home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

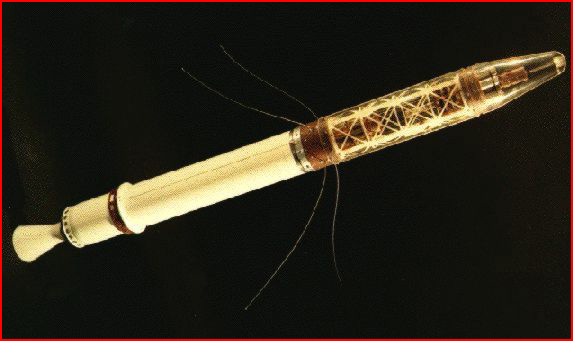

Credit: Courtesy JPL, NASA

Oct 13, 2006

Discovering the MagnetosphereThe discovery of the two Van Allen Radiation Belts could be called the first surprise of the space age. But scientists might not have been surprised had they paid attention to the experiments of plasma scientist Kristian Birkeland.

In a basement lab of the physics department at the University of Iowa, James Van Allen designed Explorer 1, a scientific satellite for the International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957-1958. The satellite carried only a single instrument, a small Geiger counter to record energetic particles. The instrument was designed to measure cosmic rays, highly energetic ions (positively charged particles) of unknown origin arriving from distant space.

Strangely, though the experiment detected many particles at low altitudes, at the top of the orbit it counted no particles at all, The explanation for this odd behavior was discovered two months later by Explorer 3. This new satellite included a tape to record data continuously. The data revealed that the "absence" of cosmic ray counts from Explorer 1 actually signified extremely high radiation. "So many energetic particles hit the counter at the higher altitudes that its mode of operation was overwhelmed and it fell silent," states a NASA account. "Not only was a radiation belt present at all times, it was remarkably intense".

Scientists had discovered what we now know as the innermost of the two Van Allen Radiation Belts, a finding hailed as the first important discovery of the space age. It could also be called the first surprise of the space age, since astronomers had not expected intense radiation around the Earth.

Had they paid more attention to Birkeland's experiments it need not have been a surprise. In fact his terrella experiments demonstrated most of the phenomena found by spacecraft near the Earth. But for scientists the stumbling block was that the terrella required electrical power input to the Earth, and standard astrophysics has no mechanism to support such a model.

In the half-century following Explorer 1, almost all the great surprises of space age exploration of the solar system have involved electromagnetic activity. We now know that the Earth is surrounded by a complex structure of magnetic fields and high-speed charged particles that include streams of electric current around the Earth. This structure has been named the "magnetosphere" under the assumption that it forms the boundary between the Earth's and the Sun's magnetic fields.

However, comets form similar protective sheaths, visible as their comas, without having magnetic fields. In a plasma discharge most objects naturally form a Langmuir plasma sheath that prevents direct contact with the enveloping plasma. Magnetospheres are merely a more complex form of Langmuir sheath, with the magnetic field of the body trapped within the sheath. If standard theory failed to anticipate these discoveries, surely the primary reason lies in the failure to recognize that planets are embedded in a solar electric discharge and consequently enveloped by Langmuir sheaths.

For these reasons, the original contributions of Kristian Birkeland should no longer be ignored.

___________________________________________________________________________Please visit our Forum

The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITORS:

Steve Smith, Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Dwardu Cardona, Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Brian Talbott

Copyright 2006: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us