home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

Credit: NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems

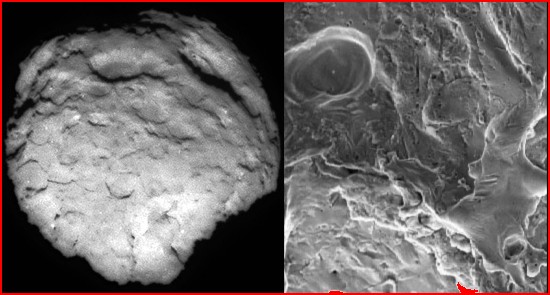

Comet Wild 2 is

shown in close-up above. Beside it is a microscopic view of an EDM

(electrical discharge machined) surface. Note the flat-floored

depressions with steep

scalloped walls and terracing. The small

white spots on the comet can then be reasonably

identified as the

active cathode arcs that produce the cometary jets.

pic of the day

archive

subject index

abstract

archive

Links:

Society for

Interdisciplinary

Studies

Sep 23, 2005

Comets: The Loose Thread

Spacecraft have now visited four comets. What they found contradicts what was expected and falsifies accepted comet theory. But that theory is woven with every other astronomical theory into a cosmology that defines the universe as we know it. The fall of comet theory will inevitably bring us a new and different universe.

Comets are giving accepted comet theory a hard time. Close-up images of comet nuclei from spacecraft have contradicted about every expectation of theory. (“Expectation” is a euphemism for “prediction”; a disappointed expectation is practically the same thing as a failed prediction, except with the former you don’t expect you’ll have to discard the theory.) “If astronomy were a science,” as one astronomer put it, theoreticians would admit that the theory had been falsified, and they would start over with an eye to the evidence. Instead, they hang on to the theory with ever more stubbornness and hope a little tinkering and adjusting will bring the facts into line.

The facts are apt to be more stubborn than the theoreticians: Deep Impact kicked up ten times more dust than expected and stimulated the comet's activity a magnitude less than expected. The dust was not a conglomeration of sizes as expected but was consistently powder-fine. The nucleus of the comet was covered with sharply delineated features, two of which were circular enough to be called impact craters. This was not expected for a dirty snowball or a snowy dirtball or even a powdery fluffball.

The craters, of course, weren’t actually called impact craters. They must have been caused by subsurface explosions, because they had flat floors and terraced walls, despite the myriad of other craters on rocky planets and moons with flat floors and terraced walls that are called impact craters. All the other circular depressions with flat floors and terraced walls weren’t craters because they had “unusual shapes”.

The hard times began with Comet Halley. Theory expected more or less uniform sublimation of the surface as the nucleus rotated in the sun, much as you would expect of a scoop of ice cream on a rotisserie. But Halley had jets. Less than 15% of the surface was sublimating, and the ejecta was shooting away in thin beams.

The theory was adjusted to introduce hot spots, chambers below the surface in which pressure could build up and erupt through small holes to produce the jets. It went unmentioned that the holes must have been finely machined, like the nozzle of a rocket engine, in order to produce the collimation of the jets: Just any rough hole would result in a wide spray of gases.

Borrelly made the hard times harder. It was dry. And black. Theoreticians tinkered with the dirty snowball theory until they got the dirt to cover the outside and to hide the snow inside. Somehow they got the dirt, which ordinarily is an insulator, to conduct heat preferentially into the rocket chambers to keep the jets going.

Wild 2 defied them. Its jets were not just around the sub-solar point, where the Sun’s heat would be greatest. This comet sported jets on the night side. The rocket chambers now had to store heat for half a “comet day”. And something was needed to keep the jets coherent over great distances and to gather their emissions into a stream of clumps: Clusters of particles repeatedly struck the spacecraft.

Comet theorists announced that comets were mysteries and that the theorists knew nothing, that they had to “think differently”. Then they proposed adjustments to the accepted theory that would be acceptable to the accepted way of thinking.

Different theories abound—but outside the walls of astronomical acceptability. For an astronomer to recognize their existence would be to jeopardize his position and salary. But the characteristics of comets that are so difficult to explain with snowballs are fairly easy to explain with electricity.

Electrical theories date back to the 1800s, before “electricity” became taboo in astronomy. They were well-founded on observations and on the proven laws of electromagnetism. In the last few decades, they have been refined to the point where they expected the findings that were so hard on the fashionable theory:

Comets are electrical discharges in the thin plasma that permeates the solar system. Because they spend most of their time far from the Sun, their rocky nuclei are in equilibrium with the voltage at that distance. But as they accelerate in toward the Sun, their voltage is increasingly out of equilibrium with the voltage and increasing density of the solar plasma. A plasma sheath forms around them—the coma and tail. And filamentary currents—jets—between the sheath and the nucleus erode, particle by powdery particle, the circular depressions with terraced walls that are typical of electrical discharge machining. As the discharge channels move across the surface of the comet, they burn it black.

If it were only a matter of explaining with plasma discharges the jets and the blackened rocky surfaces and the powder-fine dust and the terraced depressions, there might not be so much blinkered stubbornness. But modern astronomical theories have been worked into an interlocking web of explanation. Each theory supports, and is in turn supported by, nearly every other theory. If one theory frays, if one loose thread is pulled, the entire fabric will unravel.

An electrified comet requires an electrified Sun. The Sun is the focus of the electric field that causes the comet to discharge. For the Sun to maintain its electric field, it (and all stars) must be the focus of another electric discharge within an electrified galaxy. And electrified galaxies, with their magnetic fields and x-ray emissions and ejections of quasars, must be connected in larger circuits that render meaningless such fancies of cosmology as the Big Bang theory.

If you pull one electrified comet out of the well-knit structure of accepted theories, the entire garment will become unacceptable. Either the universe is an agglomeration of isolated, gravitating, non-electrical bodies, or else it is a network of bodies connected by and interacting through electrical circuits. Either the universe is a gravity universe or it is an Electric Universe.

And comets are the loose thread.

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITOR:

Mel Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona, Ev Cochrane,

C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Michael Armstrong

Copyright 2005: thunderbolts.info