home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

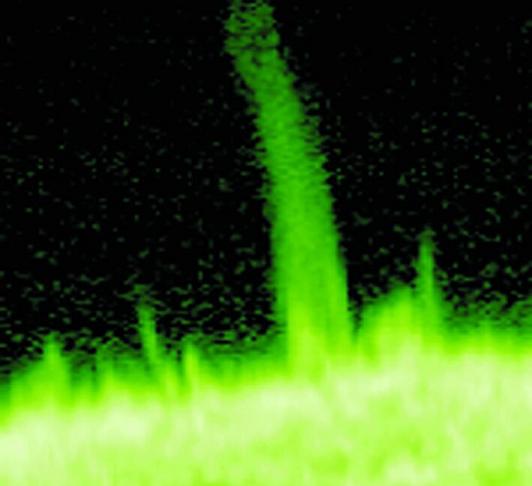

Close up ultraviolet study of the Sun.

Original image credit: SOHO/NASA/Max Planck Institute

Feb 08, 2008

Spicules Complete the CircuitColossal Birkeland currents conduct the Sun’s energy out into space but also pull electrons back into its poles.

On August 25, 1997, NASA launched the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) spacecraft carrying several high-resolution sensors and monitors designed to sample low-energy solar emissions, as well as high-energy particles arriving from intra-galactic space. From its location at LaGrange point L1 ACE has been analyzing the solar wind for the last ten years (almost a complete solar cycle), providing real-time “space weather” reports about geomagnetic storms.

Onboard the ACE satellite is the Solar Wind Electron Proton Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM) which is designed for direct scrutiny of coronal mass ejections (CME), interplanetary shockwaves and the detailed solar wind structure. Using advanced three-dimensional interpretive instrumentation, SWEPAM will coordinate its observations with the Ulysses probe, currently in polar orbit about the Sun at approximately 673,191,000 kilometers distance.One of the more unusual discoveries by the ACE/SWEPAM mission is an electron depletion in the solar wind due to “backstreaming electrons” flowing into the Sun from the surrounding space. These electrons are not in sync with the newest theories of the Sun’s activity, since the conveyance of electric charge is not considered apropos by astrophysicists. Consequently, they are left with a mystery when electrical activity presents itself in ways that they do not expect.

In the conventional view the Sun is accelerating electrons out and away from its surface through a process akin to amplified sound waves. Referred to as “p-modes”, they supposedly cause the energetic pulsations in the solar photosphere as they bounce around the Sun’s interior. When they travel upward through wave-guides called magnetic flux tubes they push the “hot gas” outward in giant structures called spicules. The spicules rise thousands of kilometers above the photosphere and carry the hot gasses (plasma) with them.

According to Bart De Pontieu and his colleagues at the Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Lab, the flux tubes are acoustic chambers focusing the “p-modes” and intensifying their sound energy. Some researchers have described this process in ways that allow them to see the Sun as a giant bell, ringing with vibratory energy. In such a theoretical model, how could sonic forces then influence a reflective process that draws negative electric charge back into the Sun? Thus the “mystery” surrounding the electron flow returning to the Sun from space.

In 1979, Ralph Juergens wrote, The Photosphere: Is it the Top or Bottom of the Phenomenon We Call the Sun? In that seminal work, he first proposed that solar spicules are actually the way that the Sun re-supplies its electrical potential and maintains its photospheric double layer. In the image at the top of the page, an unmistakable twist can be seen in the largest spicule, identifying it as a Birkeland filament. In past Thunderbolts Picture of the Day articles, we have noted that these towering filaments are responsible for the transmission of electrical energy throughout the Sun, the solar system and the galactic environment.

As Professor Don Scott, electrical engineer and author of The Electric Sky recently wrote in a private communication:

“In order to maintain the double layer above the photosphere that causes almost all the observed properties of the Sun, a certain ratio of the number of outgoing positive ions to the number of incoming electrons must exist. Quoting from Ralph Juergens: ‘In a much cited classical review paper of 1929, Irving Langmuir demonstrated that a double sheath (DL) is stable only when the current densities of the positive-ion and electron flows across [through] it are properly related. The ratio of the electron current into the tuft to the positive-ion current out of the tuft must equal the square root of the ion mass divided by the electron mass, which is to say: (electron current / ion current)^2 = ion mass / electron mass = 1836. Thus electron current / ion current = 43.’

“So there needs to be a lot more (43 times as many) electrons coming down through the DL as there are positive ions moving outward. Where do they come from?

“In that same year (1979) Earl Milton composed a paper titled, The Not So Stable Sun in which he wrote:

“‘In order to maintain a stable sheath between the photosphere and the corona a great many electrons must flow downward through the sheath for each ion which passes upward. The solar gas shows an increasing percentage of ionized-to-neutral atoms with altitude. Some of the rising neutral atoms become ionized by collision. Some fall back to the solar surface. The rising ions ascend into the corona where they become the solar wind. The descending gas flows back to the Sun between the granules - in these channels the electrical field is such that ions straying out from the sides of the photospheric tufts flow sunward, and hence the electrons flow outward. The presence of these channels is critical to the maintenance of the solar discharge…. Here we have an explanation for the spicules, huge fountains that spit electrons high into the corona.’

“In my (Don's) opinion this also explains what causes sunspots. Wherever the #p/#e ratio is not maintained, the DL collapses - the photospheric tufts disappear. So we get a spot in that location.”

By Stephen Smith

__________________________________________________________________________Please visit our new "Thunderblog" page

Through the initiative of managing editor Dave Smith, we’ve begun the launch of a new

page called Thunderblog. Timely presentations of fact and opinion, with emphasis on

new discoveries and the explanatory power of the Electric Universe."The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2008: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us