|

Ancient stories of

cosmic battles, pitting a celestial warrior against a

serpent, dragon, or other monster, were integral to the

birth of civilization. From one early culture to

another, sacred monuments and rites, religious texts,

and cosmic symbols harked back to the age of the gods,

to earthshaking upheaval, and celestial combat.

One fact is

frequently overlooked, however. The context and setting

of the later stories progressively changed as the gods

were brought down to earth. Over time, the poets and

historians placed the stories on a landscape familiar to

them. In the course of Egyptian history, for example,

the creator Ra and his regent Horus, whose original

domain was undeniably celestial, came to be remembered

as terrestrial kings. In later time, when Greek and

Roman poets, philosophers, and naturalists sought to

gather knowledge from far flung cultures, Egyptian

priests would relate to them many stories of the gods,

declaring that the events had occurred in their own city

in the time of the ancestors.

By following this

evolutionary tendency across the centuries, the

researcher can observe how the cosmic thunderbolt, a

centerpiece in innumerable tales of celestial combat,

emerged as the magical weapon of a legendary hero. It

became the sword, spear, hammer or club of a warrior who

continued to battle chaos monsters, but no longer in the

heavens. As a result of localization, the diminished

hero typically reveals an enigmatic mix of god and man,

as in the well known accounts of the Sumerian and

Babylonian hero Gilgamesh. Once reduced to human

dimensions, the hero could no longer hold onto his

original weapon, a weapon claimed to have shaken and

forever changed both heaven and earth.

Localization of

the celestial dramas recorded in earliest times had a

huge impact on Greek imagination. The best indication of

the evolutionary process is Greek epic literature,

including the most popular tale of all, Homer's Iliad.

Here the greatest of Greek heroes, the ideal warrior, is

Achilles. The hero's tale provided the fulcrum upon

which the poet integrated different tribal memories,

bringing together dozens of tribal heroes upon the

battlefields of a legendary, and entirely mythological

Trojan War. But the original themes, though subdued, are

still present.

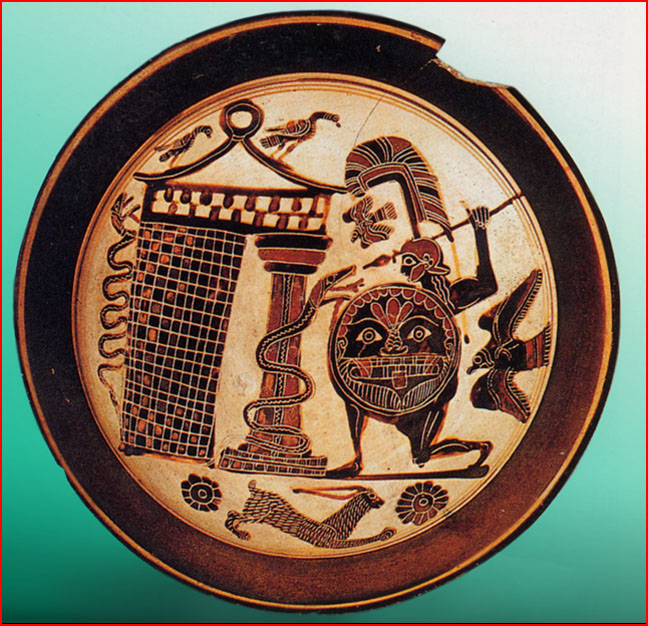

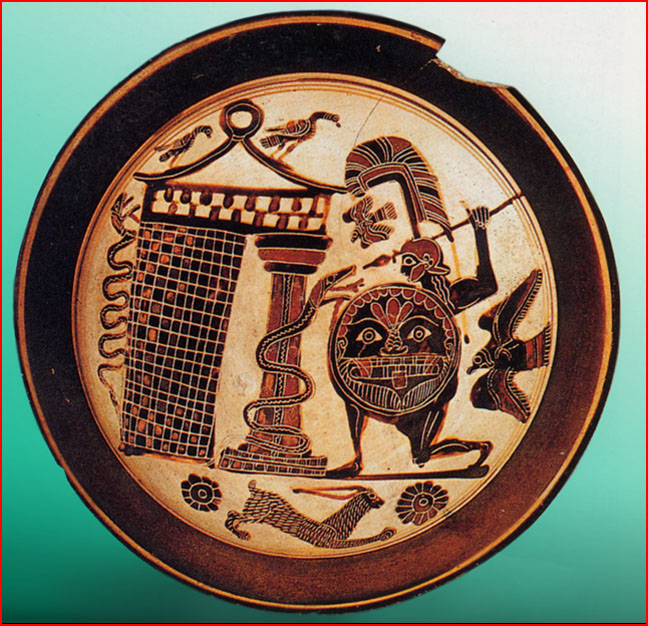

In the

illustration above, from a Greek drinking vessel, we

observe Achilles confronting the serpent-guardian of a

Trojan fountain. What is the relationship of this image

to the archaic contests between warrior gods and chaos

serpents?

Achilles' father

was the mythic king Peleus and his mother the "sea"

goddess Thetis, daughter of Oceanus, for whose

affections both Zeus and Poseidon had contended. Bathed

by his mother in the river Styx, the river that "joins

the earth and Hades", he was tutored by the Centaur

Chiron. His armor was fashioned by the god Hephaestus,

the very god who fashioned the thunderbolts of Zeus.

The actual

terrestrial city of Troy is the modern Hissarlik in

Turkey, the site of a fortified palace from the Bronze

Age onward. Neither this palace, nor anything uncovered

by archaeologists in the region could have inspired the

city of which the poets spoke! In the cultures of the

Near East and Mediterranean, hundreds of historic kings

left unmistakable proof of their lives and their

cultural influence. But of the countless kings,

warriors, princesses and seers in the Iliad, not one

finds historic validity. The reason for this is that the

claimed events did not occur on earth. The original

subject was a cosmic drama, whose episodes progressively

masqueraded as terrestrial history.

The similarities

shared by mythic heroes are vast, directing our

attention to ancient themes that can only appear

incomprehensible to the modern world. One overarching

theme is that of the hero's magical, and typically

invincible weapon. More than once the poets spoke of

Achilles' spear as forked, or possessing a "double

tongue", as when Aeschilos, in his Nereids, writes, "The

shaft, the shaft, with its double tongue, will come".

Practically speaking, a forked spear-point would have

doomed an ancient warrior. But the image was not rooted

in practical considerations. It comes directly from the

well documented form of the thunderbolt wielded by Zeus.

Of Achilles' spear, the poet Lesches of Lesbos (author

of the Little Iliad), wrote:

"The ring of gold flashed lightning round, and o'er

it the forked

blade".

It is only to be

expected that modern readers would see in these words a

simple poetic simile. But is there something more? The

answer must come through cross cultural comparison, for

the warrior bearing the thunderbolt in battle was indeed

a global theme.

Mystery of the Cosmic Thunderbolt(1)

Mystery of the Cosmic Thunderbolt(2)

Mystery of the Cosmic Thunderbolt(3)

Mystery of the Cosmic Thunderbolt(4) |