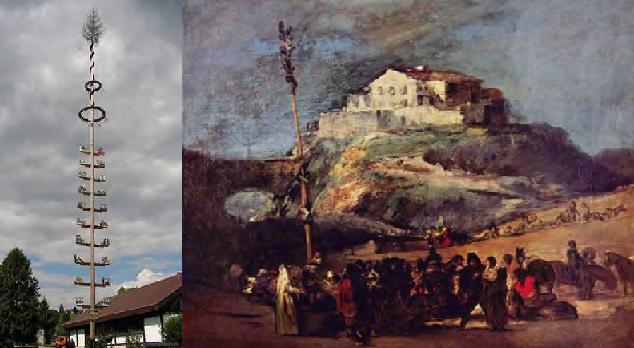

Left: Maibaum, Gestratz, Landkreis Lindau

7th August 2005 © Allgau at Wikimedia Commons.

Right: Francisco de Goya y Lucientes,

Maypole (1816-1818) Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin © The Yorck Project, 2002

May 01, 2008

Bringing in the May

The Maypole epitomizes the spirit of the religions that prevailed in northern Europe before Christianity was adopted and provides an ideal test case for the methodology employed in a comparative study of myth and ritual.The annual festival of cutting down the Maypole tree in the forest and setting it up in the town square has survived in some places and was revived in countless others, mostly in southern Germany, northeastern France, and western Czechia. But unfortunately, despite the resilience of the symbol, as little is known about the Maypole’s origins and symbolism as of the lost Germanic religions themselves.

It is imperative for all scholarly theories to distinguish rigorously between two processes of reasoning, known as induction and deduction, with corresponding “bottom-up” and “top-down” approaches to data. While the results suggested through deductive analysis often square nicely with those obtained through inductive analysis, intellectual stalemate is reached at other times. The Maypole, as well as its colleague, the Christmas tree, and countless other aspects of post-medieval folk tradition, exemplifies such an impasse.

A careful historian of religion adhering to a bottom-up approach to his research collects as much data as possible on Maypole festivities then draws his or her conclusions based on these findings alone, working backwards in time. He or she finds that the Maypole has not been attested any earlier than the late Middle Ages and vanishingly little information survives regarding the function or significance of the symbol.

Just what was the Maypole meant to signify? The inductive thinker reaches a dead end and, erring on the side of caution, is bound to describe the Maypole as a recent folklore item of uncertain origins and uncertain meaning.

Scholars allowing a top-down approach to their data, on the other hand, place the phenomenology of the Maypole in a comparative context. Close typological parallels between “modern” Maypole festivities and traditional practices known from other cultures suggest to them that, in origin, the ritual of the Maypole represents a north-European variation on the universal practice of tree and pillar cults. More specifically, recent research into the comparative mythology of the so-called axis mundi or world pillar identifies a number of striking correspondences between worldwide traits of this mythical sky-pillar and the way European people adorn and treat their Maypoles today.

A ring and fluffy “crown” seen at the apex of the Maypole compare to similar rings and feathery tops representing the “hole at the pole” at the pinnacle of the cosmic tree. Variegated ribbons suspended from the top of the Maypole are similar to the ropes and spiralling filaments attached to symbols of the sacred tree in other cultures.

The circumambulatory dance of the celebrants around the Maypole, in the course of which the ribbons are plaited together around the pillar, is just like the circular dances universally performed around cosmic trees. The ascent of the Maypole by someone who then dispenses “goodies” from the top to the crowd is reminiscent of pole-climbing rites observed in numerous cultures. And the symbolic union of the “king and queen of the May” is inseparable from the hieros gamos or “holy marriage” consummated by a divine pair at the summit of the axis elsewhere. Deductive reasoning, then, suggests that the Maypole is best analysed as an example of the axis mundi.

Which approach is right? Although the two lines of reasoning followed here seem contradictory, there is no reason for dismay. From an epistemological point of view, it is ultimately irrelevant whether a hypothetical statement is reached through inductive or deductive reasoning. What matters is that hypotheses concerning the past must be graded according to relative probability. Certainly, the possibility that Maypole rituals trace back to the same source as countless other traditions of holy trees and pillars is the most persuasive explanation for the phenomenon in town today.

The hypothesis gains even further probability in an interdisciplinary context, as the listed characteristics for the sacred pole dovetail to a fine level of detail with the modelled behaviour of a high-energy auroral pillar that people may have seen in the polar skies towards the end of the Neolithic period. From the perspective of the traditional societies of north Europe, the arrival of Spring could not have been represented better than through a replication of the towering column that reputedly embodied budding life in all its manifestations at the legendary time of creation.

Contributed by Rens Van der Sluijs

www.mythopedia.infoFurther Reading:

The Mythology of the World Axis; Exploring the Role of Plasma in World Mythology

www.lulu.com/content/1085275The World Axis as an Atmospheric Phenomenon

www.lulu.com/content/1305081___________________________________________________________________________

Please visit our Forum

The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2008: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us