home •

about •

essential guide •

picture of the day •

thunderblogs •

news •

multimedia •

predictions •

products •

get involved •

contact

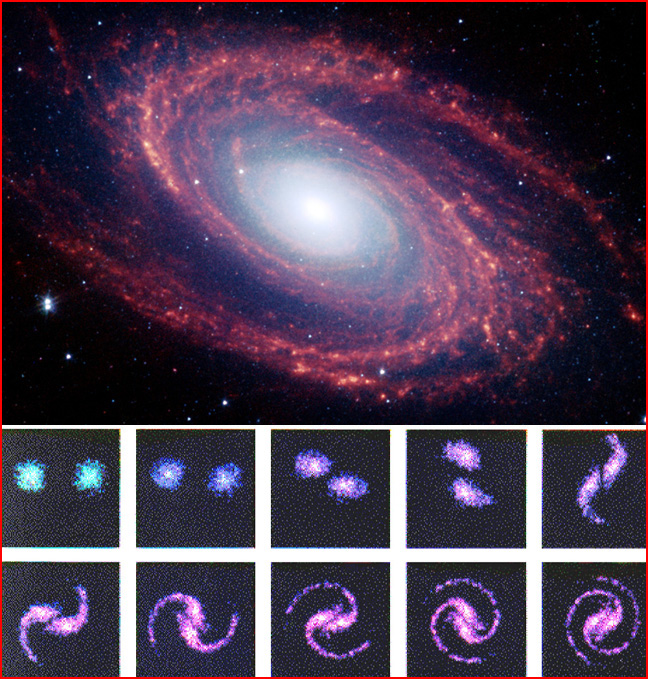

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/S. Willner (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics)

pic of the day

archive

subject index

abstract

archive

Links:

Society for

Interdisciplinary

Studies

May 02, 2005

Plasma Galaxies

Laboratory experiments, together with advanced simulation capabilities, have shown that electric forces can efficiently organize spiral galaxies, without resorting to the wild card of gravity-only cosmology--the Black Hole.

Many of astronomy's most fundamental mysteries find their resolution in plasma behavior. Why do cosmic bodies spin, asked the distinguished astronomer Fred Hoyle, in summarizing the unanswered questions. Plasma experiments show that rotation is a natural function of interacting electric currents in plasma. Currents can pinch matter together to form rotating stars and galaxies. A good example is the ubiquitous spiral galaxy, a predictable configuration of a cosmic-scale discharge. Computer models of two current filaments interacting in a plasma have, in fact, reproduced fine details of spiral galaxies, where the gravitational schools must rely on invisible matter arbitrarily placed wherever it is needed to make their models "work".

The photograph of spiral galaxy M81 above is one of the first images returned by NASA's new Spitzer space telescope, an instrument that can detect extremely faint waves of infrared radiation, or heat, through clouds of dust and plasma that have blocked the view of conventional telescopes. The result is the picture of striking clarity.

Beneath this photograph we have placed snapshots from a computer simulation by plasma scientist Anthony Peratt, illustrating the evolution of galactic structures under the influence of electric currents. Through the "pinch effect", parallel currents converge to produce spiraling structures.

To see the connection between plasma experiments and plasma formations in space, it is essential to understand the scalability of plasma phenomena. Under similar conditions, plasma discharge will produce the same formations irrespective of the size of the event. The same basic patterns will be seen at laboratory, planetary, stellar, and galactic levels. Duration is proportional to size as well. A spark that lasts for microseconds in the laboratory may continue for years at planetary or stellar scales, or for millions of years at galactic or intergalactic scales.

Plasma experiments, backed by computer simulations

of plasma discharge, are changing the picture of space. Plasma

scientists, for example, are able to replicate the evolution of galactic

structures both experimentally and in computer simulations without

recourse to a popular fiction of modern astrophysics

See also:

Jan 05, 2005

A Loose Cannon in Space

July 08, 2004

Driving Forces of the Milky Way

Apr 15, 2005

Electric Motor of the Milky Way

July 23, 2004

Galaxy Filaments

July 14, 2004

NGC 1232

Jan 13, 2005

Seeing Circuits (2)

Nov 08, 2004

The Milky Way Family

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

David Talbott, Wallace Thornhill

MANAGING EDITOR: Amy Acheson

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: Mel Acheson, Michael Armstrong, Dwardu Cardona,

Ev Cochrane, C.J. Ransom, Don Scott, Rens van der Sluijs, Ian Tresman

WEBMASTER: Michael Armstrong

Copyright 2005: thunderbolts.info