home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

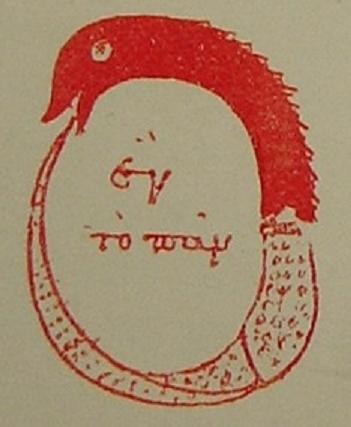

Gnostic depiction of the Ouroboros.

Codex Venetus Marcianus, 299 (2325) 11th century CE

Feb 27, 2007

Myth as MetaphorThe beginning of mythology as the study of myth traces back at least to Classical Antiquity, when Greek and Roman philosophers tried to fathom the “meaning” of their mythical heritage.

One of the most popular interpretations of myths during the Imperial Age was that they were originally construed as metaphors conveying deeper truths about the world around us. While much consensus was found in functional characterizations of the gods such as Ares-Mars for war or Artemis-Diana for the hunt, efforts were also made to uncover the symbolical meaning of more specific mythical narratives.

A popular myth, lifted from the cycle of creation mythology, was the account of the Titan Cronus-Saturn devouring his own offspring in order to retain his position as king of the gods unchallenged. His downfall transpired when he was tricked into swallowing a stone instead of the juvenile Zeus, allowing the latter to grow up and deliver Cronus his long-deserved comeuppance. The story had been known at least since Hesiod (8th or 7th century BCE) and it was not long afterwards that Cronus’ name was confused with chronos, the Greek word for “time”.

In the Orphic tradition, “Time” was personified as one of the main protagonists of creation. The folk-etymological identification of Cronus with “Chronos” then allowed for an attractive metaphorical explanation of Cronus’ cannibalism: the story symbolically signified the way time “eats” or takes away all things it has earlier produced.

This explanation was given, for example, by the Roman grammarian, Macrobius, who wrote: “It is said that Saturn used to swallow his children and vomit them forth again, a myth likewise pointing to an identification of the god with time, by which all things in turn are created, destroyed, and brought to birth again.”

Probably drawing on earlier Phoenician creation stories, the Orphics also envisioned “Time” in the form of a cosmic serpent winding itself around the universe. When the first astronomers began to model the universe as a sphere rotating on an axis, this serpent was linked with the outer circumference of the cosmos or with the ecliptic band. The ancient Near Eastern image of the ouroboros or tail-biting serpent, which had existed long before in Egypt, was then used to represent this cosmic serpent wound around the earth.

To the ancient thinkers, it was no coincidence that Saturn, the planet associated with Cronus, happened to be the outermost one of the planets, relatively close to the perimeter of the cosmos, and so the emblem of the tail-biting dragon eventually attached itself to Cronus, too. The symbolical explanation of Cronus’ infanticide and cannibalism as the destructive property of time could then be extended into an expression of the cyclicity of time: time turns back on itself and what has been before will be again.

As the full circuit of the outermost sphere of the cosmos was believed to take a year – measured with the passage of the signs of the zodiac – the year in particular was singled out as the entity personified in the figure of Cronus. And so “Saturn himself” developed into “the author of times and seasons”, according to Macrobius, while the African savant, Martianus Capella (5th century CE), described how Saturn held “In his right hand … a fire-breathing dragon devouring its own tail – a dragon which was believed to teach the number of days in the year by the spelling of its own name.”

The case of Cronus is only one example among hundreds of the metaphorical approach to myth that became so popular during the Renaissance and long afterwards. But is this popularity really justified? On closer inspection, symbolical “explanations” of the type discussed here are really the most facile mechanism one could think of when it comes to illuminating the origins of mythical motifs such as Cronus’ cannibalism or the ouroboros.

While there is, of course, some logic in the chain of ratiocination reconstructed above, the metaphorical explanation does not even begin to clarify the cosmogonic significance of the context in which the myth originated. At best it accounts for only a tiny segment of the myth, leaving unexplained why the cyclicity of time had to be represented by a snake, what Cronus’ subsequent regurgitation of his children meant, how his eventual defeat by Zeus and his exile to an island at the ends of the world are to be understood, or what the role of Zeus’ thunderbolt in the primeval battle might stand for.

Apart from that, the myths (which were thus rationalized) typically had regional variants or earlier versions that were less amenable to such rational explanations or not at all. The story of Cronus’ consumption of his children has a predecessor in a fragmentary Hurrian story, written in cuneiform script, in which Cronus’ counterpart hardly qualifies as an example of “cyclical time”. The ouroboros is a worldwide motif in mythology and ancient cosmologies, that in some societies developed into a symbol of time, as in the classical world, but elsewhere served as a form of the “circular ocean” or bore no particular significance at all.

The bottom line is that abstract, metaphorical meanings found in ancient myths are likely to be secondary developments, as the myth itself was never formed for the purpose of conveying those particular meanings. If cosmological myths and myths of creation originally commemorated changes in the electromagnetic environment of the earth, as contended on this forum, it stands to reason that the symbolism of these myths is of an altogether different nature.

These myths are indeed symbolic, not literal descriptions of what happened – there were no actual “feathered serpents” and “sky-scraping trees” in the air – but the symbols were based on visual similarity to the cosmic prototypes rather than functional similarity to the contemplated nature of time, eternity, and so on. As the original, catastrophist nature of these myths was consigned to oblivion, rational thinkers everywhere began to search for the missing “meaning” of the stories they were left with, assuming “lessons” and “parables” where there had not been any in the first place.

Contributed by Rens Van der Sluijs

www.mythopedia.infoFurther Reading:

The Mythology of the World Axis; Exploring the Role of Plasma in World Mythology

www.lulu.com/content/1085275The World Axis as an Atmospheric Phenomenon

www.lulu.com/content/1305081__________________________________________________________________

Please visit our new "Thunderblog" page

Through the initiative of managing editor Dave Smith, we’ve begun the launch of a new

page called Thunderblog. Timely presentations of fact and opinion, with emphasis on

new discoveries and the explanatory power of the Electric Universe."The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2007: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us