home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

picture of the day archive subject index

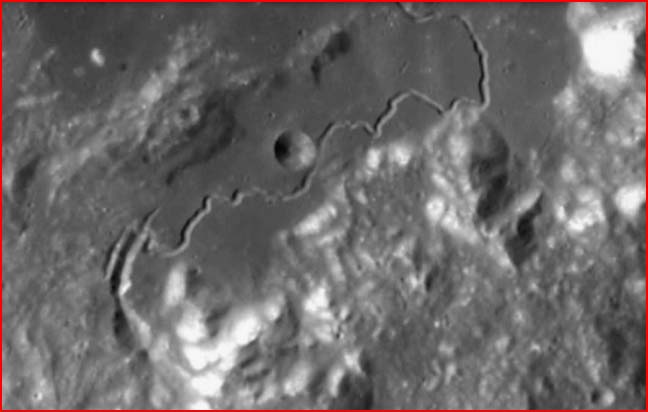

Credit: ESA/Space-X

This SMART-1 picture of Hadley Rille offers the best look yet at a deep gash cutting across Hadley (far left).

Mar 21, 2006

The Moon and Its Rilles

A Partnership of Craters and RillesIn the history of lunar exploration, the mysterious association of craters and rilles has provoked a number of mutually contradictory hypotheses, none of which is sufficient to explain things seen in high-resolution pictures of the Moon.

In our previous looks at the lunar craters Tycho and Aristarchus, we observed that the popular “explanation” (the impact hypothesis) is contradicted by features that, in close-up photographs, invariably leap out at the critical observer.

Similarly, when we consider details of the “sinuous rilles” Schroeter’s Valley and Hadley, we discover that common teachings require things that are not there while ignoring things that are there.

The message conveyed by these prominent lunar features carries broad implications for our understanding of the lunar surface at all scales of observation. Our claim has been that theoretical assumptions in planetary science—including the most popular teachings in lunar geology—cannot withstand a critical review.

Yet there is a vantage point from which the accumulated anomalies and contradictions disappear. The electric hypothesis does not arbitrarily separate issues of crater formation from issues of rille formation. In one instance after another, we see that craters and rilles stand in a partnership that is far too pervasive to be accidental. And this convergence is predictable under the electric hypothesis.

Dominating craters on the Moon are surrounded by non-radial crater chains, irregular concentrations of smaller craters, sinuous or filamentary channels, and deep gashes—the very features seen in electrical arcing experiments and in electrical discharge machining in industrial applications. To underscore these surface patterns on the Moon, we have placed two large images of the Euler Crater region here and here. (The files are large—1.5mb and 1.8mb respectively—but they are worth the look).

The pictures show innumerable small crater concentrations, crater chains, and gashes, one form merging with another in every imaginable way. A modest number of the gashes might be mistaken for impacts at oblique angles, were it not for the repeated instances in which the gashes are constituted of overlapping craters, or are too long, or change direction—attributes that exclude “explanation-by-impact”. In this sense, an unbending adherence to the impact theory can only encourage theorists to ignore these defining features on the lunar surface.

The standard picture only grows more incoherent when we consider the numerous rilles and enigmatic channels that are conventionally “explained” as lava erosion. Why do they exhibit craters and crater chains of a sort never found in association with known remains of flowing lava? Look at the higher-resolution image we presented earlier of the Aristarchus region here. In the lower left of the picture is a rille that divides into twin channels, both of which end in large craters. Could this anomalous channel have been formed by flowing liquid of any kind? It is simultaneously a crater chain and a rille, confirming the point made repeatedly by the electrical theorist Wallace Thornhill: The same force that produces crater chains produces rilles.

Rilles often exhibit craters deeper or wider than the channels on which they are centered. For a good example, consider the picture of Rima Hyginus here. In many instances the larger craters centered on a rille appear at the “joints” of a meandering channel. Could they be “collapsed lava tubes,” a once-popular hypothesis? It is only necessary to look closely to see that these formations never reveal rubble from a collapsed “roof”.

Not infrequently, we also observe a secondary stream of smaller craters meandering down the rille, as we saw along the floor of Schroeter’s Valley. The electrical theorists point to analogs in both laboratory arcs and in lightning-excavated trenches. On the moon, a fascinating example is Vallis Alpes, a spectacular channel that extends some 166 kilometers, cutting across the mountain range Montes Alpes. Clearly, it was not cut by flowing liquid! See pictures here and here. Along its mid section it is about 10 kilometers wide. Meandering down the center of the flat valley floor is a narrow rille punctuated by circular craters.

Inexplicable gashes emerging from craters or converging with crater chains are ubiquitous on the lunar surface. Our picture of Hadley Rille above, recently taken by the ESA SMART-1, shows an “inexplicable” gash on the far left. The long and deep gash emerges from the narrow end of a balloon-like crater to cut across Hadley. It certainly has no explanation in standard theory, and most lunar scientists simply address it as a “gash” and go on to something they “understand”.

To put all of this in perspective, we must remember that the craters, rilles, crater chains, and gashes on the Moon can now be systematically compared to analogs on other bodies to see whether scientists have been able to forge a coherent interpretation. We find that, as the quality of the pictures has improved, the interpretations have grown increasingly fragmented and bizarre. For a telling comparison of the lunar enigmas to those presented on another body, look at the so-called “collapse pits” on the Martian “volcano” Arsia Mons. All of the lunar enigmas are there in one place—craters, crater chains, gashes, and rilles—except that here the stunning clarity of the pictures gives common sense a distinct advantage. Are these formations the result of “surface collapse”, or has material been cleanly removed from the surface by a force unknown to planetary scientists? In a contest with the inertia of prior belief, common sense will surely win out in the end.

__________________________________________________________________________

Please visit our new "Thunderblog" page

Through the initiative of managing editor Dave Smith, we’ve begun the launch of a new

page called Thunderblog. Timely presentations of fact and opinion, with emphasis on

new discoveries and the explanatory power of the Electric Universe."The Electric Sky and The Electric Universe available now!

|

|

|

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITOR:

Michael Armstrong

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Dwardu Cardona, Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Michael Armstrong

Copyright 2006: thunderbolts.info

![]()

home •

thunderblogs •

forum •

picture of the day •

resources •

team •

updates •

contact us