home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

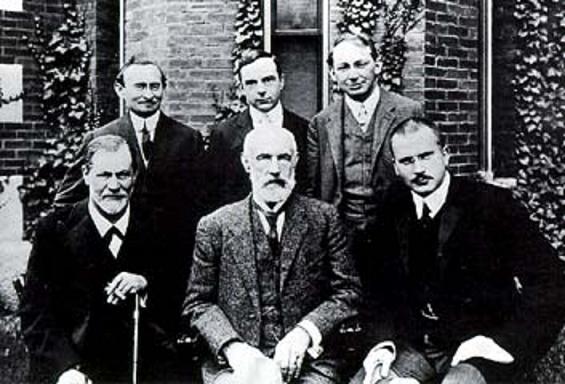

Clark University group photo September 1909.

Front row left to right: Sigmund Freud, Stanley Hall, Carl Gustav Jung.

Back row left to right: Abraham A. Brill, Ernest Jones, Sandor Ferenczi.

Credit: Sigmund Freud Museum.

Feb 11, 2008

But What About Jung?"But what about Jung?" is one of the first questions people typically ask when confronted with the possibility that ancient myths commemorate high-energy electromagnetic storms.

The elaborate psychological theories propounded by the Swiss Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) in the early 20th century have left an indelible impression on the popular understanding of myth and symbol even today. The upshot of Jung’s prolific writings on the subject is that the recurrent archetypes expressed in myths as well as dreams spring from a universal reservoir of potential forms he called the ‘collective unconscious’.

Perennial motifs such as the old hag, the soul, the trickster, the round dragon and dragon combat emerge spontaneously from this inexhaustible repository at any time and place. In other words, Jung argued that the fundamental themes of world mythology, including creation mythology, have an internal, psychological origin. How does this theory relate to the recent proposal that glowing plasmas observed from the earth formed the impetus to early myth making?

Essentially the same question can be asked for the intellectual legacy of two other giants of comparative mythology – Sigmund Freud and Joseph Campbell. The father of psychoanalysis, Freud (1856-1939) originated the concept of an individual unconscious mind, which Jung would later seize upon and extend with a ‘collective’ component. Freud famously contended that mythical motifs such as the story of Oedipus reflected repression of factors in someone’s psychosexual development.

Campbell (1904-1987), meanwhile, followed Jung’s ideas rather uncritically and, not producing any peer-reviewed work of his own, spent a lifetime expounding it, albeit in an eloquent and appealing way. Does the plasma theory of myth contradict the work of Freud, Jung and Campbell?

Before this question can be answered, it must be pointed out that Jung’s theory of archetypes and the collective unconscious, for all its erudition and elegance, is really little more than an armchair philosophy that is some way removed from the gravity and sanctity with which the cosmic themes of myth were imbued in their original settings. The theories of Freud, Jung and Jung’s unoriginal follower Campbell make a mockery of the earnest manner with which representatives of ancient societies as well as ‘traditional’ societies of more recent times handled the subject of myth.

With the most profound conviction, creation myths in their original social context were invariably reported to be true historical and earth-shaking events. The best that Jungian scholars can make of this wisdom is that these well-versed shamans, chiefs and traditional storytellers could not distinguish puerile sexual fantasies and images seen in dreams from genuine cosmic events; as if they were all wrong about their strong emphasis on the cosmic scale and setting of creation stories. Freud and Jung effectively declared the reality-claim of creation myths a delusion, if not a lie.

Although the sincerity – and also the ingenuity – of both thinkers is not in doubt, the plasma theory of myth certainly scores a point in accommodating the historicity of creation myths in the real world, pinpointing external, not internal causes to mythical content. It bears little surprise that the primary interest of both scholars – though perhaps not of Campbell – was the human mind, not mythology, as both harnessed myth to illuminate psychology, and not vice versa. This, in itself, is telling enough.

The collective unconscious theory was not just thought provoking; it was also thought-provocative. The existence of such a state or entity has never been demonstrated and it is really no more than a sophisticated disguise of a question mark. Upon checking Jung’s published evidence for the collective unconscious, it appears that the archetypal motifs did not emerge ‘spontaneously’ from the psyches of his patients. Instead, they could very easily have entered their minds through mundane education and interests.

No credible evidence warrants the existence of such a mysterious reservoir of ideas – somewhat like Plato’s hypercosmic realm of ideas – from which myths arise. On the contrary, archetypal myths are ubiquitous because their electromagnetic prototypes were observed worldwide and were commemorated in a thousand art forms.

But not all is lost. Although the Jungian paradigm of the collective unconscious does far less justice to the nature of world mythology than the plasma theory, many of the specific cases Jung – as well as Freud and Campbell – adduced to illustrate psychological resonance in myth are credible enough. The overarching theory may be wrong, but much of the evidence is still valuable and informative.

As an example, the archetypal myth of the birth of the warrior-hero describes how the youngster was at first concealed in a dark enclosure, floating on a stream of water, then emerged from this ‘egg’ or ‘basket’ amid an outpouring of light or lightning. Jungian scholars explain this birth-and-exposure myth with the psychological trauma of birth, reflecting one’s first memories as a fetus in a dark womb filled with amniotic fluids followed by the rending of the womb, the first breath and the severance of the umbilical cord.

The reconstruction of this archetypal birth myth is beyond doubt and the comparison with the ‘birth trauma’ is striking; though hard to prove, it is attractive to think that some of the myth-makers recognized this symbolism and wove it into their poetry.

But does the ‘birth trauma’ successfully account for the origins of the myths in case? To answer ‘yes’ to this question would be to deny the cosmogonic setting and the astral significance the story is given in countless ancient sources. A far more economic explanation is that the metaphors of a child, a womb, amniotic fluid, and an umbilical cord were chosen to reflect the active plasma in the sky precisely because the formations seen produced these associations in the minds of eye-witnesses on earth.

Therefore, the psychological ‘matches’ discussed in Jungian literature illuminate the psychology embedded in the choice of symbols picked to label and describe the celestial goings-on.

Contributed by Rens Van der Sluijs

www.mythopedia.info

Further reading:

The Mythology of the World Axis; Exploring the Role of Plasma in World Mythology

www.lulu.com/content/1085275

The World Axis as an Atmospheric Phenomenon

www.lulu.com/content/1305081__________________________________________________________________________

Please visit our new "Thunderblog" page

Through the initiative of managing editor Dave Smith, we’ve begun the launch of a new

page called Thunderblog. Timely presentations of fact and opinion, with emphasis on

new discoveries and the explanatory power of the Electric Universe."The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2008: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us