home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

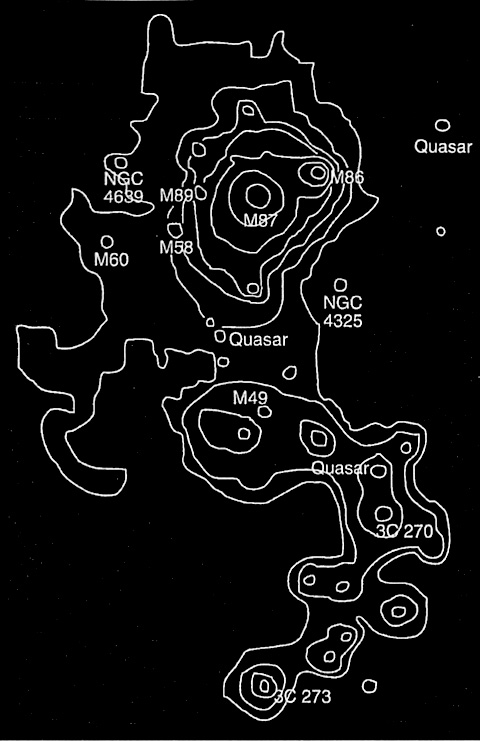

Credit: Halton Arp, Seeing Red, p. 131.

pic of the day

archive

subject index

abstract

archive

Links:

Society for

Interdisciplinary

Studies

Redshifts, Cosmology and Academic Science

Author: Halton Arp, 6"x9" paperback, 314 pages, ISBN:0-9683689-0-5

A wonderful book, Seeing Red is a must read since it is both

educational and hard-hitting while being readable and entertaining. Arp

dismantles conventional astrophysics, based on redshift being

proportional to distance, by sharing his observations on quasars,

some of which are highly redshifted yet connected to low redshifted

galaxies by material bridges. Writing eye-opening material in more

than one arena, Arp takes on the corruption of good science in

academia, government and publishing after giving us great material

concerning red shift, the Big Bang, and cosmology.

Seeing Red can be ordered

via the link below.

Order Link $25.00

Nov 01, 2005

A Bigger View of the Virgo Cluster

“[T]he professional tends to interpret the pictures

by using the theory he was taught while the amateur tries to use the

picture to arrive at a theory.”

Halton Arp, Seeing Red

When all we could see was the visual part of the electromagnetic spectrum, the universe seemed to consist of dots of fire isolated in a dark emptiness. With telescopes, we could see galaxies of dots and clusters of galaxies, but our theories about them continued to reflect our sensory bias: Tiny flames separated by long intervals could affect each other only with feeble nudges of gravity.

Then came the instruments that enabled us to “see” almost the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays. We “saw” rivers of radiation connecting the visible dots. Swirls of high-energy interactions joined together galaxies, compact clusters and quasars. The connected dots made up a bigger picture, a fuller picture, a picture that required new theories to understand it.

Illustrated above is a “contour map” of the x-ray intensity around the Virgo Cluster of galaxies. M49, an active elliptical galaxy (near the middle of the swirl), is the largest member of the cluster. (A line of quasars—not shown—extends through it in a northwest-southeast direction.) On opposite sides of it, only a few degrees away and engulfed in the stream of x-ray-emitting material, are M87 to the north (top) and 3C273 to the south (bottom). 3C273 is a quasar that has a jet pointing at an elongated hydrogen cloud to the southwest (lower right). In gamma-ray maps, a bridge of gamma-ray-emitting material connects the quasar with a variable quasar, 3C279, to the southeast and also back toward M49.

M87 is also an active galaxy with a jet extending to the northwest (upper right). Beyond the jet are the radio- and x-ray-emitting galaxies M86 and, close by, M84. Further along the line is a quasar that has a pair of quasars aligned across it. Several elliptical galaxies lie along the M87-M86 line, and an oval of higher-redshift spiral galaxies surrounds the line.

More quasars are embedded in the swirl of x-ray emission, and several of the unlabeled regions of increased intensity are compact clusters of small, visually faint galaxies.

The bigger picture that emerges from connecting the dots is that of galaxies ejecting quasars and highly excited material in opposite directions from the galaxies’ nuclei. The ejected quasars in turn eject material as they evolve into next-generation galaxies. Quasars that are fragmented evolve into compact clusters of galaxies. In this bigger picture, redshifts are indicators of age, not distance.

M49, with a low redshift, would be the “mother” of the Virgo Cluster. M87, with a slightly higher redshift, would be an early ejection. The compact cluster between M49 and M87 and the quasar 3C273 on the opposite side of M49, both with nearly the same much higher redshift, are likely an ejection pair. As M49 rotated, later ejections spewed out x-ray-emitting material that formed the spiral shape, just as a spinning garden hose throws out a spiral of water.

M87 is famous for its jet with knots of increased brightness along it: We see the galaxy in the process of ejecting material. The elliptical galaxies, x-ray galaxies, compact clusters and quasars beyond the jet are older knots in the ejection. They have already ejected material to the sides, some of which has evolved into small spiral galaxies.

Until the x-ray map connected all these disparate dots into a single organic structure, they were thought to be isolated bodies at vastly different distances from each other. The theories that dictated those separations must now be abandoned in favor of theories that can explain their connections.

[See Arp's lecture video, "Intrinsic Redshift," for more details of this new picture of the universe.] Available from Mikamar Publishing

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITOR:

Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona, Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Michael Armstrong

Copyright 2005: thunderbolts.info