home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

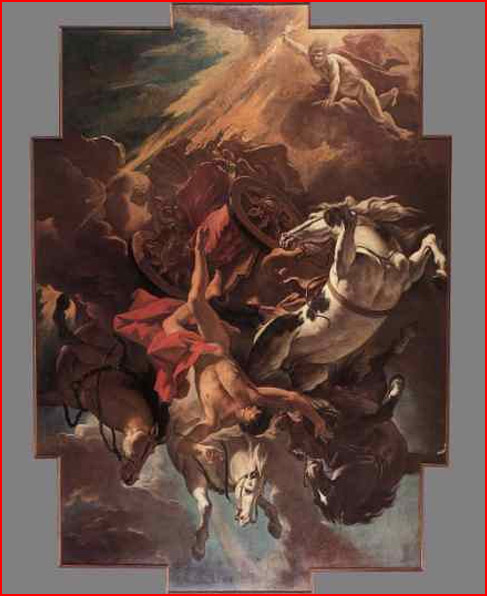

Fall of Phaeton by Sebastiano Ricci. Painted 1703-04.

From the Museo Civico, Belluno

Feb 21, 2007

The “Amber” Beads of Phaethon

Some of the more abstruse mythical traditions recorded in ancient times receive remarkable illumination in the light of modern scientific knowledge concerning certain spectacular atmospheric events.In one of the most graphic Greek myths, the “son of the sun,” called Phaethon, in a vain attempt to replace his father crashed down from the sky, set the world ablaze, and drowned as he fell into the river Eridanus. As a curious footnote to this popular tale, classical authors commonly noted that Phaethon’s lamenting sisters, the Hesperides, shed tears of amber in this river. As the mythographer, Apollonius Rhodius, explained:

“And all around the maidens, the daughters of Helios, enclosed in tall poplars, wretchedly wail a piteous plaint; and from their eyes they shed on the ground bright drops of amber. These are dried by the sun upon the sand; but whenever the waters of the dark lake flow over the strand before the blast of the wailing wind, then they roll on in a mass into Eridanus with swelling tide.”

That the ancients did not regard this aetiology of amber as incidental to the story can be seen in the fact that they apparently used the presence of amber as a weighty argument in their respective geographical identifications of the mythical river. The popular equation of the Eridanus with either the Po or a river in the far north of Europe thus corresponds with the fact that the Baltic and northern Italy were widely known in ancient days as large repositories of amber. But how does this relate to a parallel tradition, according to which Phaethon fell in Libya? As Pliny noted, “Theophrastus states that amber is dug up in Liguria, while Chares states that Phaethon died in Ethiopia on an island the Greek name of which is the Isle of Ammon, and that here is his shrine and oracle, and here the source of amber.” Again, “Theomenes tells us that close to the Greater Syrtes is the Garden of the Hesperides and a pool called Electrum, where there are poplar trees from the tops of which amber falls into the pool, and is gathered by the daughters of Hesperus.” The trouble is that the oasis alluded to here is decidedly not known as a deposit of amber, so what could these traditions be referring to?

The key might be that the Greek word routinely translated as “amber,” electron, may not always refer to the fossil glassy resin of trees known as amber. The Greeks were no chemists in the modern sense and there is a distinct possibility that electron may have denoted other minerals with a superficial resemblance to amber. Significantly, the Libyan desert has yielded glassy beads – associated with an impact in the giant Kebira crater – that are now analysed as fulgurites or silica minerals fused in the heat from a lightning strike. The possibility that the Libyan amber associated with Phaethon really was fulguritic in origin wins much likelihood in view of the widespread belief that it was Zeus’ thunderbolt that had brought the demigod down from the sky, as Ovid wrote, “to quench fire with blasting fire.” The superficial incoherence of the ingredients of the myth dissolves on the hypothesis of a catastrophic thunderbolt and it requires no big leap of the imagination that myth-makers could conceive of the transparent substance both of fulgurites and amber as the hardened tears of Phaethon’s companions.

Alternatively, the term electron may have described tectites, glassy spherules formed from the melting and rapid cooling of terrestrial rocks that were vaporised by the high-energy impacts of large meteorites, comets, or asteroids upon the earth; many scholars consider the so-called Libyan Desert glass to be a form of tectite. This, too, makes sense of the myth, as ancient and modern authorities alike have often discerned a strong meteoritic or cometary component in the motif of Phaethon’s fall. Ovid’s description again offers the classic example: “But Phaethon, fire ravaging his ruddy hair, is hurled headlong and falls with a long trail through the air, as sometimes a star from the clear heavens, although it does not fall, still seems to fall.” There is enough evidence to suggest that Ovid was neither original nor alone in this respect and general studies in the field of comparative religion have borne out that the symbolism of lightning and meteors was often fused in the ancient world-view.

The association of Phaethon’s fateful fall with the origin of electron strongly suggests that the formation of this substance as a result of a streak of intense light from the sky – whether a lightning bolt or a meteor – was observed by those that created the myth. Similar knowledge must have obtained in other cultures. The Maya, for instance, regarded the supreme creator, Heart of Sky or Huracan, “Hurricane,” as a triple deity, representative of three types of lightning. As Tedlock observed, two of these “refer not only to shafts of lightning but to fulgurites, glassy stones formed by lightning in sandy soil.”

Contributed by Rens van der Sluijs

____________________________________________________________Please visit our Forum

The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2007: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us