home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

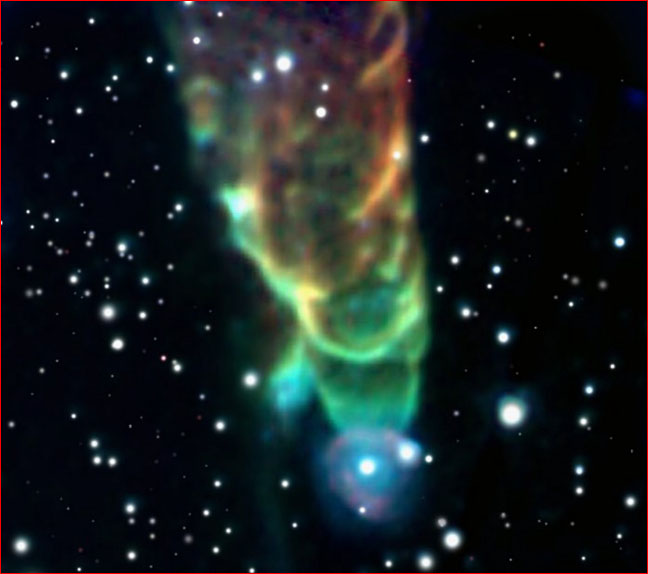

The energetic stellar jet of HH (Herbig Haro) 49/50, as seen through the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Credit: J. Bally (Univ. of Colorado) et al., JPL-Caltech, NASA.

Mar 29, 2007

A "Tornado" in SpaceWith the discovery of Herbig Haro objects, or “jetted stars”, astronomers have scrambled for explanations. But these stars, now observed by the hundreds, only accent a common and fundamental misunderstanding of space.

The image above appeared as the “Astronomy Picture of the Day” (APOD) on Feb 3, 2006. The caption identifies this stellar jet as a “cosmic tornado” light-years in length, with gases moving at 100-kilometers per second. “Though such energetic outflows are well known to be associated with the formation of young stars, the exact cause of the spiralling structures apparent in this case is still mysterious”.

In fact, astronomers express great astonishment at such formations. Gravitational models featured in twentieth century astronomy never envisioned narrow jets of anything streaming away from stellar bodies. Neither gravity nor standard gas laws would allow it.

So the problem grows worse the more we discover. To see the problem clearly, just consider the language used to describe the stellar jets of “Herbig Haro objects” such as that imaged above. The words typically employed are taken from the behavior of wind and water on a rocky planet we call “Earth”—a body that stands out as an exception in a universe that is 99.99 percent plasma and dominated by electric currents and their induced magnetic fields. A bizarre example of the outmoded language is the description of stellar jets on NASA’s Hubble Telescope website—the very page to which the APOD caption links for an explanation of “such energetic outflows”.

The explanation begins with these words: “Stellar jets are analogous to giant lawn sprinklers. Whether a sprinkler whirls, pulses or oscillates, it offers insights into how its tiny mechanism works. Likewise stellar jets, billions or trillions of miles long offer some clues to what's happening close into the star at scales of only millions of miles, which are below even Hubble's ability to resolve detail”.

Those who know what a plasma discharge is might say, “if you think a lawn sprinkler offers a good analogy for the picture above, put a sprinkler in space and try it”. Any attempt to understand stellar jets across light years of space in terms of a nozzle on one end should be a career-ending embarrassment.

To explain the narrow tornado-like jet, the Hubble page says: “Material either at or near the star is heated and blasted into space, where it travels for billions of miles before colliding with interstellar material." Does a star have the ability to create collimated jets across (not billions, but) trillions of miles by merely 'heating' material in its vicinity? The matter in the jet is hot and it is moving through a vacuum. If one is to use an analogy with water, the better example would be a super-heated steam hose. It will not form a jet of steam for more than a few feet before the steam disperses explosively.

The authors’ explanation not only contradicts simple observation and experiment, it contradicts the century-old gravitational theory on which the entire page is based. Under the popular theory of star formation, it is matter "falling" inward under the influence of gravity that creates stars. No one proposing this “nebular hypothesis” ever imagined, in advance of recent discoveries, that after gravity accomplished its mass-gathering feat, it would give way to a more powerful force evident in the jet. (As for the reference to collisions with interstellar material, that is based entirely on the bizarre explanation itself, not on anything actually observed.)

“Why are jets so narrow?” the NASA writers ask. “The Hubble pictures increase the mystery as to how jets are confined into a thin beam”. Then, after noting that the Hubble pictures tends to rule out the idea (popular just a few years ago) that a disk around the star could provide the needed “nozzle”, the authors note: “One theoretical possibility is that magnetic fields in the disk might focus the gas into narrow beams, but there is as yet no direct observational evidence that magnetic fields are important”.

Following this virtual dismissal of magnetic fields, the authors pose two questions which bear directly on the role of magnetic fields, though they are clearly unaware of the connection. “What causes a jet’s beaded structure”, they ask. And “why are jets ‘kinky’”? They do not realize that they have just cited two of the most easily recognized features of plasma discharge—“beading” and “kink instabilities”. But rather than enter the world of electrified plasma, so unfamiliar to astronomers, the web page takes us into “waterworld”. “…The beads are real clumps of gas plowing through space like a string of motor boats”. And the “kinks along their path of motion” can be seen as evidence for a stellar companion, one that “pulls on the central star, causing it to wobble, which in turn causes the jet to change directions, like shaking a garden hose”.

It is statements such as this that cause plasma experts—those who have spent a lifetime observing the unique behavior of electric currents and electric discharge in plasma—to wonder about the future of theoretical science. For the cosmic electricians there is nothing out of the ordinary in stellar jets. Their counterparts appear regularly in the plasma laboratory. They can be modeled in computer simulations. Their analogies can be seen in Earth’s upper atmosphere, in Martian dust devils, in the volcanoes of Jupiter’s moon Io, on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, in the jets and tails of comets, in the penumbra of sunspots—and even in the vast polar jets now seen exploding from distant galaxies.

If the electrical theorists are correct, those offering conventional answers to newly discovered objects in space need a crash course on plasma and electricity.

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2007: thunderbolts.info